Oesophageal varices describe dilated submucosal veins of the oesophagus, and are an important portosystemic collateral pathway. They are considered distinct from gastric varices, which are less common.

On this page:

Epidemiology

Oesophageal varices are present in ~50% of patients with portal hypertension 1,2. They occur in greater frequency in patients with more severe cirrhosis, for example oesophageal varices may be present in ~40% of patients with Child-Pugh A cirrhosis, but in ~85% of patients with Child-Pugh C cirrhosis 1,2.

Clinical presentation

Patients will generally be asymptomatic until a variceal haemorrhage, which occur at a yearly rate of 5-15% 1,2. In the case of a variceal bleed, patients will usually present with stigmata of upper gastrointestinal bleeding; haematemesis, melaena, presyncope and syncope, and progression to hypovolaemic shock 1,2. The primary predictor of variceal bleed is variceal wall tension, which is a metric that encompasses vessel diameter (larger is worse) and pressure (higher is worse) 1,2.

Additionally, patients will often have stigmata of portal hypertension and cirrhosis – the most common aetiological basis for oesophageal varices.

Pathology

Two types of oesophageal varices have been described.

-

uphill oesophageal varices

most common form 1-4

-

typically caused by portal hypertension, as a collateral pathway between the portal vein and the superior vena cava (via the azygos vein) 1,2

the most common cause of this phenomenon is cirrhosis secondary to alcohol excess 1-4, however less common aetiologies include primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, portal vein thrombosis, Budd-Chiari syndrome, and schistosomiasis 5

typically present in the lower third of the oesophagus 1-4

-

commonly co-occur with gastric varices, which have an identical pathophysiology, but are notably less common 1,2

when co-occurring, most commonly there is extension of the oesophageal varices along the lesser curvature of the stomach (type GOV1 in the Sarin classification) 1

may be associated with paraoesophageal varices, which are varices of the adventitial oesophageal veins, and confer a low bleeding risk 6,7

-

relatively rare 3,4

typically caused by superior vena cava obstruction, as part of superior vena cava syndrome, as a collateral pathway between the superior vena cava into the portal circulation and/or the inferior vena cava 3,4

typically present in the upper third of the oesophagus, although can span the entire oesophagus if the superior vena cava obstruction is proximal to the inflow of the azygos vein 3,4

do not co-occur with gastric varices due to a different pathophysiological basis 3,4

have a relatively lower bleeding risk 3,4

Radiographic features

The gold-standard investigation for the evaluation of oesophageal varices is oesophagogastroduodenoscopy, however radiographic investigations may serve as a useful adjunct.

Plain radiograph

Oesophageal varices may be visible on plain radiograph if they are large. In such instances, they will have a non-specific appearance of a mass in the posterior mediastinum 8.

Fluoroscopy

Barium swallow may reveal longitudinal oesophageal luminal filling defects, representing oesophageal varices 6.

CT/MRI

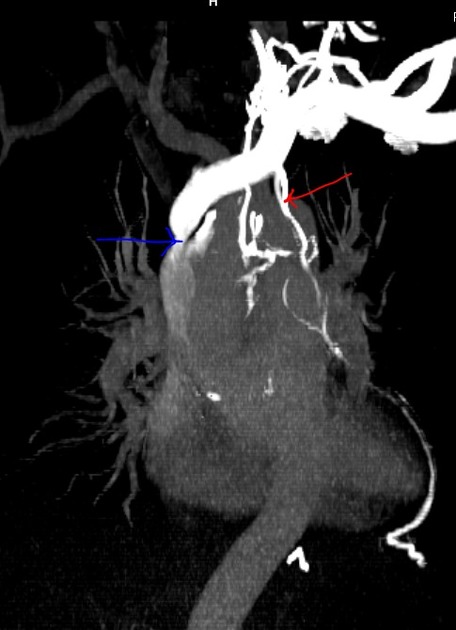

Oesophageal and paraoesophageal varices are readily visible on contrast-enhanced cross-sectional imaging, as torturous, enlarged, smooth enhancing tubular structures 6,9. They, depending on size and pressure, may protrude into the oesophageal lumen 6,9. In association, the oesophageal wall is also often thickened 6,9.

Angiography (DSA)

Digital subtraction angiography can also be a useful imaging modality in the assessment of oesophageal and paraoesophageal varices, providing direct visualisation through catheterisation and contrast injection of the left gastric vein 6,10. However, smaller varices are often not appreciated 6,10.

Treatment and prognosis

The mainstay of management for uphill oesophageal varices is primary prevention, which can be pharmacological (typically with non-selective beta-blockers), or with invasive endoscopic variceal ligation 1,2,11. The decision between pharmacological or endoscopic prevention is rather complex, and depends on factors such as variceal size and severity of cirrhosis 1,2,11. In patients with a prior variceal haemorrhage, the focus of management is secondary prevention, which can again be pharmacological (typically with non-selective beta-blockers), with invasive endoscopic variceal ligation, or through surgical creation of a portosystemic shunt (e.g. transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt) 1,2,11.

In the event of acute variceal haemorrhage, management includes resuscitation with intravenous fluids and blood products, administration of vasoactive drugs (such as terlipressin or octreotide), intravenous antibiotics, and endoscopic ligation 1. In severe cases refractory to standard management, salvage therapy with an oesophageal balloon tamponade device (e.g. Sengstaken-Blakemore, Minnesota tube) can be attempted 11.

The management of downhill oesophageal varices is quite different, and the focus is on treating the cause of the superior vena cava obstruction 3,4. Unlike uphill oesophageal varices, beta-blockade may not be useful. Endoscopic variceal ligation or banding, however, may be appropriate 3,4.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.