Stress fractures refer to fractures occurring in the bone due to a mismatch of bone strength and chronic mechanical stress placed upon the bone and form the most severe form of a stress response.

On this page:

Terminology

A pathological fracture, although a type of insufficiency fracture, is a term in general reserved for fractures occurring at the site of a focal bony abnormality. Some authors use the term stress fracture synonymously with fatigue fracture, and thus some caution with the term is suggested.

Epidemiology

Fatigue fractures are common in athletes, especially runners and military recruits. Insufficiency fractures occur more in women and older people 7,8.

Risk factors

The following conditions increase the risk of a stress injury 8:

female sex

low bone density

nutritional disorders or deficiencies

'female athlete triad'

long-distance running

inappropriately short recovery time

training changes

inadequate shoes

Clinical presentation

Stress fractures normally present with worsening pain with a history of minimal or no trauma. In the lower (weight-bearing) limb, there is often a history of a recent increase in physical activity or significant alteration in the type or duration of normal athletic activity.

Pathology

A stress fracture is the final stage of a stress injury and occurs if the bone fails to withstand a repetitive, cumulative loading force and is no longer capable of mitigating that loading stress with its healing capabilities and breaks 7.

Aetiology

fatigue fracture: abnormal stresses on normal bone

insufficiency fracture: normal stresses on abnormal bone

Location

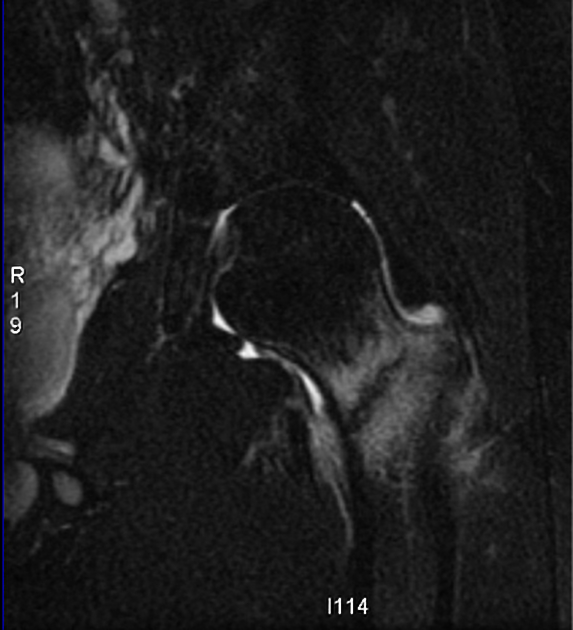

Stress fractures are far more common in the lower limb (~95%) than in the upper limb 5. High-risk sites of stress fractures are locations at greatest risk of a progression to complete fracture, displacement or non-union as these sites are under tensile stresses and have poor vascularity 9-11:

