Pneumothorax (PTX) (plural: pneumothoraces) refers to the presence of gas in the pleural space which allows the parietal and visceral pleura to separate and the lung to collapse. The clinical consequences range from negligible to haemodynamic collapse and death.

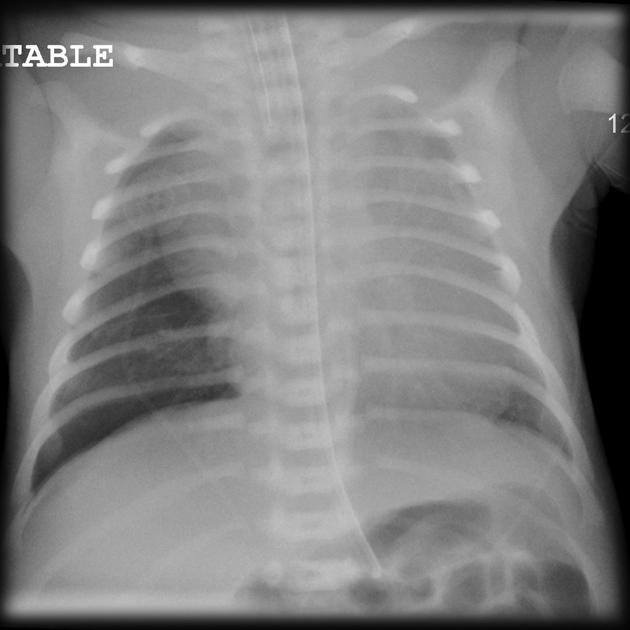

Neonatal pneumothorax has its own dedicated article.

On this page:

Terminology

A simple pneumothorax is a non-communicating pneumothorax without tension.

A communicating (a.k.a. open) pneumothorax describes pneumothorax associated with a chest wall defect which may be under tension.

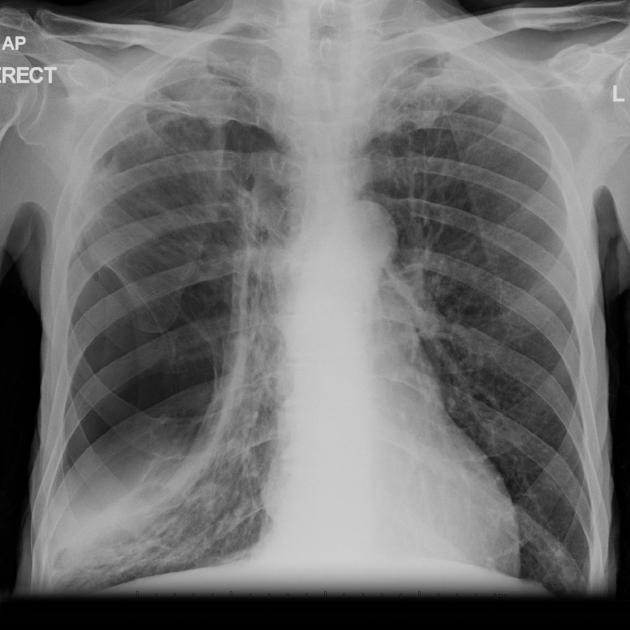

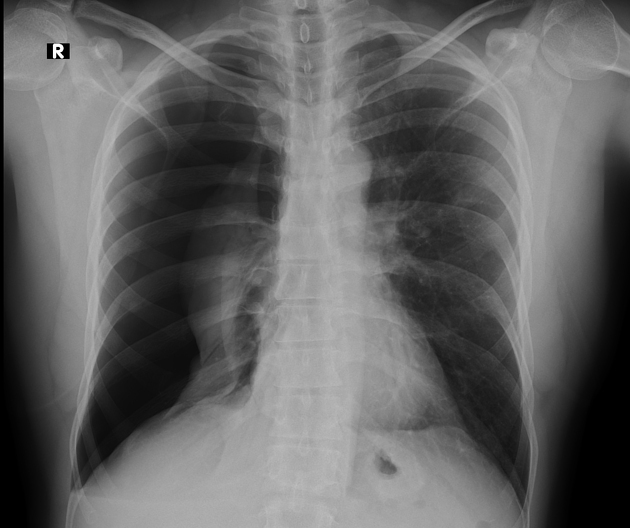

In tension pneumothorax a check-valve mechanism results in progressive enlargement of the pneumothorax which exerts pressure on the diaphragm and mediastinum, narrowing the superior vena cava and other blood vessels. Obstructed venous return may cause cardiovascular collapse and death.

