Pulmonary infarction occurs secondary to vascular obstruction or occlusion 11. It is one of the key complications of pulmonary embolism (PE).

On this page:

Epidemiology

Pulmonary infarction occurs in the minority (10-15%) of patients with PE 1. However, in a necropsy study of those with lethal PE, 60% of cases developed infarction 2.

Historically, it was thought that pulmonary infarction was more common in older patients with comorbidities, especially coexisting cardiovascular disease and underlying malignancy, but rare in the young and otherwise healthy. However, research in 2015 questioned orthodox thinking with evidence that greater patient stature, decreased age (peak risk at age 40), and smoking of cigarettes are independent risk factors for developing pulmonary infarction 2,3. Furthermore, it was shown that heart failure, malignancy and pneumonia were not risk factors for the development of pulmonary infarction 2.

Moreover, the greater the embolic burden, the higher the likelihood of developing lung infarction 1,4-6.

Clinical presentation

Pleuritic chest pain, on its own or with sudden breathlessness, is the most frequent presenting symptom. Hemoptysis is significantly less common (<20% radiologically-diagnosed infarctions in a 2015 study of 335 patients) 3,7.

Pathology

The lungs are not commonly infarcted, as they are supplied by two vascular systems with many anastomoses between them:

-

pulmonary vascular system

carries blood from the right ventricle through the pulmonary arteries to the alveolar capillary system

from there, blood flows through the pulmonary veins into the left atrium and the systemic circulation

-

bronchial vascular system

consists of bronchial arteries that are responsible for the majority of oxygen supply to the lung parenchyma

form a broad network with pre- and postcapillary anastomoses to the pulmonary system

bronchial arteries have the ability to increase their flow by up to 300%

Thus, an occlusive pulmonary vascular lesion does not usually result in infarction because of alternative perfusion via collateral pathway. In addition the lung also receives oxygen from the inspired air itself 3.

Following an occlusive pulmonary embolus, the bronchial arteries are recruited as the primary source of perfusion for the pulmonary capillary network. The higher pressure of the bronchial arteries, in combination with locally increased vascular permeability and capillary endothelial injury, is thought to result in local pulmonary capillary hemorrhage.

Usually these parenchymal findings are transient; the blood cells extravasated into the alveolar and bronchial cavities are resorbed, and the tissue regenerates ref. However, the injury may progress to infarction in certain circumstances:

reduced flow in the bronchial arteries (e.g. shock, hypotension, use of vasodilators)

increased pulmonary venous pressure (e.g. elevated pulmonary venous pressure, interstitial edema)

In these cases, visceral perfusion is catastrophically compromised and the insult progresses to infarction. The necrotic parenchyma will be replaced by fibrous tissue and leads to a collagenous plate-like mass with pleural retraction 4-6.

The lungs are most at risk for infarction when distal vessels ≤3 mm in diameter are occluded, as opposed to central pulmonary artery occlusion 3-5. This is because there is more likely to be sufficient collateral circulation in a central obstruction.

Location

Pulmoary infarction is more common in the right lung, however the reason for this is not known 2,3.

Radiographic features

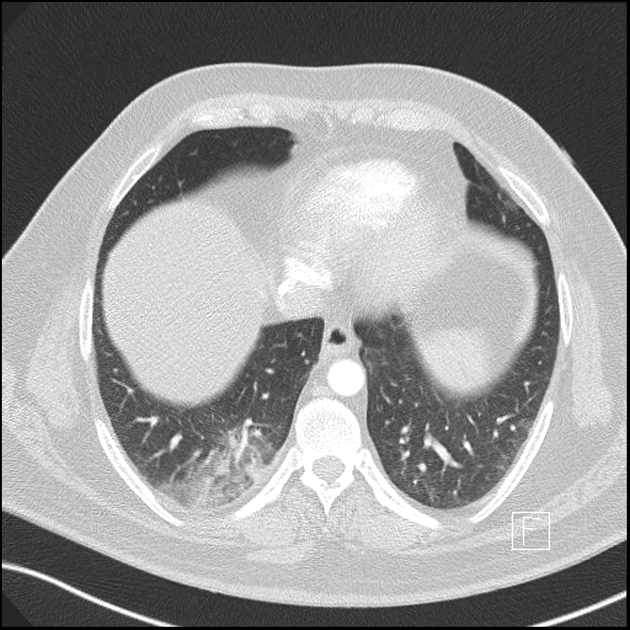

In the acute/subacute setting, it may be difficult to differentiate ischemic pulmonary hemorrhage from actual lung infarction. The evolution of findings over time is helpful, as hemorrhage without infarction usually resolves within a week, while infarction evolves over months and results in parenchymal scarring.

