Vitreous haemorrhage refers to bleeding into the vitreous humour.

On this page:

Epidemiology

Vitreous haemorrhage has an incidence of approximately 7 in 100,000 1,2.

Clinical presentation

The most common clinical presentation is with sudden, painless visual loss to varying degrees of severity 2. Associated ‘floaters’ or shadows in the vision have also been reported 2. In traumatic cases, orbital pain may be present, although this is likely to be due to other orbital injuries rather than the vitreous haemorrhage itself 2.

Slit-lamp examination confirms the diagnosis through visualisation of blood in the vitreous chamber, although may have a limited role in detecting the underlying cause if the haemorrhage is diffuse 2.

Pathology

The vast majority of vitreous haemorrhage occurs secondary to proliferative diabetic retinopathy, posterior vitreous detachment, retinal detachment or tear (which in itself could be due to posterior vitreous detachment or proliferative diabetic retinopathy, among other causes), orbital trauma, or ocular malignancy 1,2,8. However, in a broader sense, bleeding into the vitreous chamber occurs through two main mechanisms:

rupture of normal vessels via mechanical forces: posterior vitreous detachment, retinal detachment or retinal tear, closed or open orbital trauma, non-accidental injury (shaken baby syndrome), Terson syndrome 1,2

pathological rupture of vessels: proliferative diabetic retinopathy, wet age-related macular degeneration, others causes of neovascularisation, ocular malignancy 1,2

Radiographic features

Ultrasound

Both A-scan and contact B-scan (more useful) ultrasound have a role in confirming the vitreous haemorrhage and also detecting underlying causes such as posterior vitreous detachment, retinal detachment or tear, trauma, or malignancy 1-3.

Findings with B-mode ultrasonography depend on both the severity of the haemorrhage and the time elapsed since the haemorrhage occurred 10:

-

acute vitreous haemorrhage

-

scattered, ill-defined collections of slightly echogenic opacities

often requires considerable increase in gain to visualise

demonstrate mobility with extraocular movements

-

-

subacute to chronic vitreous haemorrhage

-

organisation into more echogenic membranous structures 9

when severe may obliterate vitreous body as a confluent, echogenic haematoma

-

retains mobility with eye movements

mobility declines with age of haemorrhage

-

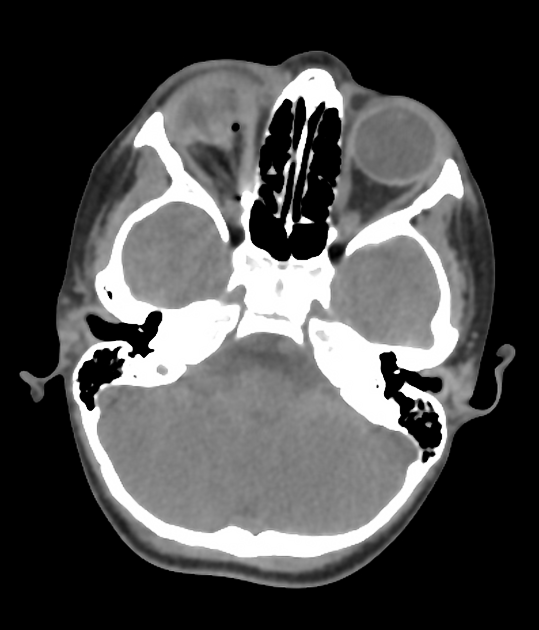

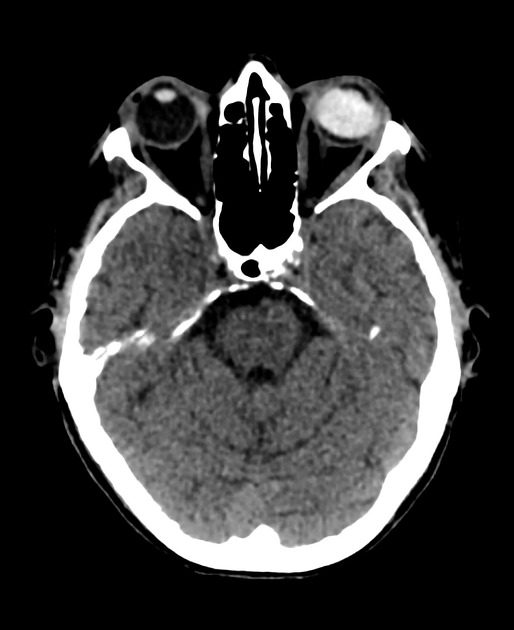

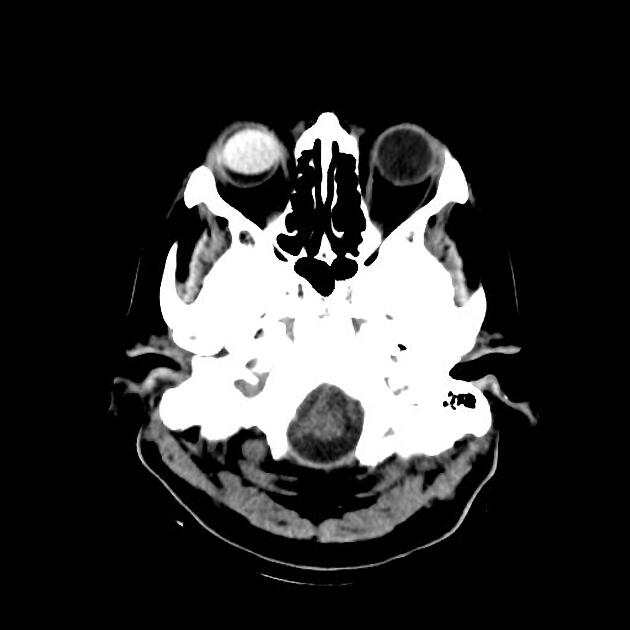

CT

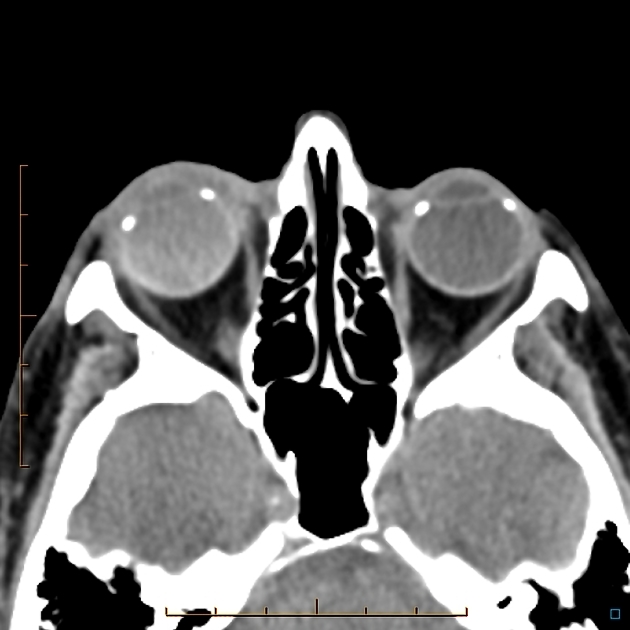

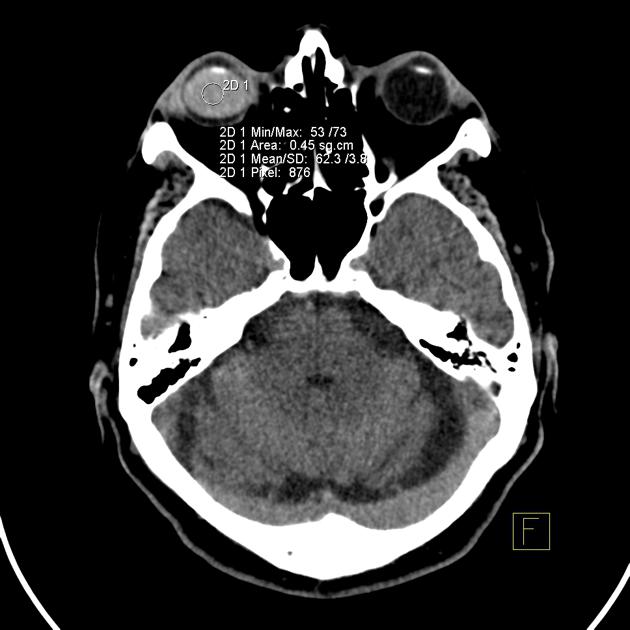

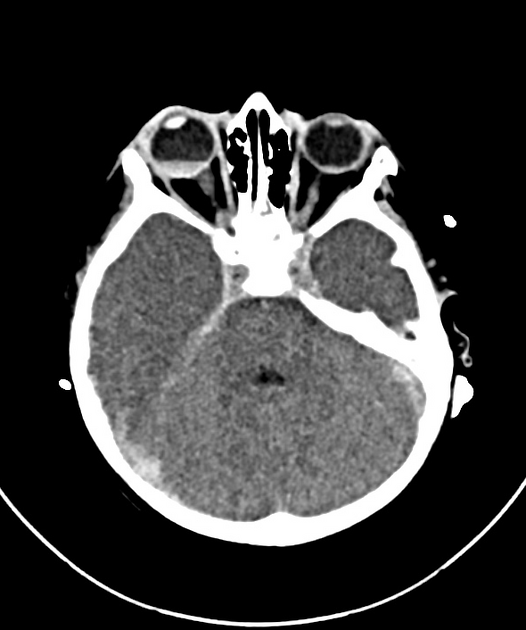

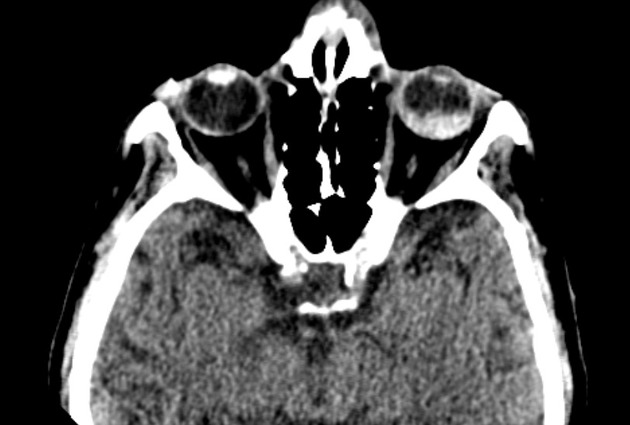

Haemorrhage usually demonstrates hyperattenuation, which may be either homogeneous or heterogeneous, in the vitreous chamber on CT 2,4-7. Similar to ultrasound, CT can also be utilised to detect underlying orbital pathologies, but has an advantage in also being able to detect extra-orbital pathologies such as subarachnoid haemorrhage (causing Terson syndrome) 2,4-7.

MRI

MRI is uncommonly performed but confirms findings seen on ultrasound and CT. Normally, the vitreous humour demonstrates T1 hypointensity and T2 hyperintensity 2,3,6,7. These normal signal characteristics are often not appreciated in cases of vitreous haemorrhage 2,3,6,7. The exact appearance of vitreous haemorrhage on MRI is very variable depending on the age of the blood (see ageing blood on MRI), however gradient-recalled echo or susceptibility-weighted imaging are considered the most useful and sensitive sequences where the haemorrhage will demonstrate low signal 2,3.

Treatment and prognosis

Although spontaneous regression of the haemorrhage is seen in approximately half of all patients, the condition may require operative intervention with posterior vitrectomy 2. Treatment of the underlying cause is also paramount 2.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.