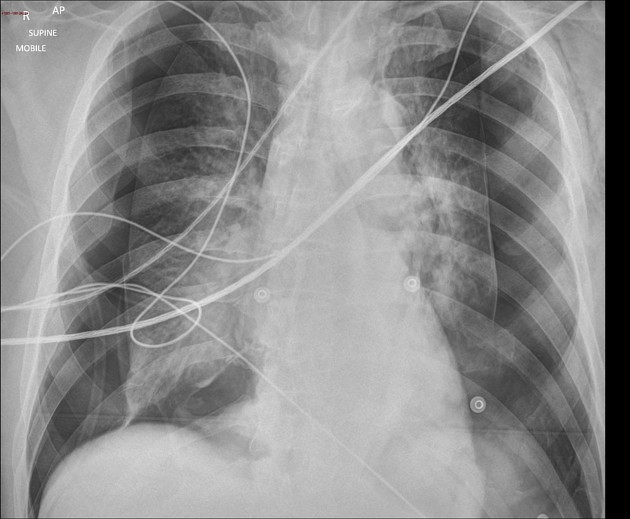

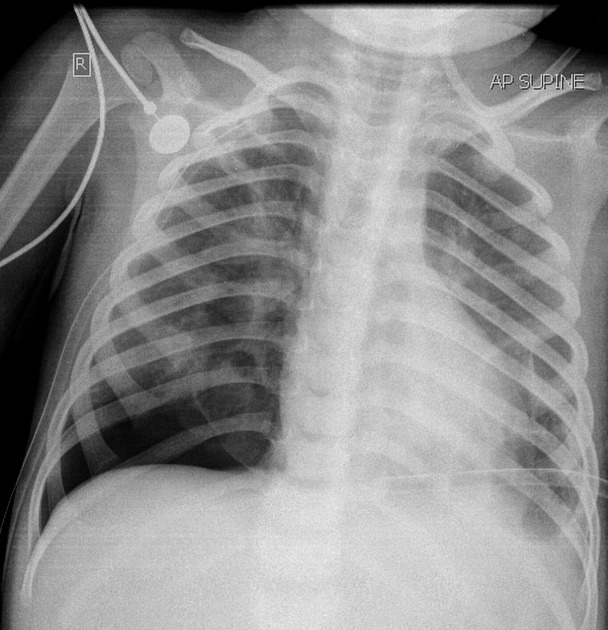

An occult pneumothorax refers to one missed on initial imaging, usually a supine/semierect AP chest radiograph 24.

Epidemiology

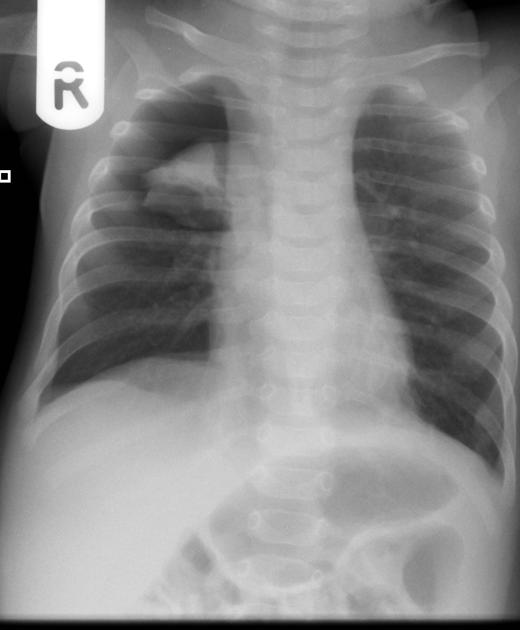

Primary spontaneous pneumothoraces occur in younger patients (typically less than 35 years of age), especially young tall males and smokers who have a much greater lifetime risk, 12% versus 0.1% in non-smokers 25. Recurrence rate in the subsequent three years is between 20-60%. Secondary spontaneous pneumothoraces due to underlying lung disease occur in older patients (typically over 45 years of age) 4. Pneumothorax is a common presentation of cystic lung disease.

Clinical presentation

Presentation is variable and may range from no symptoms to severe dyspnoea with tachycardia and hypotension. In patients with a tension pneumothorax, presentation may include distended neck veins and tracheal deviation, cardiac arrest, and death in the most severe cases.

It is interesting to note that some generalisations can be made regarding the clinical presentation in primary versus secondary spontaneous pneumothoraces:

primary spontaneous: pleuritic chest pain usually present, dyspnoea mild or moderate

secondary spontaneous: pleuritic chest pain often absent, dyspnoea usually severe

Pathology

It is useful to divide pneumothoraces into three categories 4:

primary spontaneous: no underlying lung disease

secondary spontaneous: underlying lung disease is present

iatrogenic/traumatic

Primary spontaneous

A primary spontaneous pneumothorax occurs in a patient with no known underlying lung disease. Tall and thin habitus are more likely to develop a primary spontaneous pneumothorax. There may be a familial component, and there are well-known associations 10:

Secondary spontaneous

When the underlying lung is abnormal, a pneumothorax is referred to as secondary spontaneous. There are many pulmonary diseases which predispose to pneumothorax including:

-

cystic lung disease

honeycombing: end-stage interstitial lung disease

due to apical lung changes from ankylosing spondylitis 1

-

parenchymal necrosis

lung abscess, necrotic pneumonia, septic emboli, fungal disease, tuberculosis

cavitating neoplasm, metastatic osteogenic sarcoma

-

other

catamenial pneumothorax 2,4: recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax during menstruation, associated with endometriosis of pleura

rarely pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis 9

Iatrogenic/traumatic

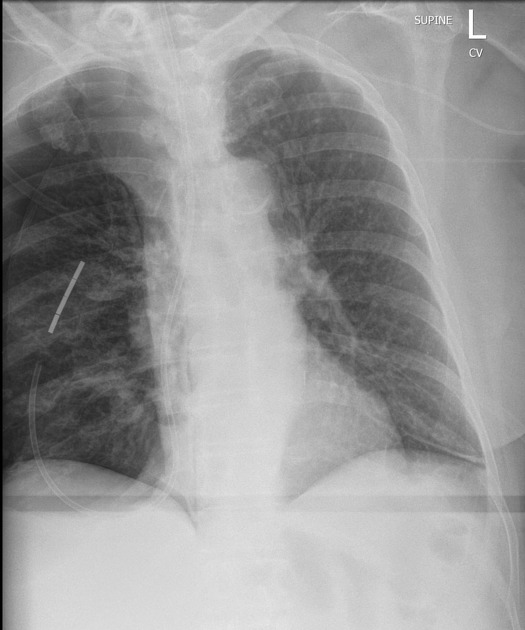

Iatrogenic/traumatic causes include 1-4:

-

iatrogenic:

percutaneous biopsy

barotrauma (e.g. divers), ventilator

radiofrequency (RF) ablation of lung mass

endoscopic perforation of the oesophagus

central venous catheter insertion, nasogastric tube placement

-

trauma:

acupuncture 14,15

Others

pneumoperitoneum with passage through congenital/acquired diaphragmatic defects

buffalo pneumothorax is the presence of bilateral pneumothoraces due to abnormal communication between the left and right pleural spaces

Unusual forms

interlobar pneumothorax / interfissural pneumothorax 17 - form of loculated pneumothorax confined to the fissures

Radiographic features

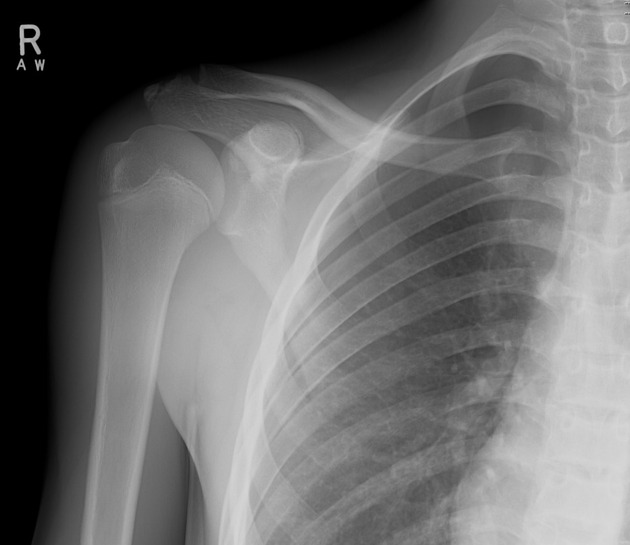

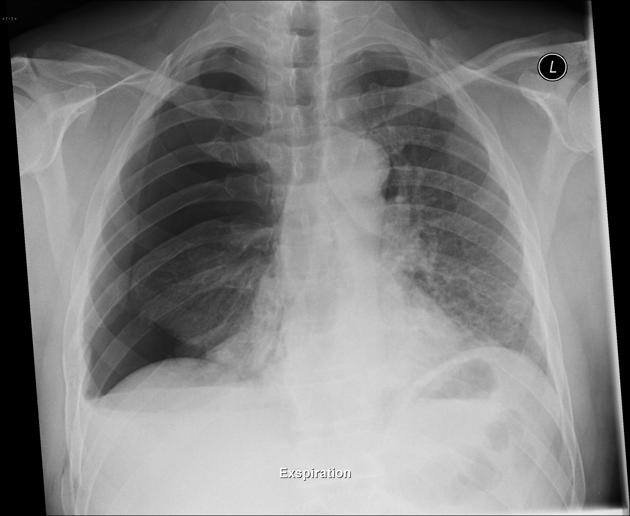

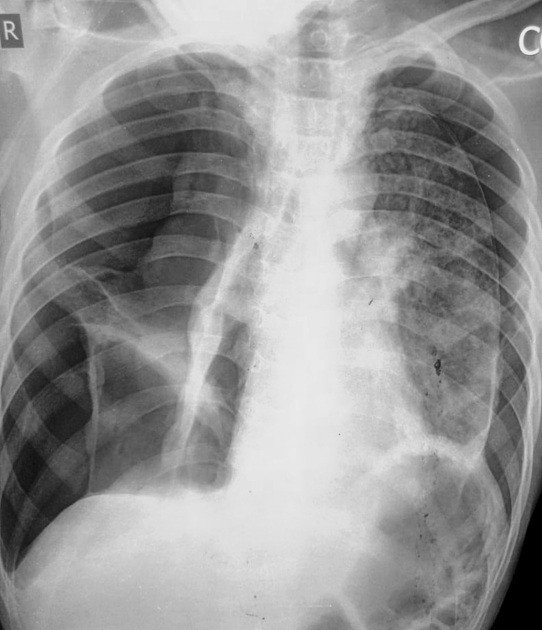

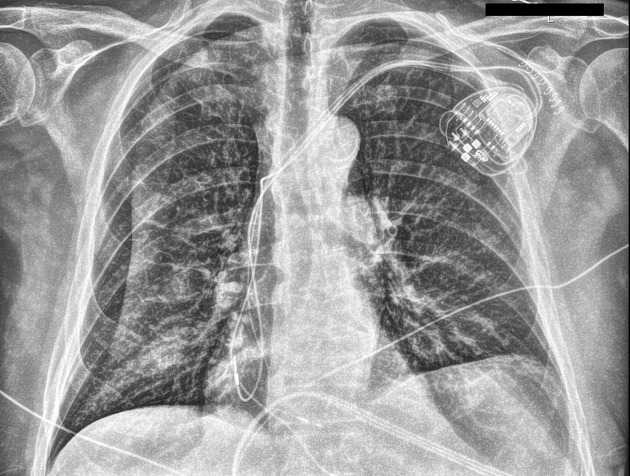

Plain radiograph

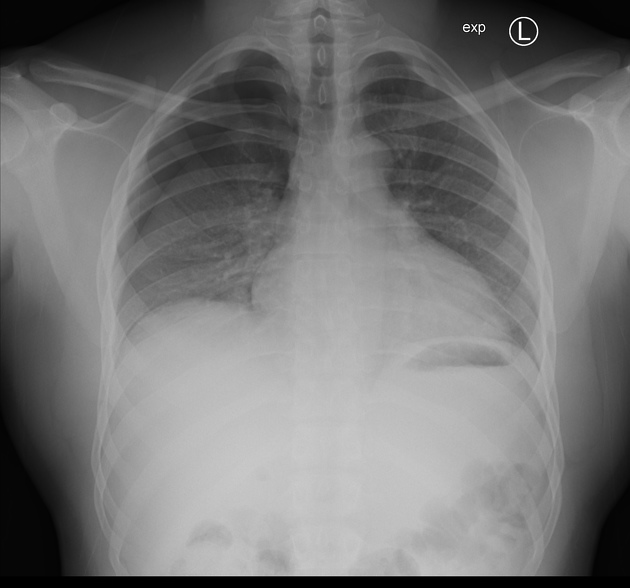

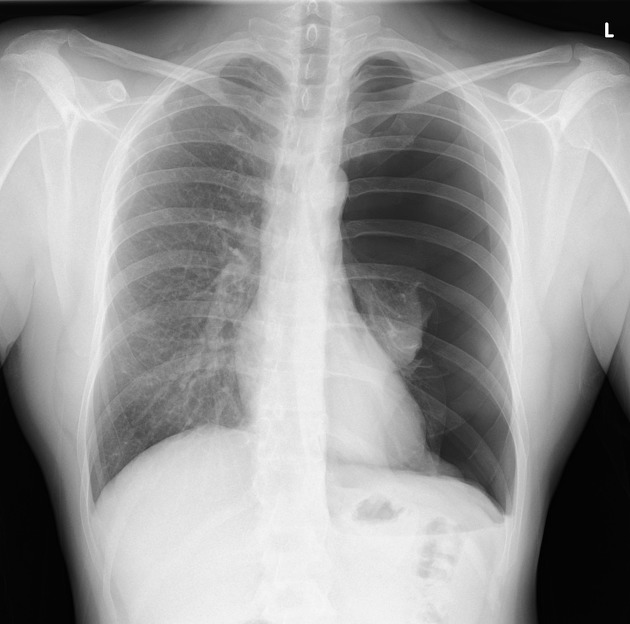

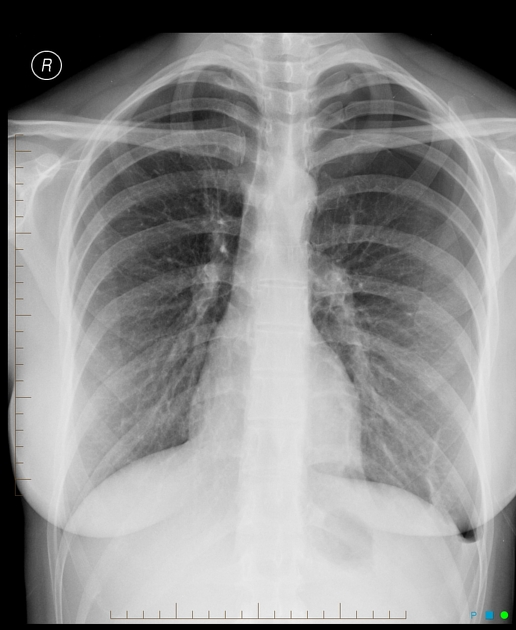