pars interarticularis of the lumbar spine

thigh and leg: femoral neck, patella, anterior tibial cortex

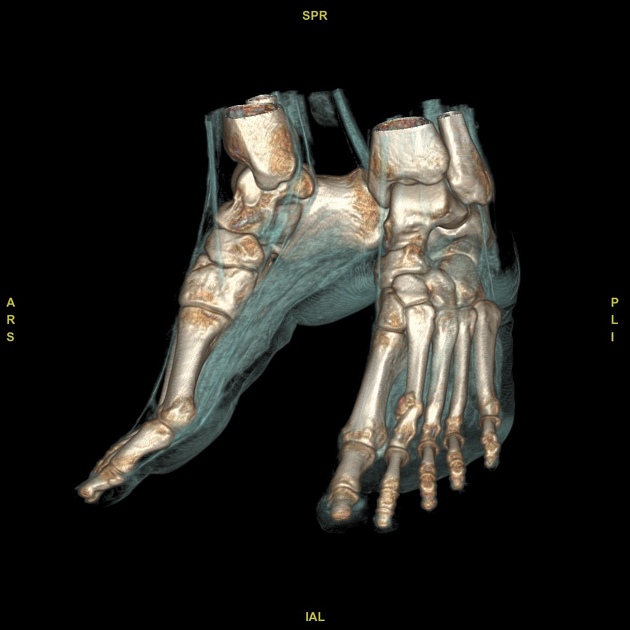

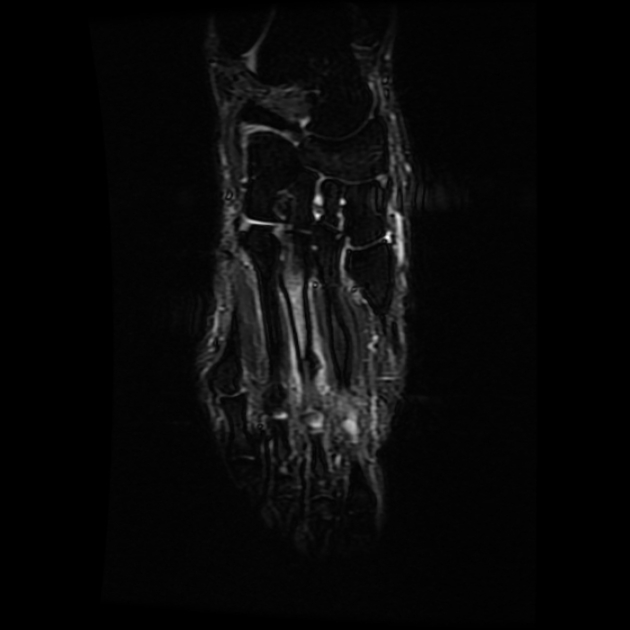

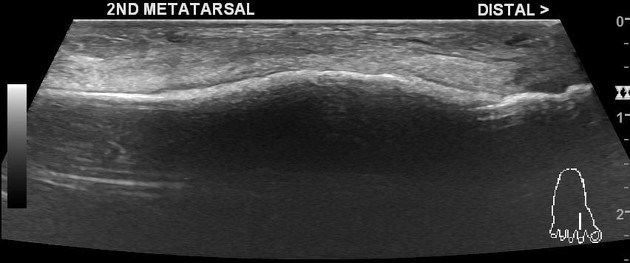

ankle and foot: medial malleolus, talus, navicular, 2nd to 4th metatarsal necks, 2nd metatarsal base, 5th metatarsal, hallux sesamoid

Low-risk sites of a stress fracture are at low risk of complications and are under compressive stresses 10,11:

ribs

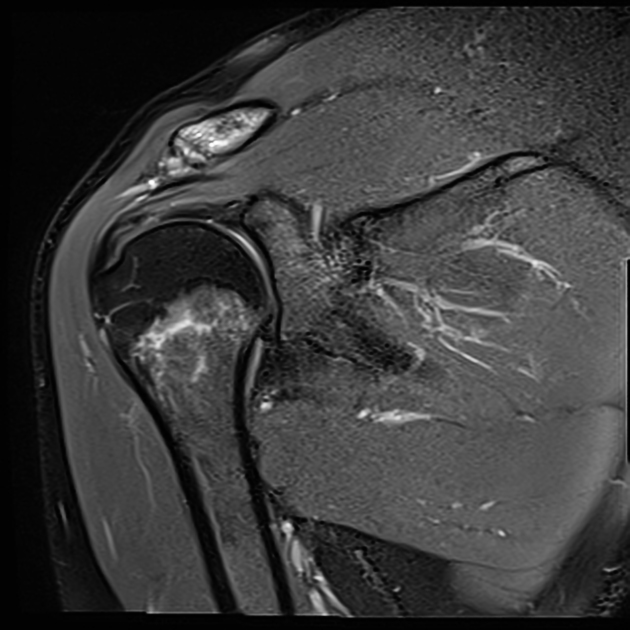

proximal humerus/humeral shaft

pelvis: sacrum, pubic rami

lower limb: calcaneus, posterior medial tibial shaft, fibula, lateral malleolus, 2nd to 4th metatarsal shafts

Radiographic features

Plain radiographs have poor sensitivity (15-35%) in early-stage injuries, which increases in late-stage injuries (30-70%), due to possible callus formation.

MRI is the most sensitive modality for diagnosis of a stress fracture and is an important tool to distinguish high and low-risk fractures to help clinicians with management plans and a sensitivity reported to reach close to 100% 5,6.

Plain radiograph

Plain radiographs have poor sensitivity in detecting stress fractures, as positive findings may take months to appear. During the first few weeks after the onset of symptoms, x-rays of the affected area may look normal.

Positive findings can include:

