Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a common cause of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). It is ‘atypical’ with regard to resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics, paucity of sputum, minimal leucocytosis and rarity of lobar consolidation 10.

On this page:

Epidemiology

M. pneumoniae is one of the most frequent causes of CAP in otherwise healthy adults until age 40 and is particularly common between the ages of 5 and 20 years accounting for around 40% of CAP 7 in this age-group.

Transmission is human to human by respiratory droplets induced by coughing and the incubation period is long, averaging 2-3 weeks. Up to 10% of those infected develop pneumonia. Outbreaks commonly occur in schools, colleges, hospitals, aged-care facilities and in closed populations such as military establishments or prisons. Epidemics may occur every 3-5 years. Lingering cough is typical and organisms continue to be excreted after clinical recovery. M. pneumoniae is also a frequent commensal in the respiratory tract.

Pathology

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a tiny parasitic bacterium in the class mollicutes (Latin for soft skin). They lack a cell wall, making them resistant to penicillins and invisible on Gram stain. M. pneumoniae causes upper and lower respiratory tract disease. It binds to ciliated epithelium preventing ciliary clearance. Hydrogen peroxide production causes oxidative damage and apoptosis. Pneumonia severity depends on the maturity of the host immune system.

Bronchitis and peribronchitis with interstitial thickening, alveolar filling and areas of atelectasis are typical, similar to other atypical pneumonias. Fatal pneumonia is rare and is associated with oedema, mucosal ulceration, haemorrhage, ARDS, thrombosis, DIC and multi-organ failure. Fulminant infection accounts for less than 0.5% of cases.

Community-acquired distress syndrome (CARDS) exotoxin is a unique virulence factor of M. pneumoniae.

Diagnosis

Confirmation of the diagnosis is helpful to track outbreaks or to investigate autoimmune complications such as haemolytic anaemia, myocarditis or encephalitis. DNA testing using nucleic acid amplification techniques (NAATs) and real-time PCR is rapid and reliable if there are sufficient organisms in the sample. A positive result can indicate active or recent infection or the presence of commensal or non-viable organisms.

Rising antibody titres indicate active infection in immune-competent hosts.

Culture is slow and challenging and generally not performed.

Cold agglutination is neither sensitive nor specific.

Clinical presentation

Following infection, non-productive cough slowly increases over a period of 2-3 weeks becoming incessant and persisting for weeks. Although spontaneous resolution is the rule, < 25% develop extrapulmonary invasion or autoimmune disease which can be severe 9.

Clinical features invariably include intractable cough and any of the following:

headache (typical)

low fever and chills (not rigors)

sore throat

“walking pneumonia” (ambulant despite pneumonia)

sickle-cell anaemia patients may suffer acute chest syndrome

arthralgia and myalgia, septic arthritis and osteomyelitis

dermatological complications, 25% (erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, ulcerative stomatitis, bullous exanthems)

Subclinical haematological disease may affect < 50%:

autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (especially children)

CNS 11 invasion is relatively common and is usually delayed by about 10 days, however in 20% respiratory disease may be absent:

encephalitis - most common in children

cerebral arteriovenous occlusion and infarction

Cardiac disease is uncommon and generally affects adults:

Abdominal disease:

nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea

acute renal failure (glomerulonephritis or fulminant haemolysis)

Radiographic features

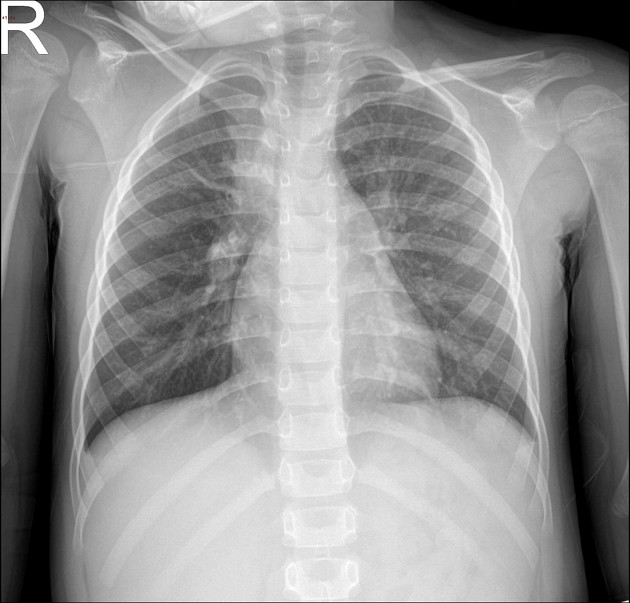

Plain radiograph

Radiographic findings may be greater than expected from the clinical features and commonly include uni- or bilateral lower lobe or perihilar bronchopneumonia with reticulonodular opacity, bronchial cuffing and linear atelectasis. Lobar consolidation is rare but interstitial disease may cause confluent hazy opacity (pseudoconsolidation). Small effusions can be seen on lateral views or decubitus views in up to 20% and may indicate more severe disease. Empyema is rare. Hilar lymphadenopathy is uncommon 8.

CT

Described features include

centrilobular nodular and tree-in-bud pattern

peri-bronchial thickening

patchy distribution

hazy and ground glass opacities

lobular opacity

pseudoconsolidation due to interstitial disease

pleural effusion in 20% 8

Differential diagnosis

Viral and other atypical pneumonias such as Chlamydia pneumonia which cause a bronchitis/bronchopneumonia pattern. Hilar lymphadenopathy with patchy lung opacity could mimic TB.

Treatment and prognosis

Most patients recover well without antibiotics. Patients with serious complications, patients with immune-deficiency and those with sickle cell disease should be treated.

Macrolides such as azithromycin and clarithromycin are generally effective and are preferred in children due to lower toxicity. Resistance is known to occur.

Tetracyclines are indicated for central nervous system involvement. Fluoroquinolones are bactericidal and therefore advantageous for immunocompromised patients and systemic infection.

Immunity is short-lived and reinfection is possible.

A small proportion of patients may develop abscess, necrotising pneumonia, fibrosis, bronchiectasis, bronchiolitis obliterans, ARDS, respiratory failure and extrapulmonary complications.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.