Necrotizing fasciitis (rare plural: necrotizing fasciitides) refers to a rapidly progressive and often fatal aggressive necrotizing soft tissue infection primarily involving fascial planes and spreading hematogenously.

On this page:

Terminology

As fascia is variably defined, there can be confusion as to what this pathology truly constitutes. While anatomy texts often define superficial fascia as including the subcutaneous fat layer, the latest international nomenclature, Terminologia Anatomica, abandoned the term and most surgeons consider "fascia" to refer primarily to the deep (investing) fascia 3,10. Therefore, findings of infection in the subcutaneous tissue are usually considered part of cellulitis, while fasciitis is reserved for the involvement of the deep fascia 10. The term necrotizing deep soft tissue infection has been proposed as more encompassing than necrotizing fasciitis 20.

Epidemiology

Necrotizing fasciitis is relatively rare, although its prevalence is rising. Over the past few years there has been an increase in vibriosis due to warming coastal and estuarine waters off East Coast USA, Gulf of Mexico 22 and Australia 21. Vibriosis is a notifiable disease in the USA 22.

Risk factors

The most common risk factor is diabetes mellitus, especially in combination with peripheral arterial disease. Other predisposing factors include immunocompromise due to HIV infection, cancer, liver disease, alcohol use, or organ transplant.

Deep soft tissue infections can also occur in otherwise healthy individuals following surgery, penetrating trauma, minor wounds such as tattoos, piercings 22, insect bites or abrasions, or even blunt trauma with no clear portal of entry 7,15. Infections can enter wounds while bathing in warm coastal water or handling raw seafood. Bivalve filter-feeders such as oysters concentrate Vibrio species, especially if post-harvest temperature is too high 21. Coastal flooding exposes a larger population to infection 22.

Clinical presentation

The incubation period is short and is followed by acute painful inflammation and crepitus due to necrotizing skin and soft tissue infection, with or without hemorrhagic bullae. Infection spreads rapidly along the relatively hypovascular fascial planes and enters the bloodstream causing septicemia, fever and hypotension 15. Surgical findings include friable superficial fascia and foul grey "dishwater" exudate 15. Vibrio infections commonly cause gastrointestinal symptoms including diarrhea, stomach cramps, nausea and vomiting.

The Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) score is a robust screening tool that uses routine laboratory markers to evaluate the risk of necrotizing soft tissue infections, aiding in the clinical decision between operative management with debridement and conservative management with intravenous antibiotics. Regardless of LRINEC score, a high degree of clinical suspicion for necrotizing fasciitis should always prompt urgent surgical consultation and intervention 23.

Pathology

Microbiologically, there are two major recognized forms:

polymicrobial (type I): most common; involves both anaerobic and aerobic organisms, such as Clostridium, Bacteroides, and Peptostreptococcus in the former group, and Enterobacteriaceae family members and Staphylococcus aureus in the latter group 14

monomicrobial (type II): less common (10-15%); most commonly involves group A streptococci, the “flesh-eating bacteria” and may be complicated by toxic shock syndrome 3,4; less commonly due to Staphylococcus aureus and increasingly due to Vibrio species

The presence of anaerobes (or facultative anaerobes) in type I infection is responsible for the hallmark finding of gas formation found later in the course of polymicrobial necrotizing fasciitis. This finding is not present in monomicrobial necrotizing fasciitis due to group A streptococci.

Soft tissue infarction is seen in late disease with liquefaction of fat and muscle.

Location

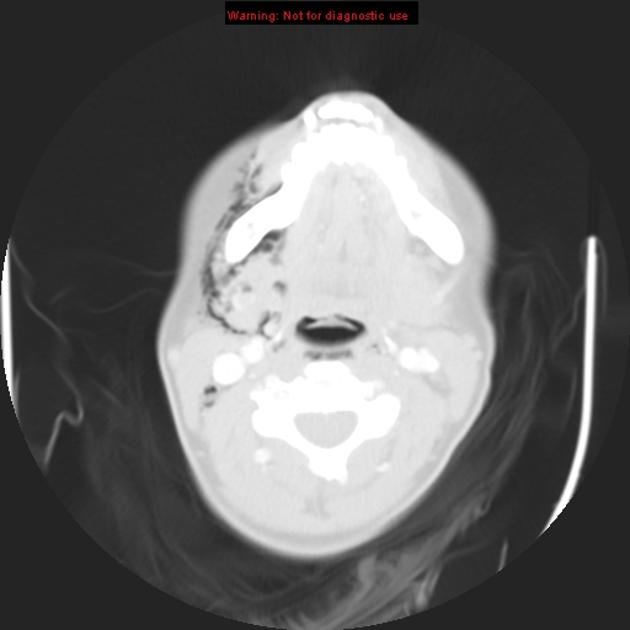

While necrotizing fasciitis can affect any part of the body, 50% of cases involve the lower extremities. Other common areas include the upper extremities, the perineum (Fournier gangrene), and the head and neck region 4,12. In neonates, the most common area involved is the trunk 15.