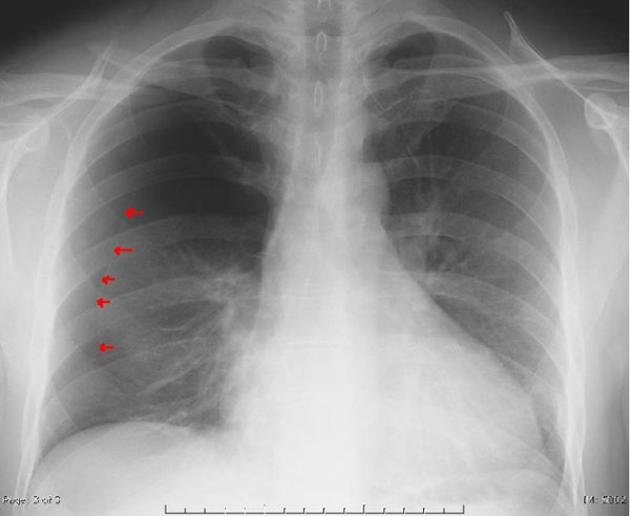

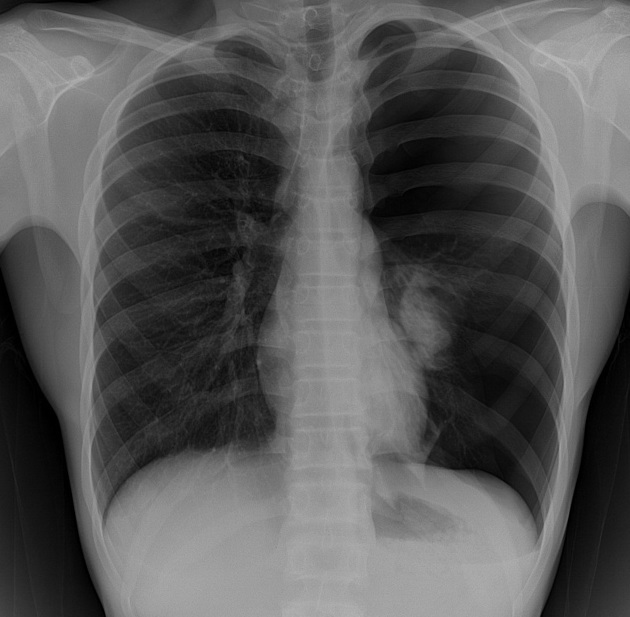

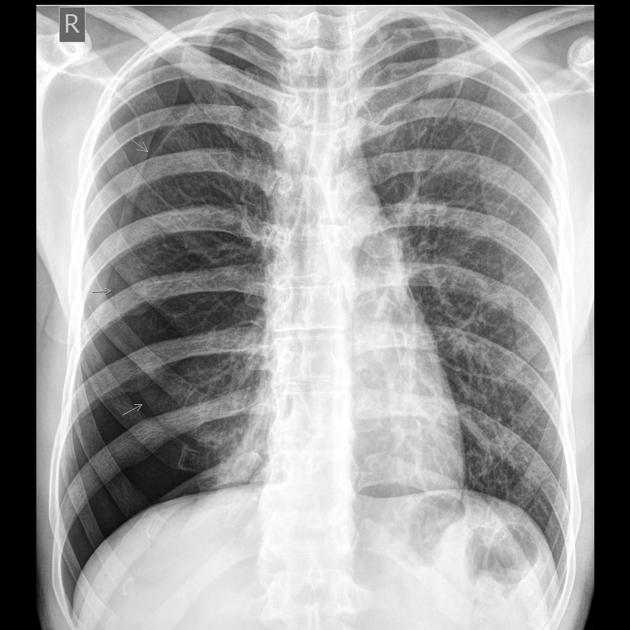

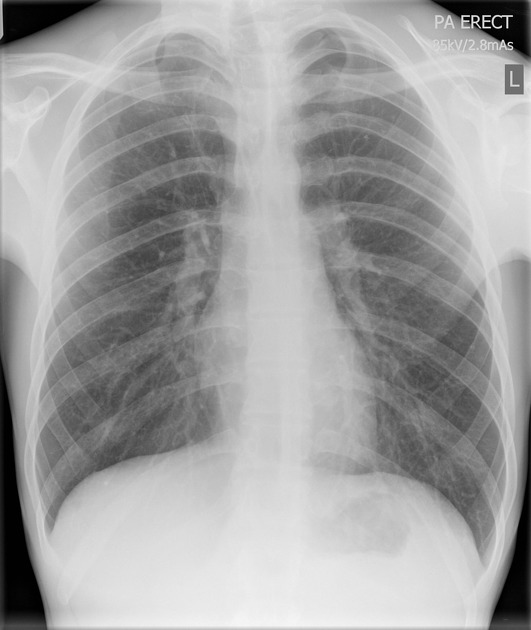

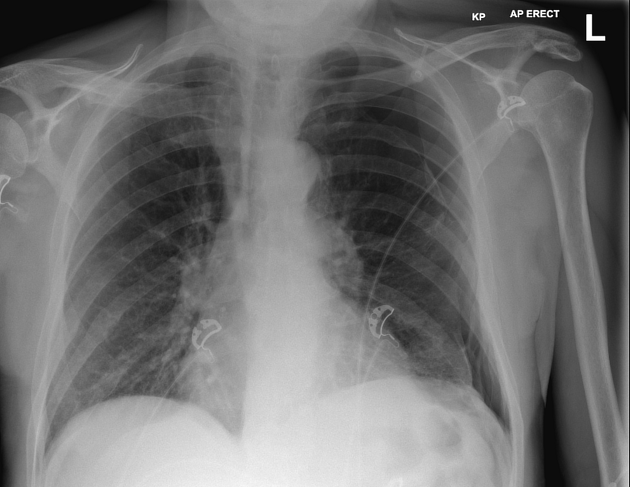

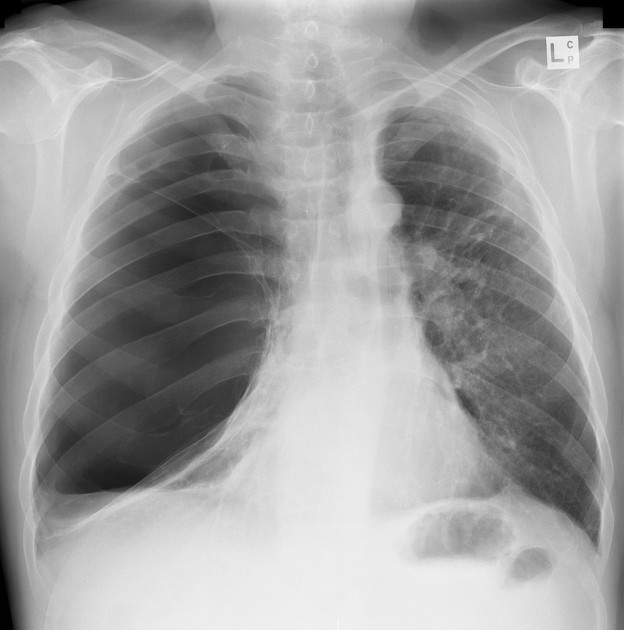

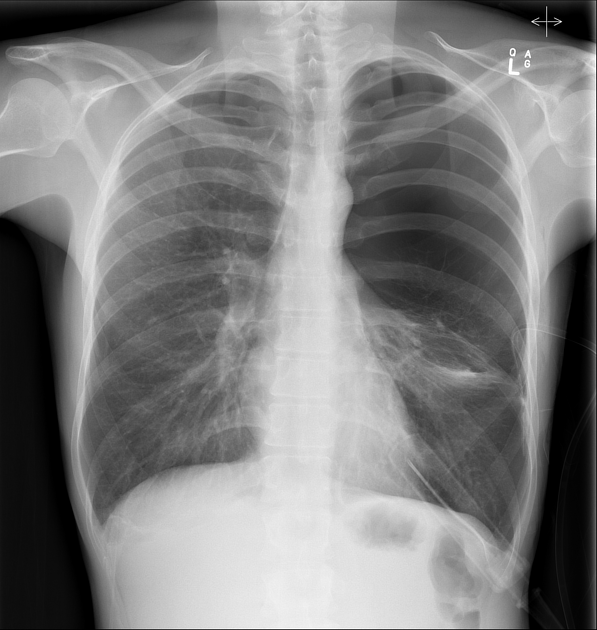

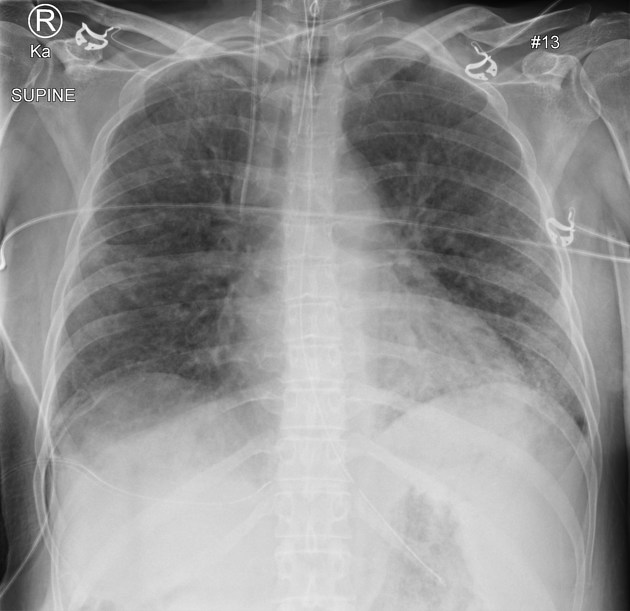

A pneumothorax is, when looked for, usually easily appreciated on erect chest radiographs. Typically they demonstrate:

visible visceral pleural edge is seen as a very thin, sharp white line

no lung markings are seen peripheral to this line

peripheral space is radiolucent compared to the adjacent lung

lung may completely collapse

mediastinum should not shift away from the pneumothorax unless a tension pneumothorax is present (discussed separately)

subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum may also be present

Described methods for estimating the percentage volume of pneumothorax from an erect PA radiograph include:

-

Collins method 19

-

% = 4.2 + 4.7 (A + B + C)

the distances are measured in centimetres

A is the maximum apical interpleural distance

B is the interpleural distance at midpoint of upper half of lung

C is the interpleural distance at midpoint of lower half of lung

-

Rhea method 20

-

Light index 21

% of pneumothorax = 100−(DL3/DH3×100)

DL is the diameter of the collapsed lung

DH is the diameter of the hemithorax on the collapsed side

In cases where a pneumothorax is not clearly present on standard frontal chest radiography a number of techniques can be employed:

-

should be done with the suspected side up

the lung will then 'fall' away from the chest wall

-

lung becomes smaller and denser

pneumothorax remains the same size and is thus more conspicuous: although some authors suggest that there is no difference in detection rate 6

