The term relevant negatives gets trotted out a fair bit. It should, as judicious use of actually relevant negatives is a crucial part of a quality report or oral description of a case. The problem is often the negatives given are irrelevant, or in some cases not only irrelevant but also imply that the speaker has no idea what he or she is talking about.

So what exactly is a relevant negative?

The “negative” component is fairly easy although there is confusion here also. A negative is the absence of a specific finding. It is not the same as a statement of normality. In other words “No hydrocephalus” is a negative. “Ventricles are of normal caliber” is not. The difference is important, as the use of a negative implies that a particular finding is specifically being sought and has not been found.

Now for the tricky bit; what does the “relevant” mean? Relevant to what? This is where most candidates get hopelessly confused and start muddying the waters by introducing irrelevant negatives. A relevant negative is the absence of a finding which would help in narrowing the differential diagnosis or would be important in management of the patient.

Crafting good relevant negatives

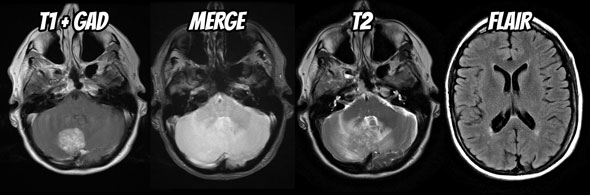

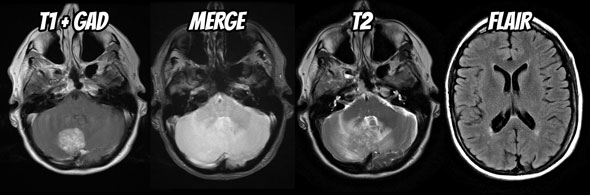

This is most easily explained with an example. Take the following posterior fossa mass (full case can be viewed here) and let's work out what are the relevant negatives are.

The trick is to first work out what the differential diagnosis for it is. Fortunately for this mass in a 60 year old female the likely differential is quite short: metastasis (common primaries include breast, lung, melanoma, RCC and GIT), hemangioblastoma and possibly a meningioma. We are not going to even consider an acoustic schwannoma or epidermoid as these are easily excluded by location and appearance.

Additionally as the patient is 60 years of age first presentation of von Hippel Lindau syndrome would be unusual, and it is probably safe to not dwell on it too much, lest you give the impression you do not know this.

Next you need to know which features are going to help you distinguish between them. They include:

- large flow voids are common in hemangioblastomas

- hemorrhage is common is RCC and melanoma metastases

- broad dural base / dural tail are common in meningiomas (although can be seen in dural metastases e.g. breast cancer)

- multiple lesions would favor metastases, or hemangioblastoma in the setting of von Hippel Lindau syndrome (unlikely in this age group).

You also need to think about management issues, the main one in this case is distortion of the fourth ventricle.

Relevant negatives in action

So here is how I would try and present his case. Relevant negatives are in bold.

- Within the right cerebellar hemisphere is a rounded vividly enhancing mass with surrounding vasogenic edema. It exerts significant local mass effect, distorting the fourth ventricle but at this stage is not associated with obstructive hydrocephalus. The mass does not abut the dura, appearing intra-axial. It does not have prominent flow voids nor is there evidence of hemorrhage. No other similar lesions are seen either in the posterior fossa or elsewhere.

Then you can throw in some statements of normality if you really feel like it, although in this instance you have covered most things. You could go on and add:

- The remainder of the scan is unremarkable for age.

Your next step would be your conclusion (or interpretation) and your reader / examiner won’t be at all surprised when you state:

- Findings in this patient favor a solitary metastasis, and a lung or breast primary are most likely.

You don’t even need to go into why at this stage, because you have, by virtue of your description and judicious use of relevant negatives, already implied that you know the differential diagnosis and the important features of each.

It is important to note that sometimes a relevant negative does not preclude discussing a particular aspect of the case, and it would be prudent in this case to also add:

- Despite no current obstructive hydrocephalus, urgent referral to a neurosurgeon is prudent and I would contact the treating physician to inform them of these findings.

Why is this so often done badly?

The problem with using relevant negatives well in the setting of an oral exam is that it requires you to have a differential very early on in the case, before you have described andy very much. This is usually the case by the time you get to your exam, but is usually not the case when you are starting out. So if have not been effectively practicing without wasting time or practicing your oral technique in the shower from the very start, you will not have been practicing the secret art of relevant negatives. The end result is that your descriptions will be longer, baggier, filled with seemingly random negatives and your examiner will be unsure of what you are going to say in your conclusion.

So, go back and practice. Look at your reports and the way you present cases and look for ways of introducing relevant negatives and removing irrelevant ones. This will have an enormous impact on how well you convey knowledge during an oral exam (see islands of knowledge vs puddles of ignorance) as well as allow you to create well crafted reports for the rest of your professional career.

Read next: Never surprise your examiner

Dr Frank Gaillard is a neuroradiologist at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, Melbourne, Australia, and is the Founder and Editor of Radiopaedia.org.

NB: Opinions expressed are those of the author alone, and are not those of his employer, or of Radiopaedia.org.

Dr Rene Pfleger is a radiology registrar at Aalborg University Hospital, Denmark.

Dr Rene Pfleger is a radiology registrar at Aalborg University Hospital, Denmark.

Every month or two we will collate some of the feedback we get from our users and post it on this blog. It is always rewarding to hear that what we are building is important and appreciated. If you have feedback or a story of how Radiopaedia.org helps you, please send it to

Every month or two we will collate some of the feedback we get from our users and post it on this blog. It is always rewarding to hear that what we are building is important and appreciated. If you have feedback or a story of how Radiopaedia.org helps you, please send it to

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.