Radiographic features

Imaging plays a supportive role in diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis, as no imaging modality can exclude the diagnosis with certainty. A study with only non-specific evidence of soft tissue inflammation should not preclude or delay surgical exploration and intervention in cases with high clinical suspicion for necrotizing infection 20.

Imaging is more sensitive than physical exam for detecting the hallmark feature of soft tissue gas (subcutaneous emphysema) and can also identify findings contributing to infection such as foreign bodies 12.

Plain radiograph

Radiographs can be normal until the advanced stages of infection and necrosis. Early findings are non-specific, similar to those of cellulitis, such as increased soft-tissue thickness and opacity. Soft tissue gas is seen in only a minority of cases.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound may be more useful in children 4,10 (with a rising incidence after primary varicella infection 11). Sonographic findings include distorted and thickened fascial planes with turbid fluid accumulation in the fascial layers and subcutaneous edema. Soft tissue gas appears as a layer of echogenic foci with posterior dirty shadowing 12.

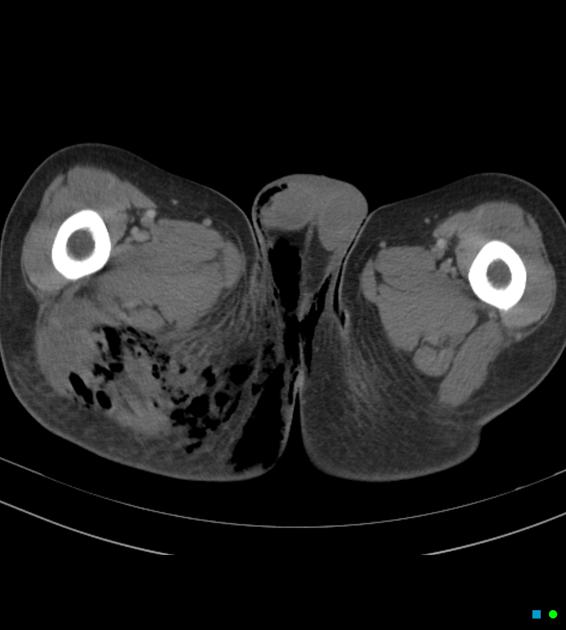

CT

CT is the most commonly used imaging modality for evaluation of suspected necrotizing fasciitis 12 owing to its speed and sensitivity for gas in the soft tissues, which is present in <50% of cases 20. The sensitivity of CT is 80%, but the specificity is low given overlapping features with non-necrotizing fasciitis 12. Gas within fluid collections tracking along fascial planes is the most specific finding but is not always present 12.

Other, non-specific findings include:

asymmetrical fascial thickening associated with fat stranding

edema extending into the intermuscular septa and the muscle

thickening of one or both of the superficial and deep fascial layers

Although fascial fluid collections are typically non-focal, abscesses may be seen.

On contrast-enhanced CT, diffuse enhancement of fascia and/or underlying muscle can be seen but is present in both necrotizing or non-necrotizing fasciitis 8,10. On the other hand, absent enhancement of the thickened fascia suggests necrosis 7.

MRI

MRI is the gold standard imaging modality for the investigation of necrotizing fasciitis with high sensitivity (93%) 12 but low specificity 20. MRI has a high negative predictive value 20. Findings include 10,12,20:

-

T2 FS or STIR

fascial thickening ≥3 mm and hyperintensity, starting in the superficial fascia and often involving deep intramuscular fascia in multiple compartments

subfascial and interfascial fluid collections

low signal foci of gas

subcutaneous edema, although commonly seen with cellulitis as well

-

T1

subtle loss of muscle texture and possible high signal intensity compatible with intramuscular hemorrhage

low signal foci of gas

-

T1 C+ (Gd)

variable fascial contrast enhancement: increased early due to capillary permeability but absent later due to necrosis

Treatment and prognosis

Necrotizing fasciitis is an emergency; urgent commencement of empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics including anaerobic is recommended, with subsequent culture results guiding ongoing antibiotic selection.

Urgent surgical fasciotomy with aggressive debridement of the necrotic tissue may be life-saving and may be repeated until there is no further tissue necrosis (this may require amputation). Mortality ranges between 9-25% 17 and the disease can be rapidly fatal within days.

History and etymology

The entity was described by Hippocrates in the 5th century BC as a complication of erysipelas, termed hospital gangrene in a large series by Joseph Jones (an American army surgeon during the American Civil War), and finally called "necrotizing fasciitis" in 1952 in an article by B Wilson 18.

Differential diagnosis

For soft tissue inflammatory findings, consider 12,13:

non-necrotizing fasciitis, cellulitis, and/or myositis

ischemic myonecrosis

For gas within soft tissues, consider:

gas gangrene (clostridial myonecrosis)

penetrating trauma or percutaneous/surgical procedure

communication from the aerodigestive tract (e.g. pneumomediastinum, esophageal perforation)

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.