CT chest +/- IV contrast

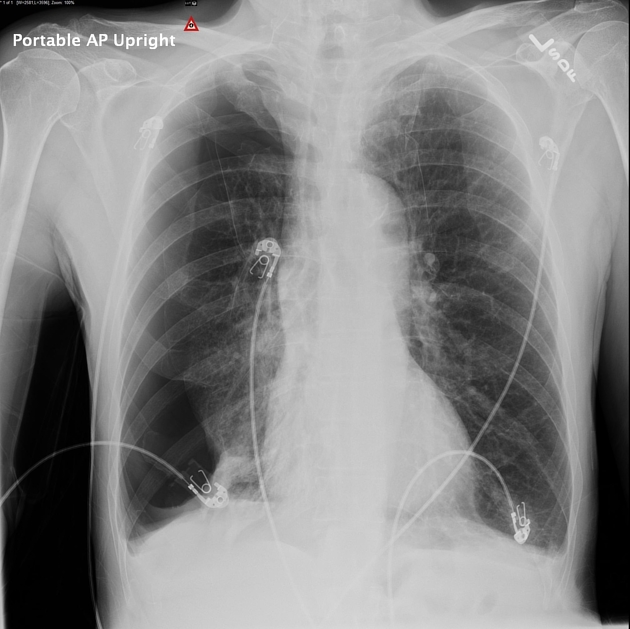

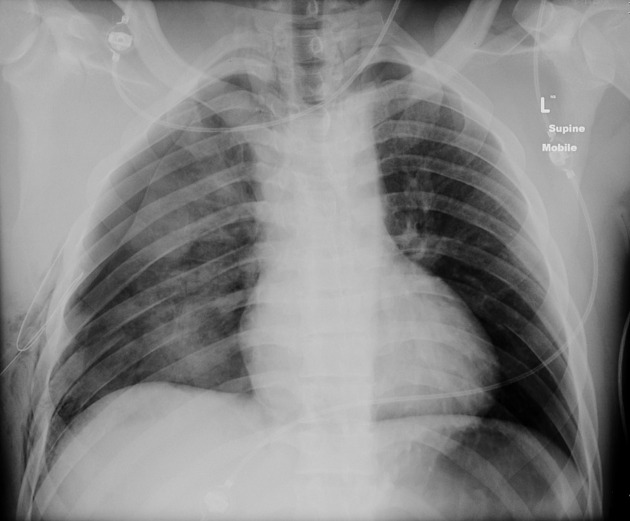

When imaged supine detection can be difficult: see pneumothorax in a supine patient, and pneumothorax is one cause of a transradiant hemithorax.

Ultrasound

M-mode can be used to determine movement of the lung within the rib-interspace. Small pneumothoraces are best appreciated anteriorly in the supine position (gas rises) whereas large pneumothoraces are appreciated laterally in the mid-axillary line.

See: ultrasound for pneumothorax.

