Low back pain, lumbar or lumbosacral pain is an extremely common clinical symptom and the most common musculoskeletal condition affecting the quality of life that can be found in all age groups. It represents the leading cause of disability worldwide 1-3.

On this page:

Epidemiology

Low back pain is a very common symptom worldwide 1-4 with more than 80% of adults experiencing low back pain at some point in their life 2. It is more prevalent in low and middle-income countries with a global yearly prevalence of more than 30% 1 and up to 30% in higher-income countries such as the US 5. Women are more frequently affected 1. It occurs in all age groups being rare in the first decade, but up to 40% of teenagers have experienced back pain at some point 1. In the adult population, there is a temporary low in early adulthood with a steady increase thereafter to a peak in the seventh decade 1,2.

Risk factors

The following lifestyle factors have an increased risk of experiencing low back pain 1,2:

-

biophysical factors

alterations muscle in size, composition

alterations in coordination

-

psychological factors

self-efficacy

anxiety

avoidance beliefs

catastrophising

-

social factors

low socioeconomic status

lesser education

routine and manual occupations

high physical workloads

lesser work satisfaction

compensated work injury

-

lifestyle-related factors

-

comorbidities

Clinical presentation

Low back pain can be acute (<6 weeks), subacute (6-12 weeks) or chronic (>12 weeks) 2,3 and is defined by its location typically referred to as between the buttock and the lower ribs. Low back pain can be subdivided into the following conditions 5:

axial lumbosacral pain: pain to the lumbar and sacral spine

radicular pain: pain travelling into the lower extremity along a dermatome

referred pain: pain spreading into the hip, buttock or lower extremity in a non-dermatomal pattern

It can be associated with several other clinical complaints and symptoms 1 such as leg pain, numbness, weakness or decreased reflexes and other clinical scenarios or constellations 1.

Associated neurological symptoms, suspected extravertebral causes and “red flags” or other serious conditions might require immediate further diagnostic workups such as supplemental physical examination, laboratory tests, imaging or specialist referral depending on the suspected diagnosis 3.

Discogenic back pain is generally exacerbated by forward flexion, whereas facet joint pain is generally exacerbated by extension and rotation 10.

Pain severity might be estimated on measurement instruments such as the Visual Analogue Scale.

Red flags and yellow flags

red flags are somatic warning signs indicating specific spine-related diagnoses 3,4

yellow flags are psychosocial risk factors for the development of chronic persistent pain 3

Pathology

Low back pain is a symptom and not a disease that results from several pathologies 1. Low back pain is considered a complex condition with multiple contributing factors such as genetic, biophysical, psychological and social factors as well as comorbidities and pain-processing mechanisms 1.

Aetiology

In the vast majority of patients, no specific nociceptive cause can be found and only a smaller amount of cases can be attributed to a clear pathological cause such as the following 1,4,6:

-

mechanical causes

muscle strain/spasm (up to 70%)

-

degenerative disc disease (10-15%)

-

sacroiliac joint disease, e.g. sacroiliitis, osteoarthritis, instability (~15%) 9

~10% of patients will have sacroiliitis findings on CT 11

spondylolysis (<5%)

spinal canal stenosis (~3%)

facet joint osteoarthritis (no relationship between imaging findings and low back pain 1)

vertebral fractures (~4%)

-

non-mechanical causes (<1%)

spinal tumours and bone metastases (<1%)

axial spondyloarthritis (<0.3%)

spinal infections (0.01%)

-

extravertebral causes of low back pain (~2%)

abdominal and visceral processes (cholecystitis, pancreatitis)

vascular diseases (aortic aneurysm, acute aortic syndrome)

urologic causes (urinary tract infections, urolithiasis, perinephric abscess, renal tumours)

pelvic causes (prostatitis, endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease)

mental and psychosomatic disorders

Radiographic features

Low back pain does not necessarily correlate with imaging findings. Patients with acute or subacute low back and without clinical evidence of specific serious conditions (neurological symptoms, red flags or extravertebral causes) have been shown to have no improvement or difference in outcome after imaging and therefore imaging should be avoided in those patients 3,4.

In the presence of somatic warning signs “red flags” or no improvement after six weeks of conservative therapy appropriate imaging has been recommended with relation to the suspected diagnosis and the estimated degree of urgency 3-5.

Plain radiograph

Plain radiography is suitable to assess bony abnormalities or fractures 4.

CT

CT can nicely visualise lumbar and thoracolumbar fractures and for the assessment of spinal canal stenosis and degenerative disc disease in a setting where MRI cannot be done or is contraindicated.

MRI

MRI can depict soft tissue abnormalities and bone marrow changes 4.

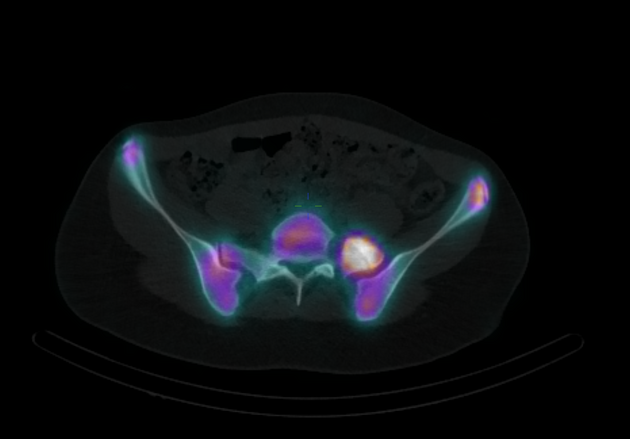

Nuclear medicine

Radionuclide scans can aid in the setting of suspected malignancy, spinal infection or axial spondyloarthropathies 6.

Treatment and prognosis

Nonspecific lower back pain has a mostly benign prognosis with approximately half of the patients recovering within the 6-12 weeks and only one-fifth taking a persisting disabling course 2,3. Chronic back pain has lesser chances of total recovery and no treatment that resolves the condition completely has been found 2,3 and therefore a multidisciplinary assessment should be strongly considered in cases of persistent pain and significant impairment of daily activities after 12 weeks 3.

Non-pharmacological measures including patient education, exercises, functional rehabilitation and manual therapy including massage and manipulation have been shown to improve quality of life 2-4.

Supportive pharmacotherapy including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or COX2-inhibitors might be indicated in situations of intolerable functional impairment or where it is potentially helpful in implementing patient activity 3,4. However, the pain medication should be halted or tapered off once pain improves 3. In this regard it is good to remember how the painful symptoms secondary to disc-radicular conflict for example, reveal a multifactorial genesis. In addition to the direct and indirect (or vascular-mediated) compression exerted by the herniated nucleus pulposus on the nerve root, pain finds its most important pathogenetic moment in the inflammatory state of the "connective" tissue 12.

Specific causes of lower back pain should be managed accordingly.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.