Kernicterus, also known as chronic bilirubin encephalopathy, describes the chronic, toxic, permanent sequelae of high levels of unconjugated bilirubin on the central nervous system of infants. It is part of the spectrum of bilirubin-induced neurologic dysfunction, which also includes acute bilirubin encephalopathy.

On this page:

Epidemiology

Kernicterus is thought to be very rare and decreasing in incidence, although the exact incidence is unknown 1,2.

Clinical presentation

Kernicterus is clinically characterised by chronic and permanent neurological manifestations in the infant, including 1:

choreoathetoid cerebral palsy

cranial neuropathies, e.g. causing sensorineural hearing loss or gaze palsies

ataxia

intellectual disability

dental dysplasia

Nearly all affected infants will have clinical features of acute bilirubin encephalopathy, such as jaundice, somnolence, hypertonia, opisthotonos, and retrocollis, prior to manifestation of these permanent neurological signs 1. These early signs are often unfortunately mistaken for mimics such as sepsis or hypoglycaemia 1.

Very rarely, kernicterus can manifest in adults, although evidence for this appear only in infrequent case reports 3. Interestingly, the condition can also manifest in animals 4.

Pathology

Unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia is the aetiology of kernicterus, especially when total bilirubin levels exceed 35 mg/dL 1,2,5. Unconjugated bilirubin, or ‘free bilirubin’, can cross the immature blood-brain barrier when the concentration exceeds the normal albumin binding capacity and normal conjugating capacity of the liver 1,5. In adults, this is less likely to occur due to the matured blood-brain barrier, and only occurs when this barrier is damaged or impaired in some way 3.

As a result, this unconjugated bilirubin deposits symmetrically in the brain, with a predilection for the globus pallidi, subthalamic nuclei, hippocampus (especially CA2-CA3), putamen, thalamus, and cranial nerve nuclei (especially of CN III, IV, and VI) 1,2,5-10. Macroscopically, these areas have a characteristic yellow appearance 1,2,5-10.

Although the reasons for deposition causing neurotoxicity are not well understood, one theory is that once deposited, unconjugated bilirubin inhibits astrocyte uptake of glutamine which leads to overstimulation of neurones and eventual neuronal death, causing permanent neurological features 11.

Aetiology

There are numerous underlying causes for unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia, and thus kernicterus, in infancy 1-3,5-10:

haemolysis (e.g. glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, ABO or Rh incompatibility)

sepsis

disorders of hepatic bilirubin metabolism (e.g. Crigler-Najjar syndrome)

acquired defects in bilirubin conjugation (e.g. Lucey-Driscoll syndrome)

bruising from birth trauma

prolonged breast milk jaundice

Importantly, causes of conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia are not implicated in kernicterus.

Radiographic features

MRI

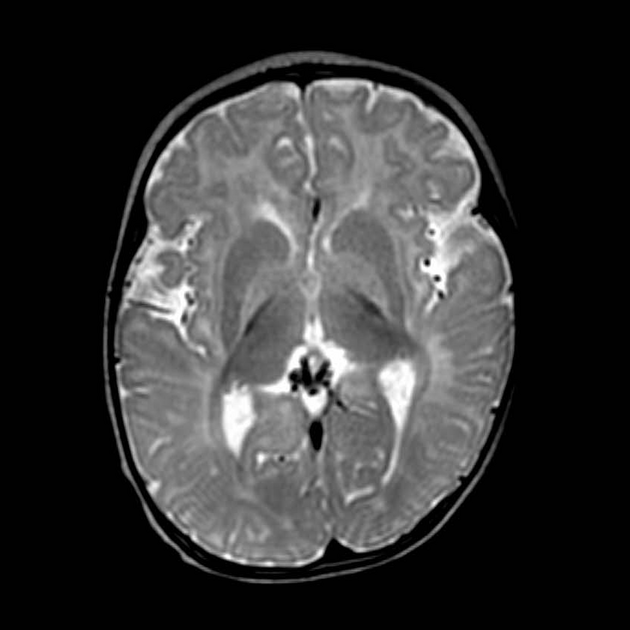

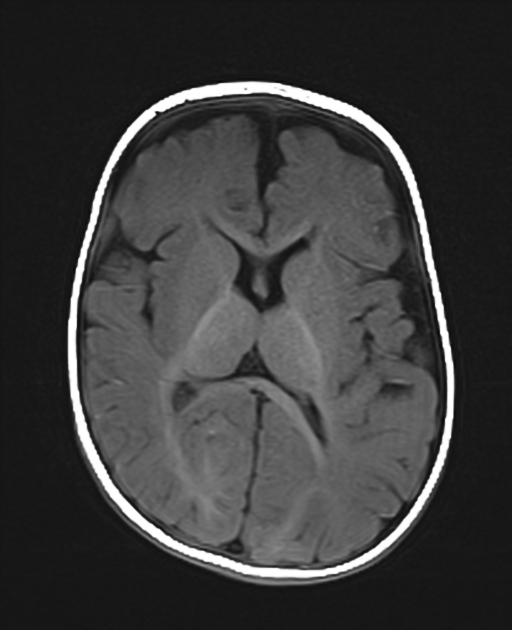

MRI is the imaging modality of choice, and typically reveals signal abnormalities in areas that correspond to pathological deposition of unconjugated bilirubin 6-10. Of those aforementioned areas, the posteromedial borders of the globus pallidi seem to be the most sensitive region of the brain in detecting signal anomalies associated with kernicterus 8. These signal anomalies are characteristically:

T1: these regions have variable signal abnormalities, typically appearing hyperintense initially but eventually evolving to hypointense 6-10,12

T2: although may be initially normal, these regions develop high signal intensity as the disease progresses 7-10

DWI: normal 9

MR spectroscopy has been infrequently reported in the literature in regards to kernicterus, however existing studies have reported increased levels of glutamine and glutamate along with decreased levels of choline and N-acetyl-aspartate 9.

Treatment and prognosis

There is no disease-modifying treatment available, and prognosis is poor 1,2,6. Early management of neonatal hyperbilirubinaemia, with therapies such as phototherapy and exchange transfusions, should be employed to prevent kernicterus 1,2,6.

History and etymology

Kernicterus was first described by Christian Georg Schmorl (1861-1932), a German pathologist, in 1904 13. The name stems from the German kern (“nucleus”) and ikterus (“jaundice”).

Differential diagnosis

encephalitis

various inborn errors of metabolism

various degenerative diseases

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.