Recently, following a case of a child who swallowed a pendant of a popular cartoon character (case here), a small flurry of media attention has been focused on Radiopaedia.org. Although some articles, including this one from ABC news in Australia, took the time to understand what we are about, many merely latched on to the more whimsical side of radiology.

Yes it is true we have a modest collection of rectal foreign bodies. Yes, they are a source of amusement; I would be lying if I didn't admit that I find the idea of someone presenting to the emergency department with an aubergine tucked up where the sun-don't-shine just a little bit funny.

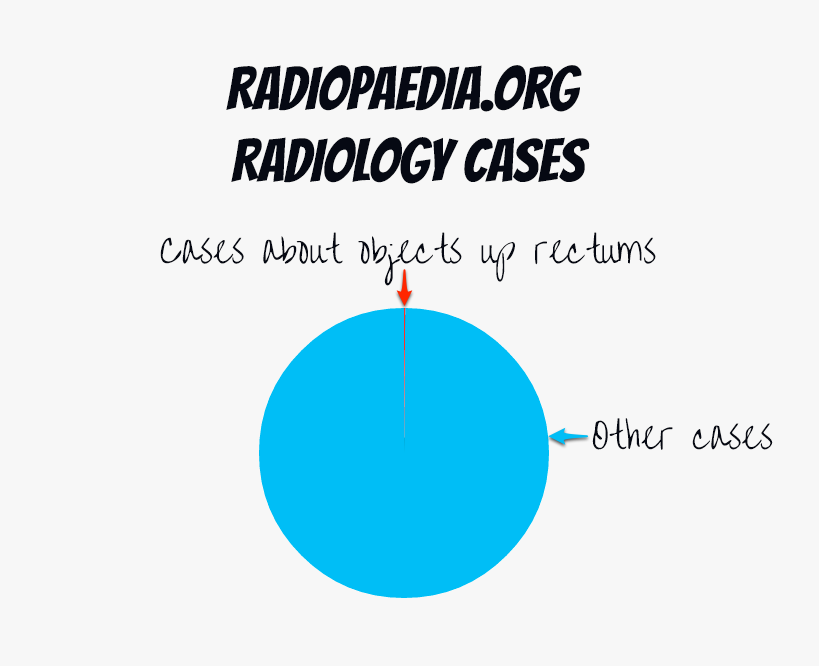

These cases, however, represent a tiny fraction of our collection (~0.1% of cases and ~0.001% of images on the site; most of our 17000+ cases are detailed with multiple modalities and each comprise hundreds of images, description of the findings, and associated test results, e.g. biopsy results etc...). They are, therefore, at most a footnote to what we are about: building the most comprehensive, reliable and accessible radiology resource ever, to enable clinicians from every corner of the world to better diagnose and treat their patients.

We believe that by sharing our collective knowledge, without imposing restrictions based on one's personal, institutional or geographical wealth, we can do a great deal of good. Over the past almost 10 years, we have made great progress, with our site now visited by around 2 million individuals every month, from every country on earth. The vast majority of these visits, well over 99%, are to non-sensational, detailed technical pages covering almost every topic in radiology. Many of the conditions we discuss are common but we also have many examples of very rare conditions; the sort of condition a radiologist may only ever see one example of during their career. By providing a platform where we can share such cases with our colleagues, we help each other make the right diagnosis, and in turn help our clinicians treat these patients better.

So while we appreciate media attention, it would be great to not lose track of the real goal of Radiopaedia.org.

Frank

|

Dr Frank Gaillard is a neuroradiologist at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, Melbourne, Australia, and is the Founder and Editor of Radiopaedia.org. NB: Opinions expressed are those of the author alone, and are not necessarily those of his employer. In this case they are very much the opinons of Radiopaedia.org. |

Teapot syndrome with grade 4 acrofemoral synostosis

Teapot syndrome with grade 4 acrofemoral synostosis

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.