Malignant pleural disease usually heralds a poor prognosis, whether it represents a primary pleural malignancy or metastatic disease.

On this page:

Epidemiology

The incidence of malignant pleural effusion is approximately 150,000 per annum in the USA and 50,000 per annum in the UK and affects ~20% of cancer patients 11. Lung and breast cancer account for >50% of malignant pleural effusions, and malignancy accounts for about one-third of exudative effusions 12.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by guided pleural biopsy, pleural fluid analysis and imaging. Light’s criteria can mistake 5-10% of malignant pleural effusions for transudates 11. Low pH and glucose predict the extent of pleural involvement, number of tumour cells and pleurodesis success 11. Guidelines vary, but pathology guidelines advise sending as much fluid as can be aspirated safely. Cytological diagnosis is more likely with primary lung adenocarcinoma than haematological malignancies and mesothelioma 11. Thoracoscopy and VATS are more invasive, and VATS requires general anaesthesia and single-lung ventilation.

Clinical presentation

Patients may be asymptomatic or present with breathlessness, pain or cough 12. Early pleural disease may be evident as pleural nodules or thickening and may progress to pleural effusion and non-expandable lung. Localised pain may indicate chest wall invasion and may be accompanied by a palpable mass.

Pathology

The pleura can be involved by malignancy by the following mechanisms:

direct extension from an adjacent tumour, e.g. lung cancer

primary tumour, e.g. mesothelioma, primary pleural lymphoma

pleural metastases, usually haematogenous spread to the visceral pleura with subsequent spread to the parietal pleura through adhesions or implantation of tumour cells.

pleural seeding, which is relatively common in invasive thymic tumour and lung adenocarcinoma

In each of these, the manifestation can be either solid disease or a malignant pleural effusion, or a combination of both. Pleural fluid seems to provide a nutrient rich and immune-supressed environment which promotes tumour growth 11.

The relative aetiology of malignant pleural disease is 1,6:

metastatic carcinoma (e.g. primary lung): 58%

mesothelioma: 28%

breast

metastatic melanoma

invasive thymoma

-

rare primary pleural malignancies 7

Radiographic features

Conventional imaging is in general highly specific for the diagnosis of pleural malignancy but unfortunately lacks sensitivity 3.

