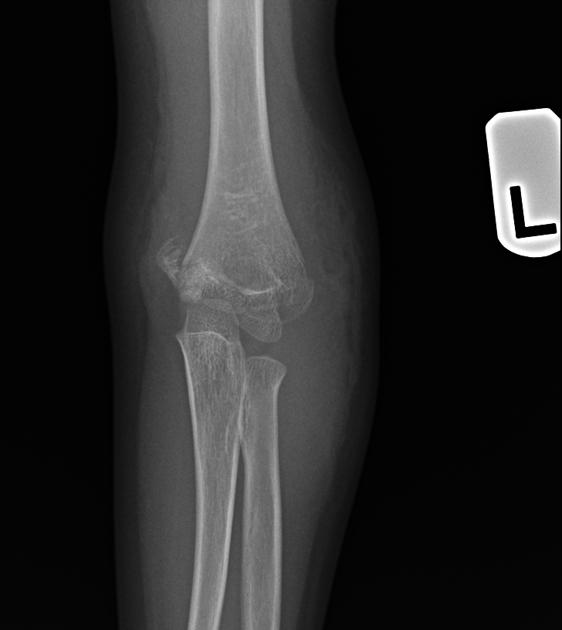

Supracondylar humeral fractures, often simply referred to as supracondylar fractures, are a classic paediatric injury which requires vigilance as imaging findings can be subtle.

On this page:

Epidemiology

Simple supracondylar fractures are typically seen in younger children, and are uncommon in adults; 90% are seen in children younger than 10 years of age, with a peak age of 5-7 years 4,6. These fractures are more commonly seen in boys 4 and are the most common elbow fractures in children (55-80%) 8.

These injuries are almost always due to accidental trauma, such as falling from a moderate height (bed/monkey-bars) 4.

Rarely (<5%) supracondylar fractures are seen due to a fall onto the flexed elbow. They occur in older individuals and require different management and are discussed separately: see flexion supracondylar fracture 5.

Mechanism

There are two types of supracondylar fractures: extension (95-98%) and flexion (<5%) types.

Extension type supracondylar fractures typically occur as a result of a fall on a hyper-extended elbow. When this occurs, the olecranon acts as a fulcrum after engaging in the olecranon fossa. The humerus fractures anteriorly initially and then posteriorly. They result in an extra-articular fracture line, and (when displaced) posterior displacement of the distal component.

Radiographic features

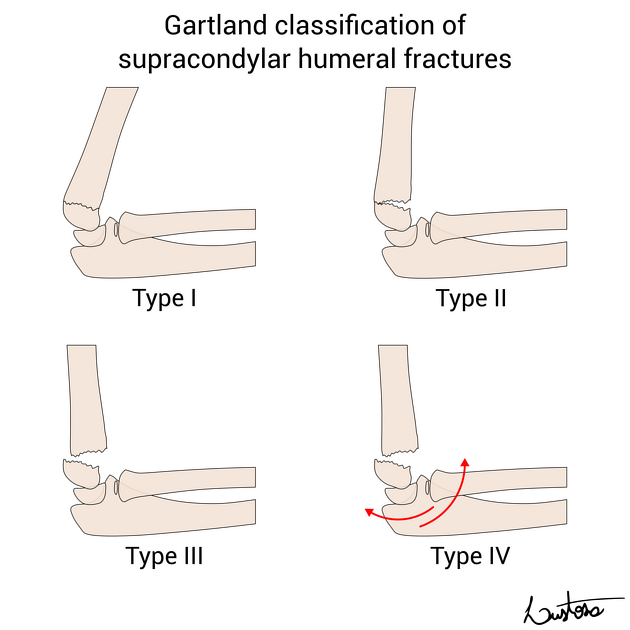

The Gartland classification is used to classify extension supracondylar humeral fractures into three types based on the degree and direction of displacement, and the presence of intact cortex 6,7,9:

