Enterolithiasis represents the formation of dense concretions (enteroliths) within the gastrointestinal tract, typically as a consequence of intestinal stasis due to underlying pathology.

On this page:

Epidemiology

The condition is fairly common, with a reported prevalence of enterolithiasis ranging between 0.3-10% in the general population, largely due to widespread diverticular disease of the colon 1.

Clinical presentation

Symptoms are dominated by that of the causative condition, typically abdominal pain and cramps, nausea, vomiting are present 1.

Pathology

Stasis of bowel content due to any cause can result in the formation of these concretions. In primary enterolithiasis the stones are formed directly within the lumen of the bowel, whilst in secondary forms stones formed elsewhere (e.g. gallbladder) enter into the bowel lumen. Primary enteroliths are formed during bowel stasis from the contents of the bowel. Proximal small bowel enteroliths predominantly contain choleic acid, whilst distal small bowel stones are primarily made up by various calcium salts which are more likely to precipitate in an alkaline environment. Stones can be composed of iatrogenic substances (e.g. barium, antacids), ingested indigestible materials (e.g. hair) or in the colon can be made up entirely by faecal matter itself 1,2.

Typical causes of primary enterolithiasis are:

- intestinal diverticula (most commonly seen)

- surgical anastomoses

- blind intestinal pouches and loops (e.g. Billroth II and Roux-en-Y procedures)

- blind ending bowel structures (e.g. appendicoliths and stones within Meckel diverticula)

- incarcerated bowel hernia

- stasis due to bowel tumours

- adhesions

- stenosing/stricturing Crohn's disease

- intestinal tuberculosis

Gallstone ileus remains by far the most common form of secondary enterolithiasis.

Radiographic appearance

Plain radiograph

The visibility of the stone depends on its calcium content, choleic acid stones are thus almost always radiolucent 1. Calcium-rich stones typically demonstrate a radiodense rim and a relatively radiolucent core 2.

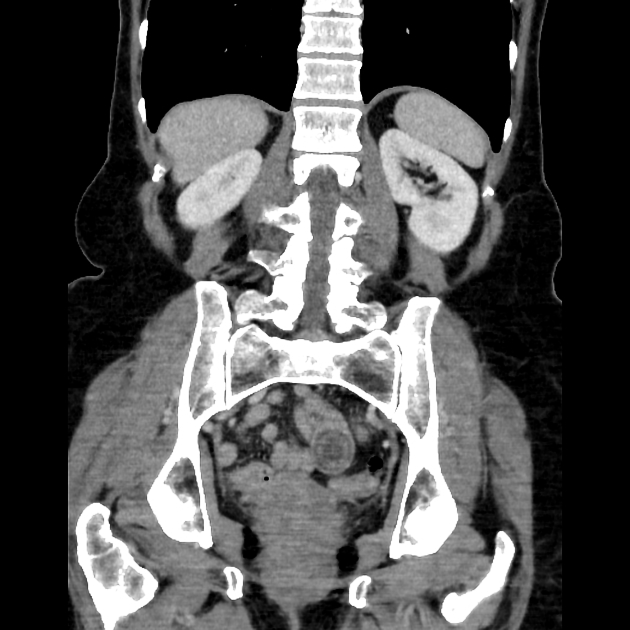

CT

More sensitive than plain film, however, caution is required as use of high-density oral contrast (e.g. diluted Gastrografin) can obscure radioopaque stones. In a typical scenario, CT is also better suited to assess the underlying condition and sequelae.

Treatment and prognosis

Enterolithiasis can result in severe complications such as bowel obstruction, intussusception, pressure ulceration of the intestinal mucosa and thus perforation, afferent loop syndrome, diverticulitis, intestinal haemorrhage and gangrene, or iron deficiency anaemia. Even in lieu of strictures/stenosis stones larger than 2.5 cm may cause intestinal obstruction. Depending on the degree of enterolith formation, and the size of the stones, and also depending on the underlying condition the management may be endoscopic or open surgical retrieval of the enteroliths and management of the causative condition 1.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.