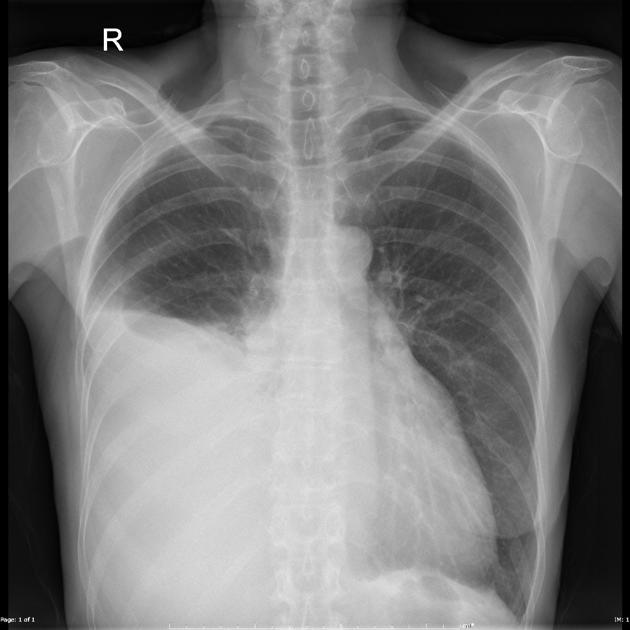

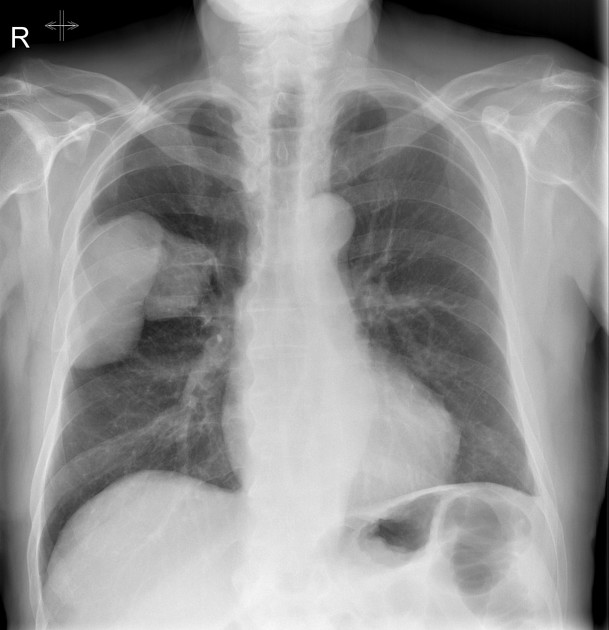

Plain radiograph

Frontal chest x-ray can detect fluid as little as 175 mL, but has low sensitivity below volumes of 500 mL ref. X-ray features of malignancy are not often seen; they include pleural nodularity and involvement of the mediastinal pleura. Lung or bone metastases, chest wall invasion and lymphadenopathy are helpful signs of malignancy.

Ultrasound

Transthoracic ultrasound readily detects small effusions and can detect pleural tumour deposits that cause pleural thickening and nodularity 11. Ultrasound guidance is used to assist biopsy and to identify intercostal vessels before procedures such as biopsy and drainage.