-

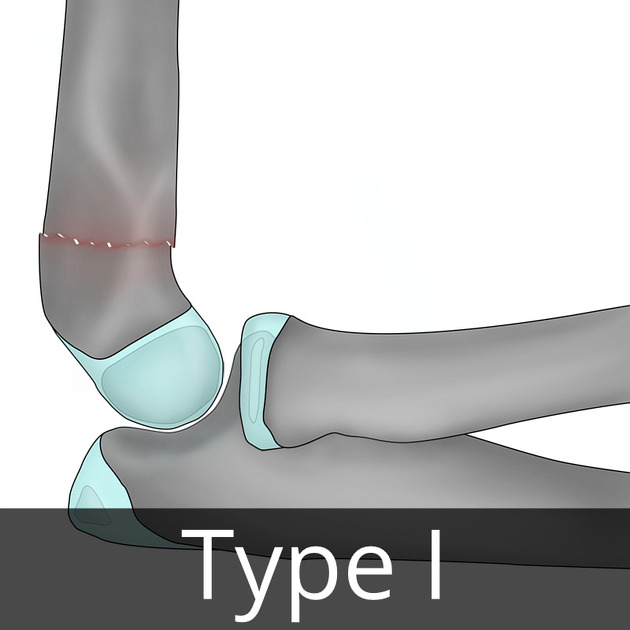

type I: undisplaced or minimal displacement(<2 mm)

Ia: undisplaced in both lateral and AP projections

Ib: minimal displacement, medial cortical buckle, capitellum remains intersected by the anterior humeral line

-

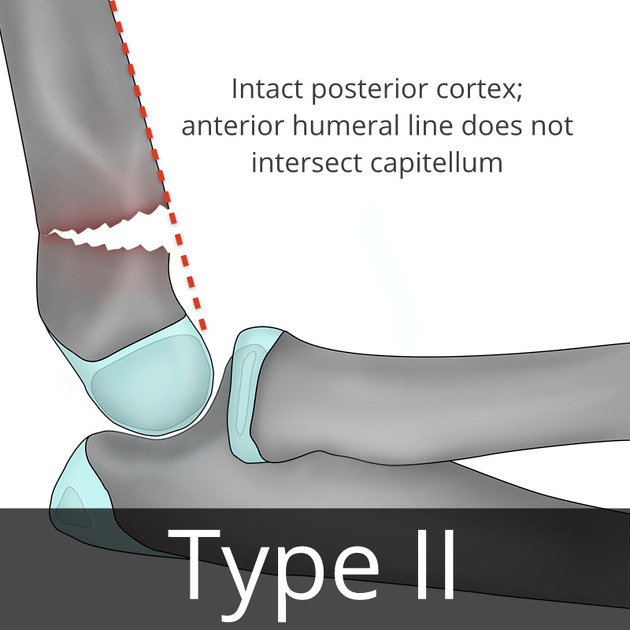

type II: displaced (>2 mm) with an intact, hinged posterior humeral cortex

IIa: no rotational deformity, with posterior angulation only. Anterior humeral line does not intersect capitellum

IIb: rotational or straight displacement but posterior humeral cortex remains in contact

-

type III: complete displacement

IIIa: complete posterior displacement with no cortical contact

IIIb: complete displacement with soft tissue gap (i.e. bone ends held apart by interposed soft tissues)

Since it was first described, a fourth Gartland type has been added that is diagnosed only intraoperatively. A supracondylar fracture is defined as Gartland type IV when it is displaced, with an incompetent periosteal hinge mechanism that leads to multidirectional instability in both flexion and extension 10.

