Pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) infection is a type of non-tuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) infection. It is relatively common and continues to pose significant therapeutic challenges. In addition, the role of MAC in pulmonary pathology remains controversial in many instances.

On this page:

Epidemiology

MAC infections often occur in patients with a pre-existing pulmonary disease or those with depressed immunity. However, it is also seen frequently in otherwise healthy patients, with a predilection for older women who deliberately suppress the cough reflex (Lady Windermere syndrome) 1-3.

Associations

A number of patient groups have been associated with increased risk of pulmonary MAC. They include 2,3:

elderly, white, thin women: nodular bronchiectatic form (Lady Windermere syndrome)

middle-aged or elderly males who are smokers (often with COPD) or alcoholics: upper lobe cavitary form (see below)

immunocompromised patients, e.g. AIDS

patients with cystic fibrosis: MAC isolated in up to 13% of patients

patients with alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency

other causes of bronchiectasis

Isolation of MAC from a patient's lung is not pathognomonic of infection, as colonization is common, and thus microbiology needs to be correlated with clinical and radiographic appearances 2,3.

Clinical presentation

Pulmonary MAC infection is typically insidious, with a chronic cough usually productive of purulent sputum being most common. Hemoptysis and constitutional symptoms are not typical 2.

Pathology

Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare are now considered together, and referred to as Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) or Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAIC). They cannot be distinguished on the grounds of human pathologic manifestation or imaging features, and are treated similarly, although M. avium has a predilection for chickens whereas M. intracellulare prefers rabbits 2,3.

Mycobacterium chimaera is also considered a relatively low-virulent member of this group (see pulmonary mycobacterium chimaera infection).

They are ubiquitous organisms, found in both fresh and salt water, but do not tend to cause human disease. Patients with MAC infection, unlike those with pulmonary tuberculosis, are not contagious 2.

Variants

hot tub lung: granulomatous pneumonitis from exposure to aerosolized MAC organisms in contaminated water (may not necessarily imply infection) 4