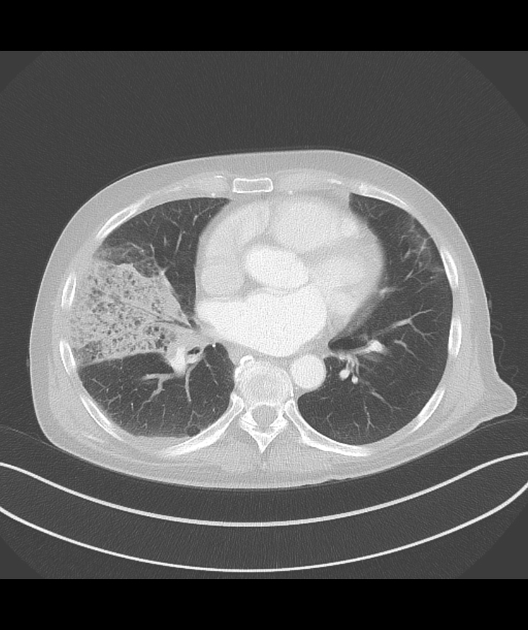

It is important to note that infarction invariably occurs in a subpleural location, whilst malignancy or pneumonia can occur centrally 3.

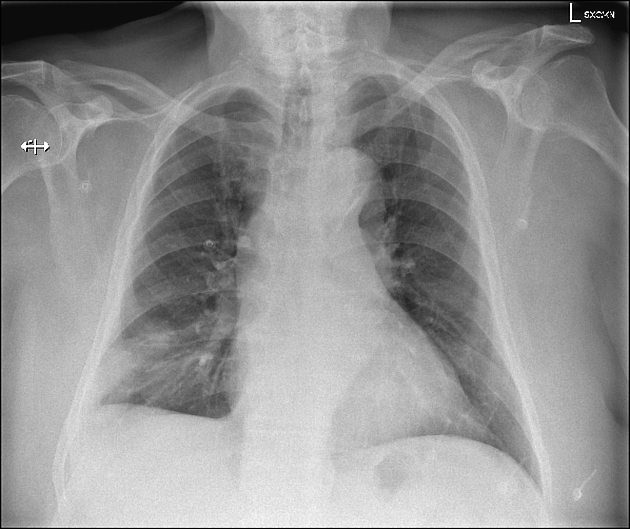

Plain radiograph

Typical chest radiographic findings include 1,8,11:

triangular, dome-, or wedge-shaped (less often rounded) juxtapleural opacification (Hampton hump) without air bronchograms representing edema, hemorrhage, organization and/or scarring

more often in the lower lobes

in the case of pulmonary hemorrhage without infarction, the opacities resolve, usually within a week, by maintaining their shape (the so called "melting sign") - this is transient edema/hemorrhage and not true "infarcts" 11

in the case of infarction, it requires months to heal and may leave a linear scar

