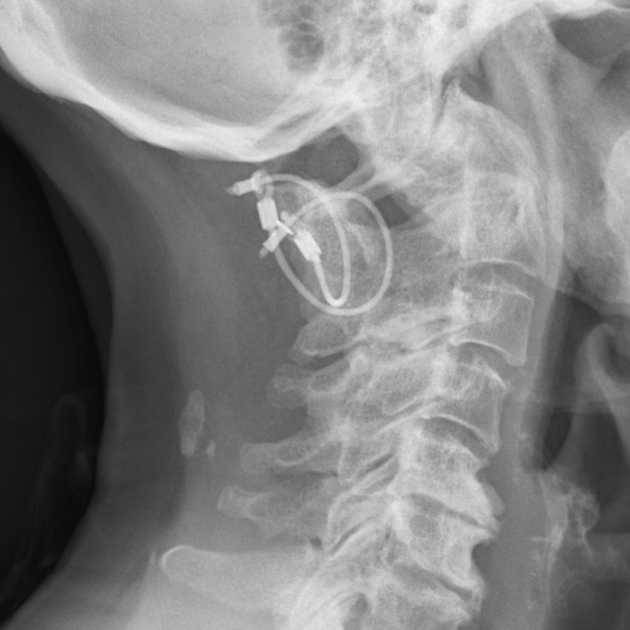

Posterior cervical fusion refers to a surgical spinal fusion technique of the cervical spine for conditions requiring posterior stabilisation. It might be done for the management of cervical spine fractures or combined with spinal decompression techniques such as laminectomy or laminotomy.

On this page:

History and etymology

The first posterior cervical fusion was performed in the late 19th century with bone graft as scaffolds and temporary external immobilisation 1-3 and the first posterior cervical fusion with a wire as hardware was reported by Hadra in the 1890s 2,3.

Indications

Posterior cervical fusion might be performed in the following situations 1,2:

- cervical spine trauma (hyperflexion injury)

- multilevel cervical spinal canal stenosis requiring posterior decompression

- spondylosis or degenerative disc disease resulting in myelopathy

- ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament

- diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

- ankylosing spondylitis

- cervical spinal instability

Procedure

The procedure and techniques and hardware used in the case of a posterior cervical fusion depend on the indication, location and the number of levels that need to be fused. A rough overview of the surgical procedure includes the following steps:

- longitudinal incision over the targeted levels

- exposure of the spinous processes and the posterior vertebral arches

- variably any necessary decompression procedures

- fixation and stabilisation of the vertebral arches at the involved levels

- variably bone graft insertion after decortication of facet joints

- suture of the interspinous and nuchal ligament as well as the subcutaneous tissue layer and the skin

Various techniques with different spinal instrumentation hardware include 1-5:

- spinal wiring

- sublaminar wiring

- interspinous wiring

- facet wiring

- posterior atlantoaxial fixation

- Gallie technique: wire cerclage connecting the C1 posterior arch with the C2 spinous process

- Brooks technique: two paired wires connecting the C1 posterior arch with the C2 laminae

- interlaminar clamps

- posterior cervical fixation systems

- plate-screw interfaces

- rod-screw interfaces

- screws

- pars screws (typically C2)

- lateral mass screws (C3-C6 and variably C7)

- pedicle screws (T1 and variably C2 and C7)

- laminar screws (possibility in C2)

- Magerl technique: transarticular screw fixation

Complications

Complications of posterior cervical fusion include complications of spinal surgery and the following 6,7:

- postoperative neurological deficits (e.g. C5 palsy)

- adjacent segment disease and junctional kyphosis

- failure of fusion/pseudoarthrosis

- dura leak/pseudomeningocele

- spinal infection

- spinal fracture

-

hardware malpositioning

- spinal cord injury

- nerve root injury

- injury to the vertebral artery

- loosening/periprosthetic osteolysis

- hardware failure

- implant migration

Radiographic features

CT

CT can be used to detect and characterise the location of implants as well as complications.

MRI

MRI can be used to evaluate the spinal canal in particular in the setting of suspected complications. Depending on the implanted hardware, MRI evaluation might be impaired by artifacts.

Radiology report

The postoperative radiological report should include a description of the following features:

- implanted hardware

- position of screws especially to the following structures

- spinal canal

- intervertebral foramen

- foramina transversarium

- bone grafts if present

- complications

Outcomes

Lateral mass screws can be used at multiple levels combined with rods and/or plates and feature a low complication rate, and better stability than wiring or translaminar screws. The use of cervical pedicle screws is technically more challenging, but offer potentially higher stability and a lower risk of screw back out. They have a higher risk of a spinal cord, nerve root or vertebral artery injury and are usually used at the T1 level and variably at C2 and C7 1,2.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.