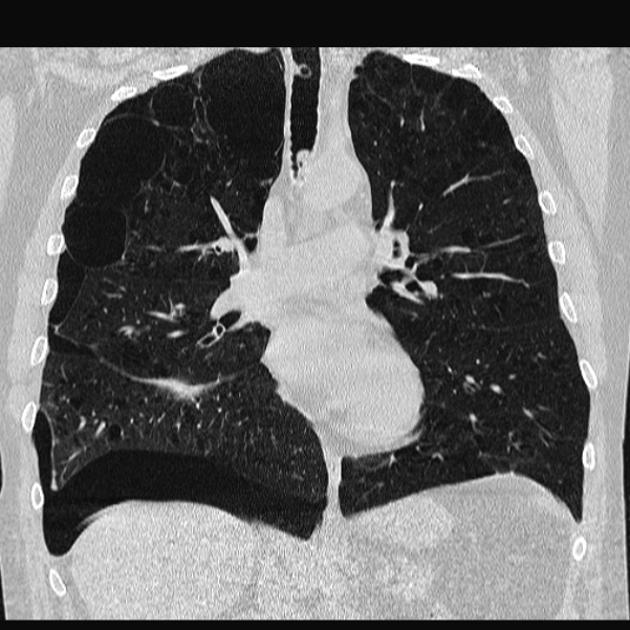

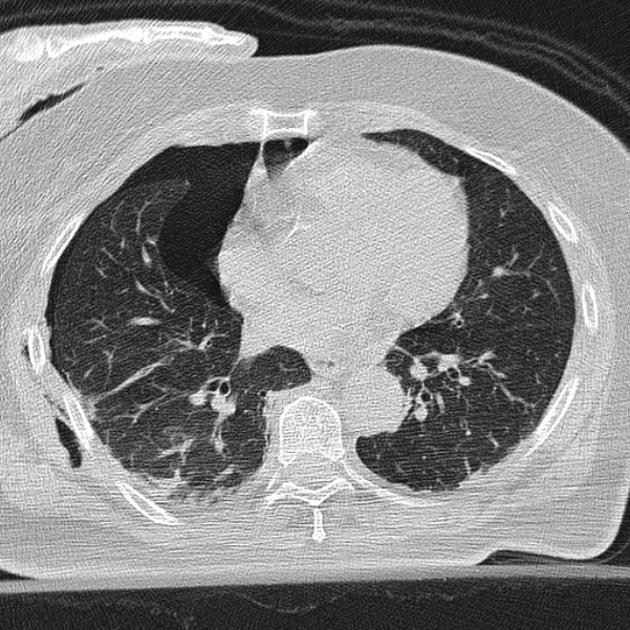

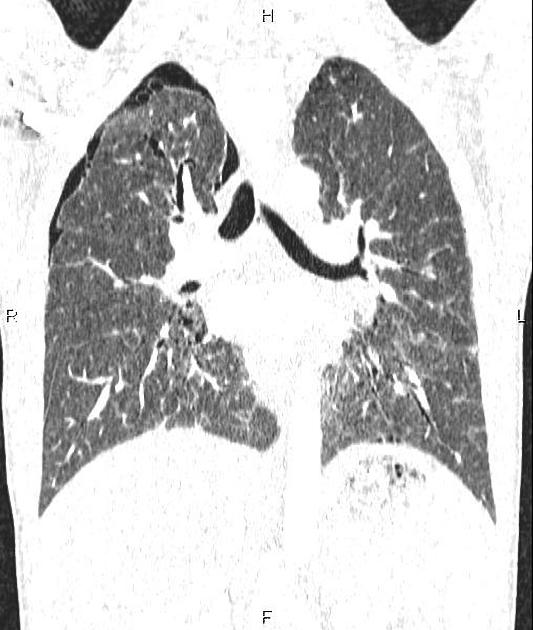

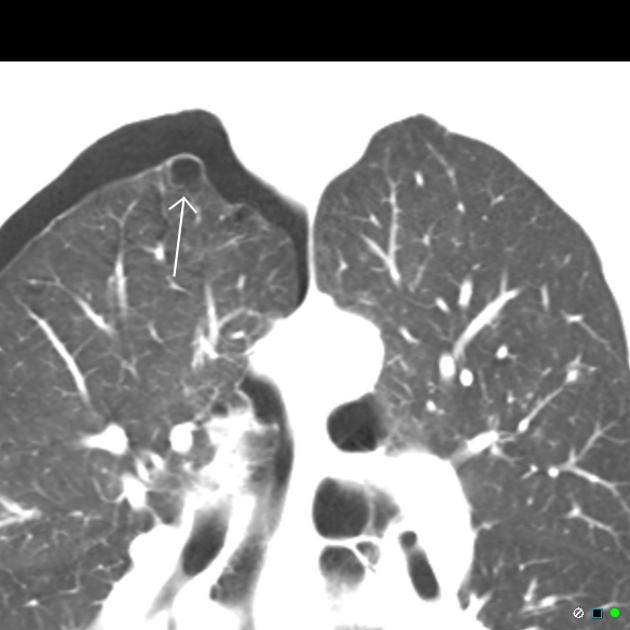

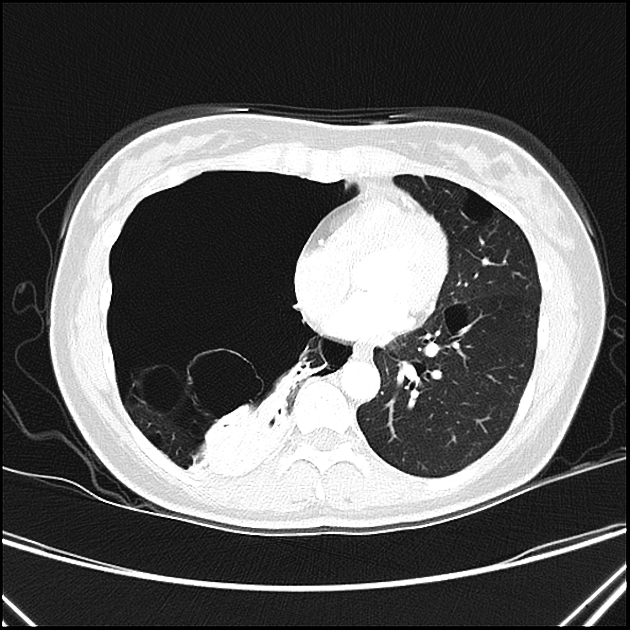

CT

Provided lung windows are examined, a pneumothorax is very easily identified on CT, and should pose essentially no diagnostic difficulty. When bullous disease is present, a loculated pneumothorax may appear similar.

Treatment and prognosis

Treatment depends on a number of factors:

size of the pneumothorax

symptoms

background lung disease/respiratory reserve

Estimating the size of pneumothorax is somewhat controversial with no international consensus. CT is considered more accurate than plain radiograph.

-

British Thoracic Society (BTS) guidelines (2010): measured from chest wall to lung edge at the level of the hilum 12

<2 cm: small

≥2 cm: large

-

American College of Chest Physicians guidelines (2001): measured from thoracic cupola to lung apex 13

<3 cm: small

≥3 cm: large

These can be used together to determine the best course of action. The following is based on the BTS guidelines 12 for the treatment of pneumothorax; local protocols may differ:

asymptomatic small rim pneumothorax: no treatment with follow-up radiology to confirm resolution

pneumothorax with mild symptoms (no underlying lung condition): needle aspiration in the first instance

pneumothorax in a patient with background chronic lung disease or significant symptoms: intercostal drain insertion (small drain using the Seldinger technique)

In trauma patients, the "35 mm rule" predicts which patients can be safely observed. If the pneumothorax measures <35 mm (measuring the largest air pocket between the parietal and visceral pleura perpendicular to the chest well on axial imaging) in stable, non-intubated patients there was a 10% failure rate (i.e. requiring intercostal catheter insertion) during the first week 16.