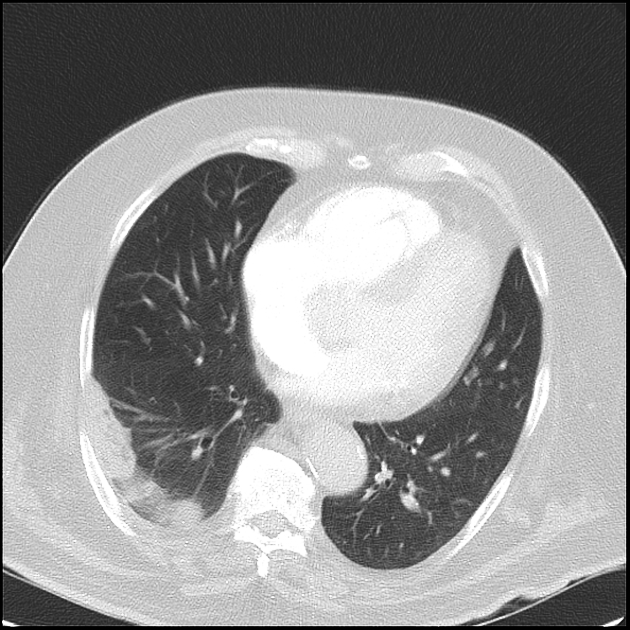

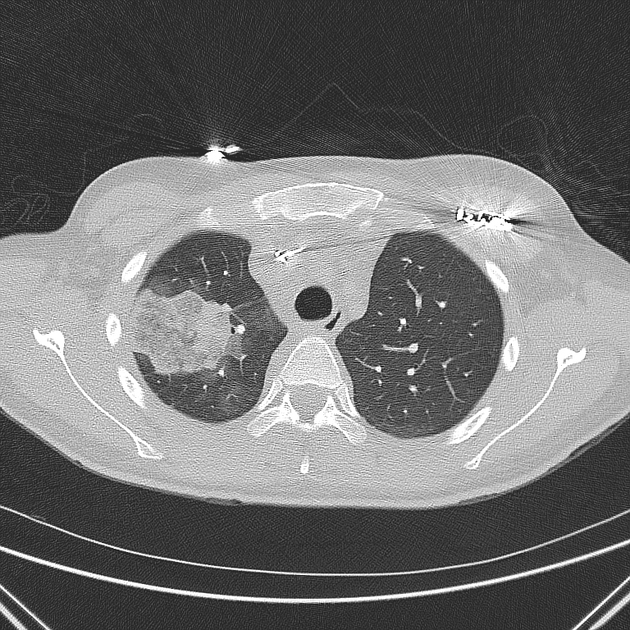

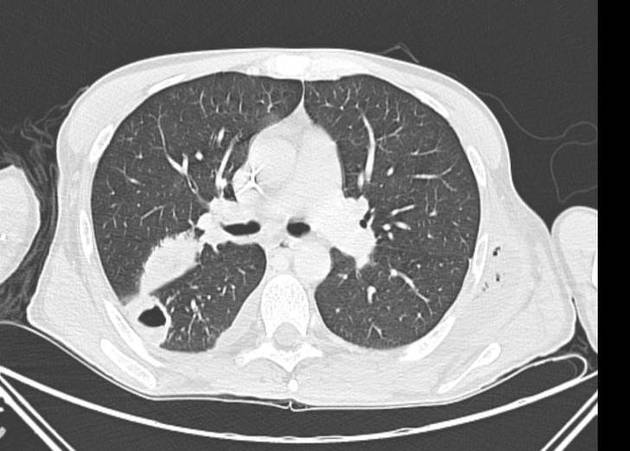

CT

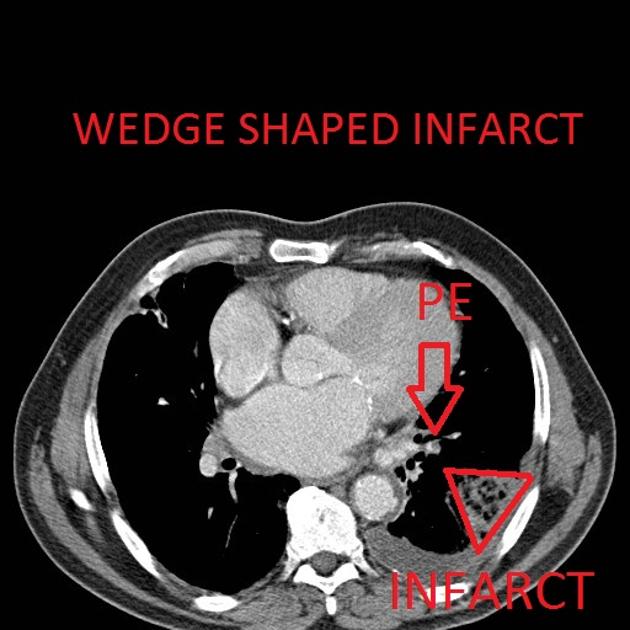

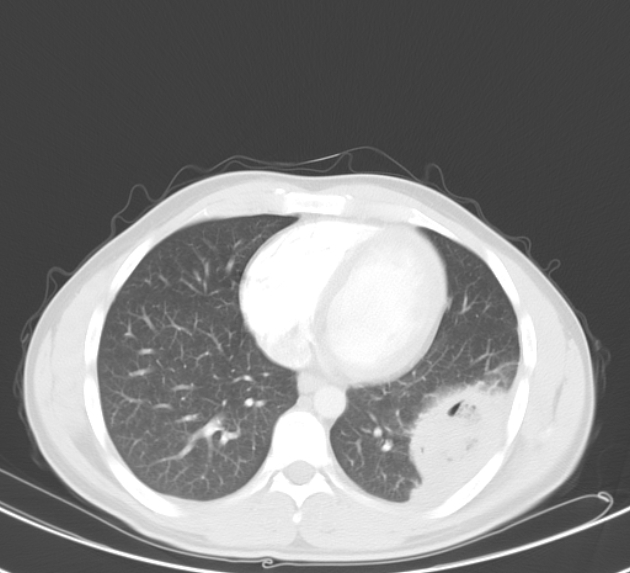

Peripheral wedge-shaped pulmonary consolidations are a classic manifestation of pulmonary infarct, particularly in the setting of a PE.

Recognized features include 1,8,11:

triangular, dome-, or wedge-shaped (less often rounded) juxtapleural opacification (Hampton hump) without air bronchograms representing edema, hemorrhage, organization and/or scarring

-

consolidation with internal air lucencies, "bubbly consolidation"

represents non-infarcted aerated lung parenchyma co-existing side-by-side with infarcted lung in the same lobule 9

convex borders with a halo sign secondary to adjacent hemorrhage

-

decrease in normal lung enhancement

may be scattered areas of low attenuation within the lesion (necrosis)

sometimes appears as hyperenhancement of the infarct perimeter

cavitation: may be seen in septic embolism and infection of a bland infarct (cavitatory pulmonary infarction)

Nuclear medicine

PET-CT

A rim sign has been described on FDG-PET of pulmonary infarction, with mild peripheral tracer uptake, and an absence of uptake centrally 10.

Treatment and prognosis

Treating the underlying pulmonary embolism by providing cardiopulmonary support is the initial treatment. Anticoagulation is commenced in patients without risk of active bleeding. If the emboli are massive, thrombolysis is also an option. In some cases, embolectomy, and placement of vena cava filters are required.

Differential diagnosis

For peripheral wedge-shaped lesions on CT, consider:

pulmonary hemorrhage (ischemia change without infarction)

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.