Radiographic features

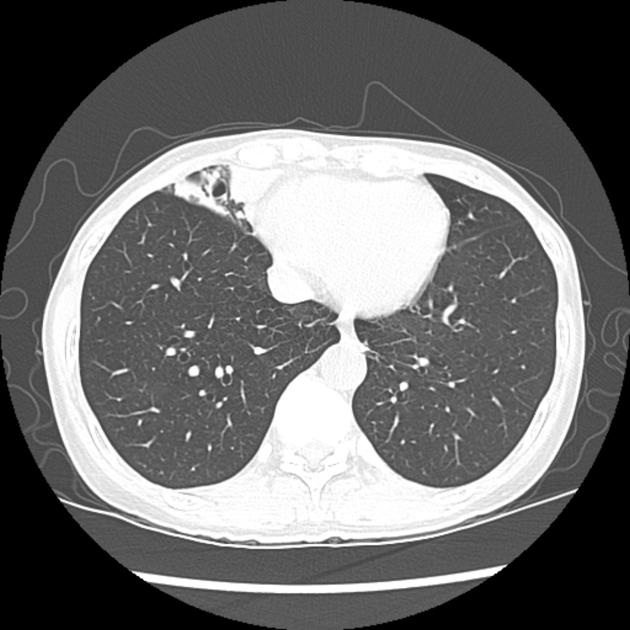

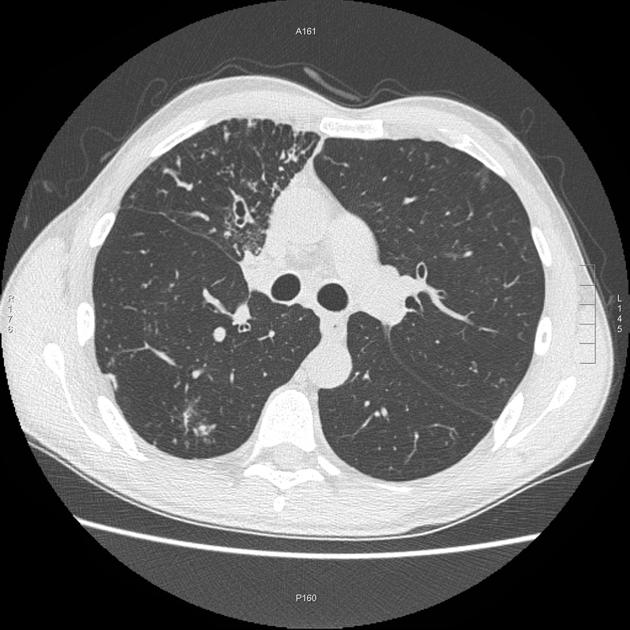

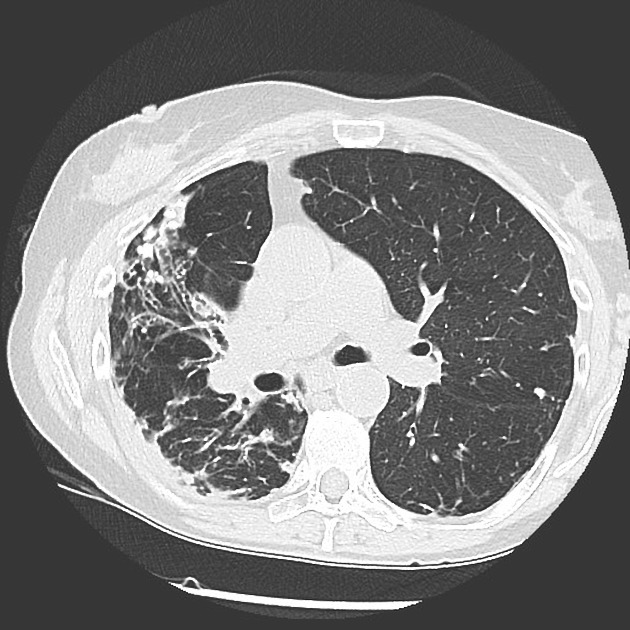

Three main forms of pulmonary MAC infections are recognized 3,5,6:

upper lobe fibrocavitary pattern / cavitary form (classic infection)

nodular bronchiectatic form / bronchiectatic form (non-classic infection)

mixed form

In upper lobe cavitary form, thin-walled cavities with overall volume loss and fibrosis are the dominant feature, often also with features of endobronchial spread with tree-in-bud opacities seen elsewhere.

In the nodular or non-classic manifestation, the dominant feature is bronchiectasis with associated centrilobular nodules. Unlike pulmonary tuberculosis, there is no predilection for the upper lobes. In elderly white females, the right middle lobe and lingula are particularly affected.

Plain radiograph

Bronchiectasis, seen as tram-track opacities and ring shadows, may be evident. Patchy airspace opacities are also common. Pleural effusions are uncommon 2. Upper zone cavities may also be seen with associated volume loss and scarring 3.

CT

The most common findings of MAC infections include 1,2:

bronchiectasis and bronchial wall thickening: most common findings

small centrilobular nodules and tree-in-bud appearance

patchy consolidation

a predilection for the right middle lobe and lingula is seen particularly in elderly white women

pleural thickening may be seen, usually adjacent to parenchymal change

upper lobe cavitation may also be seen, although it is more characteristic of pulmonary tuberculosis

Occasionally it may manifest as mass-like consolidative areas or nodular mass-like regions 7.

Treatment and prognosis

Many treatment regimens have been published, with no clear gold standard evident, although as is the case with pulmonary TB, multi-drug therapy is ideal to avoid resistance 2.

In patients who are unable to tolerate medical management, and who have an adequate respiratory reserve, resection of affected portions of the lung may be undertaken. Complications of surgery include bronchopleural fistulas, hemoptysis, and empyema 2.

In patients in whom isolates of MAC are not clearly pathogenic, follow-up is required, keeping in mind that evidence of radiographic progression may take a number of years to be convincing 3.

Prognosis depends on the form of the disease. In the upper lobe cavitary form, lung destruction is usually progressive and can lead to respiratory failure and death if successful treatment is not instituted.

In patients with the nodular bronchiectatic form (Lady Windermere syndrome) the disease is much more indolent, however, eventually, this form may also lead to enough parenchymal damage to result in respiratory failure and death 3.

Large cavity size and consolidation on CT showed have to shown to have strong relationships with disease progression on cavitatory forms on some studies 9.

Differential diagnosis

-

Mycobacterium tuberculosis pulmonary infection:

bronchiectasis is less commonly the dominant feature 1

changes usually in the upper lobes 1

in rare situations some nodular forms can occasionally mimic lung cancer 7

see other causes of bronchiectasis

The underlying pulmonary abnormality (e.g. COPD, pneumoconiosis) may dominate the radiographic appearance.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.