In patients with recurrent pneumothoraces or at very high risk of recurrent events and a poor respiratory reserve, pleurodesis can be performed. This can either be medical (e.g. talc poudrage) or surgical (e.g. VATS pleurectomy, pleural abrasion, sclerosing agent) 4.

History and etymology

Pneumothorax is derived from two Greek words, πνευμα (pneumα) meaning breath and θωραξ (thorax) meaning breastplate. The synonym, aerothorax, which is rarely, if ever, seen in modern medicine also has Greek roots, from αερος (aero) meaning air 22,23.

Differential diagnosis

Usually, the diagnosis is straightforward, but occasionally other entities should be considered:

-

artifacts: air caught between structures outside the chest

-

the apparent pleural edge is denser (i.e. black) compared to a true pneumothorax which is a white pleural edge

may be seen extending beyond the chest cavity or seen to fade out

medial soft tissues of the arm

blankets

-

monitoring leads (although these should be obvious)

overlapping breast margin

normal anatomical structures, e.g. medial border of the scapula

giant bullous emphysema: differentiated from tension pneumothorax by clinical stability, interstitial vascular markings projected with the bullae and lack of hemithorax re-expansion following the insertion of an intercostal catheter

-

other gas in abnormal locations

other causes of a hyperlucent hemithorax

-

on CT

gas in a brachiocephalic vein from cannulation

beam-hardening artifact from concentrated iodinated contrast medium in a brachiocephalic vein or the SVC

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.