Plain radiograph

Lateral and AP radiographs are usually sufficient, and in many instances demonstrate an obvious fracture. Often, however, no fracture line can be identified. In such cases assessing for indirect signs is essential:

anterior fat pad sign (sail sign): the anterior fat pad is elevated by a joint effusion and appears as a lucent triangle on the lateral projection

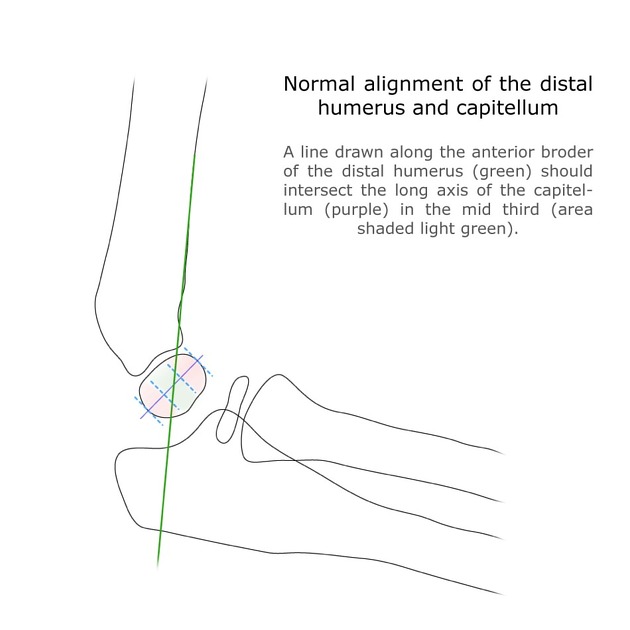

anterior humeral line should intersect the middle third of the capitellum in most children 2 although, in children under 4, the anterior humeral line may pass through the anterior third without injury

Radiology report

After ensuring that the films are technically adequate, assessment should include:

-

description of the fracture

location and especially presence of articular involvement

angulation (use the anterior humeral line)

alignment of the radius and ulna with the distal humerus

-

description of additional features

assess for joint effusion (anterior and posterior fat pad sign)

assess alignment of the radiocapitellar joint

remember to assess elbow centres of ossification (CRITOE)

Treatment and prognosis

Although in many cases the fracture is easily seen, in some instances all that may be seen is soft tissue swelling or an anterior fat pad sign. Even in the absence of an obvious fracture, the patient needs to be treated with a cast. Repeating radiographs after inflammation has subsided may be helpful in demonstrating the fracture; this is typically done 7-10 days later.

Management depends on the type and degree of angulation 5,7.

Type I

Type I (undisplaced) fractures are stable and can be treated with cast immobilisation for approximately 3 weeks.

Type II

Type IIa usually requires reduction (especially when angulation is more than 20 degrees). Although traditionally these fractures were treated non-operatively with cast immobilisation of the flexed arm to 120 degrees, this however dramatically increases the risk of ischaemic contracture (Volkmann contracture), as such most authors recommend percutaneous pinning (CRIF) and cast immobilisation with less than 90 degrees flexion 5,7. Type IIb always required reduction +/- fixation.

Type III

Type III fractures can sometimes be treated similarly to type II (closed reduction and percutaneous pinning, CRIF) although frequently the fracture is held open by interposed soft tissues requiring open reduction 7.

When K-wires are used they are generally used either from a lateral approach ( 2 or 3 wires) or as crossed pins (one wire medially, one wire laterally) 8.

Complications

There are three main complications 2,3:

malunion: resulting in cubitus varus (varus deformity of the elbow, also known as gunstock deformity)

ischaemic contracture (Volkmann contracture) due to damage/occlusion to the brachial artery and resulting in volar compartment syndrome

-

damage to the ulnar nerve, median nerve, or radial nerve

most commonly injured at the time of injury is the anterior interosseous nerve (AIN; a branch of the median nerve), followed by the radial nerve and then the ulnar nerve. Ulnar nerve injury is more common in flexion type fractures.

Most AIN, radial and ulnar nerve injuries resolve spontaneously without any intervention 8.

Osteonecrosis is a rare complication and is described as two types 9:

type A: lateral ossification centre osteonecrosis resulting in a defect in the apex of the trochlea resulting in a fishtail deformity

type B: entire trochlea +/- part of the metaphysis

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.