Ruptured saccular (berry) aneurysms usually result in subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) but can, depending on the location of the rupture and presence of adhesions to the aneurysm, also result in cerebral haematoma, subdural haematoma, and/or intraventricular haemorrhage.

On this page:

Epidemiology

Saccuar aneurysms form 97% of all aneurysms of the central nervous system. Up to 80% of patients with a spontaneous subarachnoid haemorrhage have ruptured an aneurysm and 90% of these aneurysms are located in the anterior circulation (carotid system), with 10% found in the posterior circulation (vertebrobasilar system).

Clinical presentation

Rupture of a saccular aneurysm with associated subarachnoid haemorrhage most frequently presents with a sudden, excruciating headache often described as "the worst I've ever had" or "thunderclap", resulting from blood being forced into the subarachnoid space under arterial pressure. Other features include:

visual changes

facial pain

seizures

autonomic disturbances (nausea/vomiting, chills and palpitations)

focal neurology (sensory loss, weakness, memory loss, language difficulties)

Examination findings include meningism (nuchal rigidity, fever, photophobia), altered consciousness, and other focal neurological signs such as ophthalmoplegia and pupillary abnormalities.

Pathology

Although some of the details of the pathophysiology of the formation of a saccular aneurysm remain unknown, the vast majority of aneurysms arise at arterial branching points along the circle of Willis 5. It is likely that the difference in composition of intracranial arteries compared to similarly sized arteries in the rest of the body (e.g. reduced thickness of adventitia) plays a significant role in aneurysm formation and rupture. Additional deficiencies in arterial wall strength (e.g. connective tissue disease or infection) further increase the incidence of aneurysm formation.

The rupture of a saccular aneurysm is in most cases spontaneous with no clear precipitant. In approximately one-third of cases, associated increased intracranial arterial pressure can be surmised by history or examination at the time of presentation (e.g. coital rupture, recreational drugs, childbirth, etc.) 6.

Aetiology

Saccular aneurysms either form sporadically or secondary to a genetic predisposition:

-

sporadic (most common)

a genetic component may also be implicated as there is an increased incidence in first-degree relatives of affected patients

-

genetic

Macroscopic appearance

An unruptured aneurysm appears as a thin-walled, shiny red outpouching usually measuring a few milimeters to 3 cm in diameter. Rupture usually occurs at the apex of the sac 5.

Microscopic appearance

The arterial wall adjacent to the neck of the sac usually shows thickening of the intima and thinning out of the media as the neck is approached. The sac itself is usually made up of thickened intima with the adventitia of the parent artery surrounding the sac 5.

Radiographic features

Determining the site of rupture

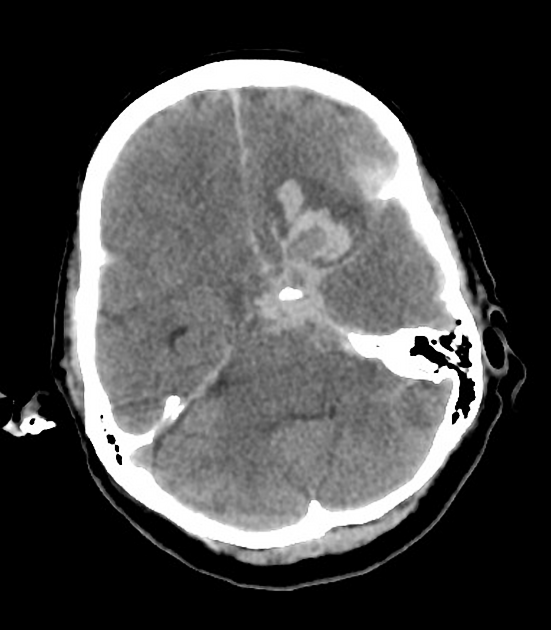

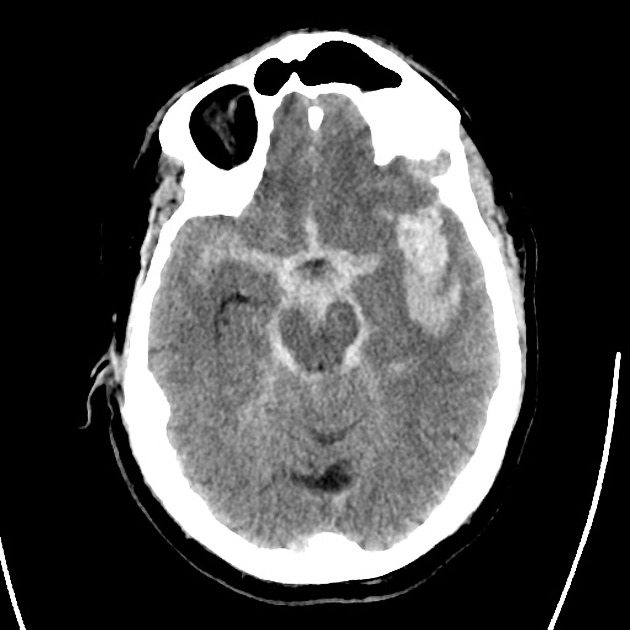

After rupture, the location of the blood or haematoma can help determine the site of the ruptured aneurysm in the majority of cases:

ACOM: (~35%) septum pellucidum, interhemispheric fissure and intraventricular, inferior frontal lobe (intraparenchymal)

PCOM: (~35%) Sylvian fissure, medial temporal lobe (intraparenchymal)

MCA: (~20%) Sylvian fissure and intraventricular, anterior temporal lobe (intraparenchymal)

basilar artery: (~5%) prepontine cistern

ICA: Sylvian fissure and intraventricular

pericallosal artery: corpus callosum

PICA: foramen magnum

An intracerebral haemorrhage adjacent to the ruptured aneurysm is known as a jet haematoma or flame haemorrhage, caused when an aneurysm abuts a lobe and at the time of rupture the pressure of the blood leaving the aneurysm dissects into the brain parenchyma. This often coexists with the presence of subdural haemorrhage from the aneurysmal rupture (which occurs in up to 8% of cases), although subdural haemorrhages can also occur independently due to saccular aneurysm rupture 7.

Aneurysmal characteristics suggestive of rupture

In cases of subarachnoid haemorrhage with multiple aneurysms, it is often important to identify which aneurysm has bled, as not all aneurysms present can be treated simultaneously. The location of blood, particularly if there is a parenchymal haematoma, is very helpful in identifying the responsible aneurysm. If this is not present or if blood is diffusely within the subarachnoid space, then aneurysm morphology can be helpful:

largest aneurysm

length-to-neck ratio >1.6 4

increased volume to surface area 4

aneurysm angulation 4

presence of a focal bleb/outpouching (known as Murphey's teat) 4

Treatment and prognosis

The rupture of an intracranial aneurysm is a medical emergency with a high mortality 3. Treatment focuses on managing both the aneurysm and complications of haemorrhage.

The aneurysm needs to be secured, either endovascularly by the introduction of coils and/or stents, or by surgery with clipping of the aneurysm neck.

Mortality from the first rupture is between 25-50% with repeat bleeding a common complication in survivors. With each recurrent bleed, the prognosis is worsened. In the first few days following a subarachnoid haemorrhage, there is an increased risk of additional ischaemic injury from the reactive vasospasm from surrounding vasculature 5.

Complications

Complications that require management include:

-

elevated intracranial pressure

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.