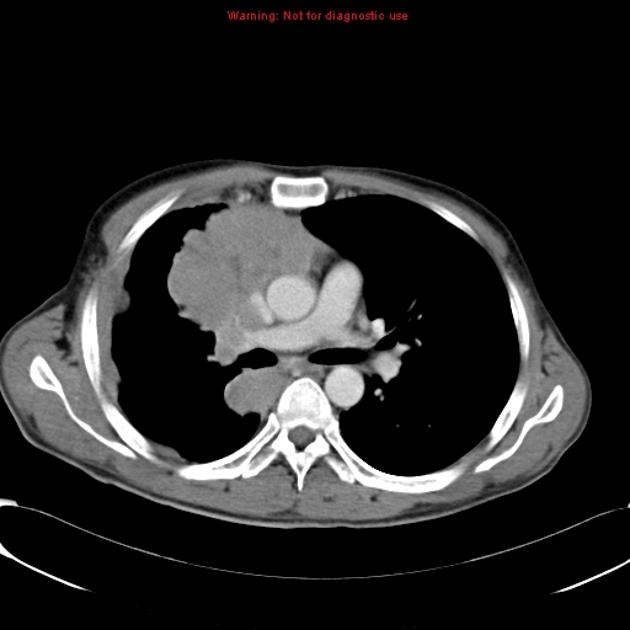

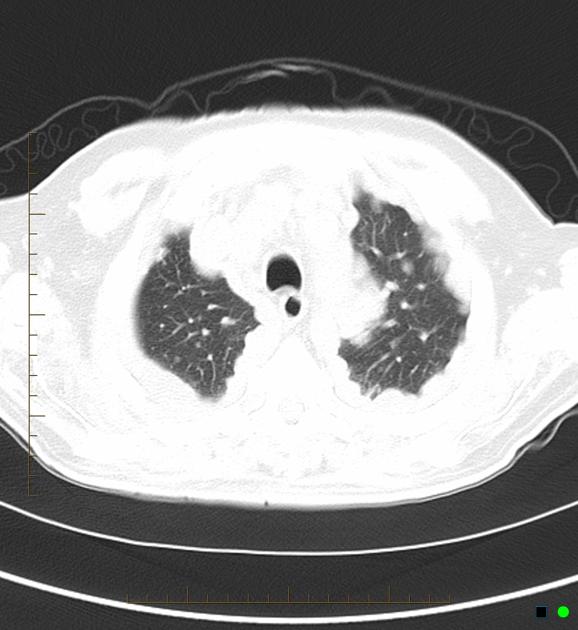

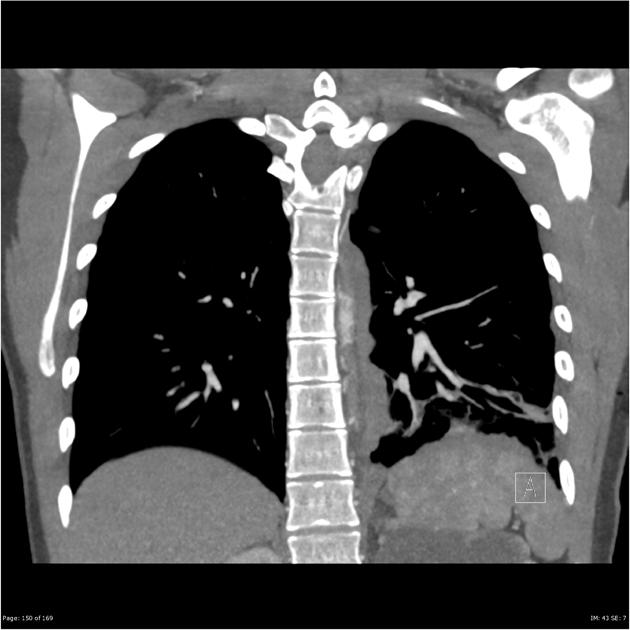

CT

CT is the work-horse of pleural imaging, able to achieve specificities of close to 100% 3. The pleura enhances maximally during the portal-venous phase (also known as the pleural phase in the chest). A number of features are recognised in differentiating benign from malignant, including 1,3,8:

parietal pleural thickening >1 cm

mediastinal pleural thickening or nodularity

interruption of pleural thickening 8

Diffuse pleural calcification overlying pleural thickening suggests a benign process and extrapleural fat hypertrophy is a feature of chronic inflammation.

In many cases the primary malignancy will be visible (e.g. breast cancer, lung cancer) and there may be evidence of pulmonary, upper abdominal, or bone metastases.

Nuclear medicine

FDG-PET is highly sensitive for malignant pleural disease 3 but can be falsely positive in inflammatory disease or post pleurodesis 11. Hypermetabolism can be seen in either the pleura or pleural effusion. SUV of ≥2.0 favours benign disease 3. FDG-PET can help identify an optimal site for pleural biopsy and demonstrates nodal and metastatic disease elsewhere.

MRI

MRI findings of high signal intensity on T2 in relation to intercostal muscles and/or contrast-enhanced on T1 images together with CT morphology has a 100% and a specificity of 93% in the detection of pleural malignancy 5.

Treatment and prognosis

Malignant pleural disease is generally incurable and the aim should be palliation and quality of life. The median survival of malignant pleural effusion is 3-12 months 12. In the case of primary malignancies of the pleura (e.g. mesothelioma) resection may be a possibility in highly selected cases.

Thoracentesis can be diagnostic and ease breathlessness. 1-1.5 L can be withdrawn at any one time and this can also help assess the presence or absence of non-expandable lung. Reperfusion pulmonary oedema can be fatal and is more likely with rapid withdrawal of large volumes of fluid, longer duration of effusion (>1 week) and younger age 12.

Talc pleurodesis is appropriate if good apposition of visceral and parietal pleura can be maintained but is unlikely to be successful in the case of non-expandable lung.

Tunnelled indwelling pleural catheter may shorten hospital stay and sometimes achieves pleurodesis. It is less risky compared to VATS.

Chemotherapy, immunotherapy including immune checkpoint inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies, antiangiogenic therapy, targeted therapy and radiotherapy have a place in treatment. Intrapleural bevacizumab and chemotherapeutic agents are the subject of ongoing study and may offer a therapeutic advantage 12.

Specific options are discussed separately as part of articles pertaining to individual malignancies:

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis depends on the predominant form the pleural disease takes:

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.