grey cortex sign: subtle loss of cortical density in early-stage stress injury

increasing sclerosis or cortical thickening along the fracture site

-

periosteal reaction/elevation

may take up to 2 weeks to be detectable

fracture line

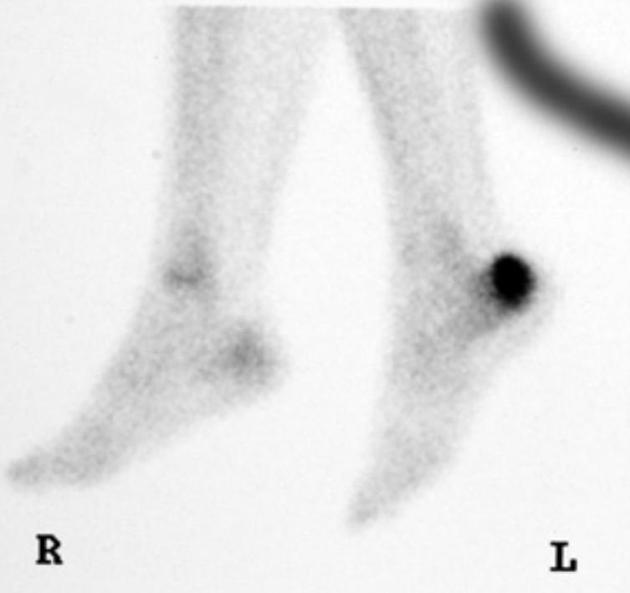

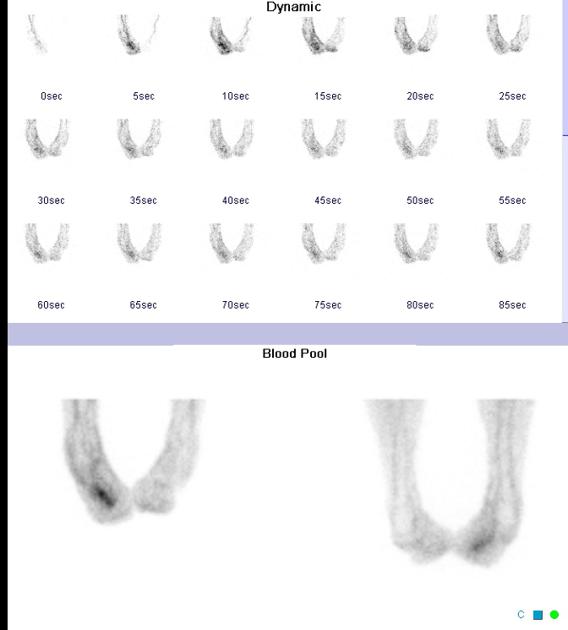

Nuclear medicine

Bone scans can show evidence of stress fracture within a few days of the onset of symptoms. As a modality, it is considered less sensitive than MRI 5.

Stress fractures on bone scintigraphy appear as foci of increased radioisotope activity ('hot spot') due to increased bone turnover at the site of new bone formation. However, as with all bone scintigraphy, this is non-specific; the increased uptake can also be due to osteomyelitis, bone tumours or avascular necrosis.

CT

The findings are similar to plain radiography, including sclerosis, new bone formation, periosteal reaction, and fracture lines in long bones.

CT may be useful in differentiating stress fractures from a bone tumour or osteomyelitis if the plain radiographs are negative and bone scans are positive.

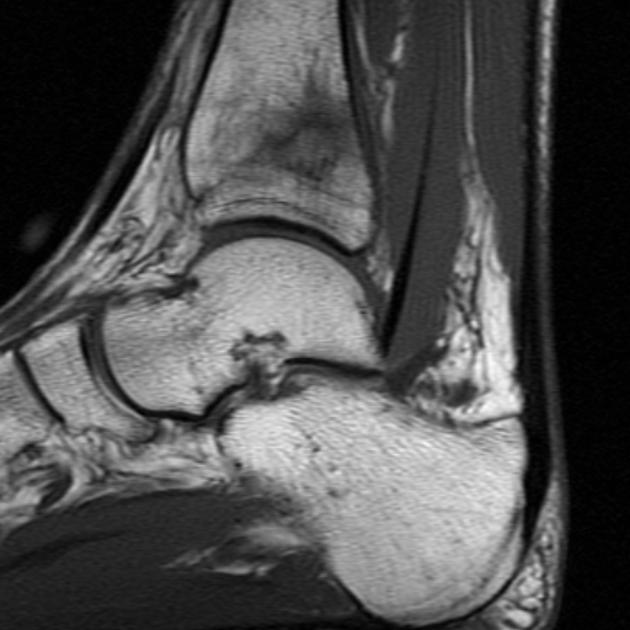

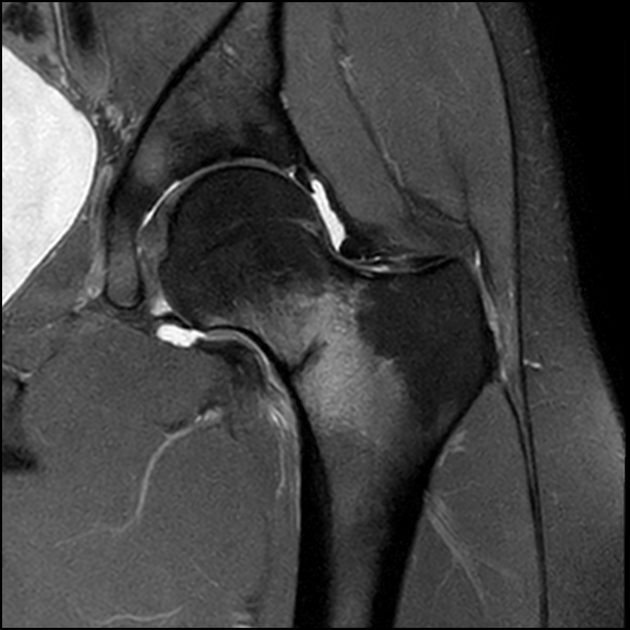

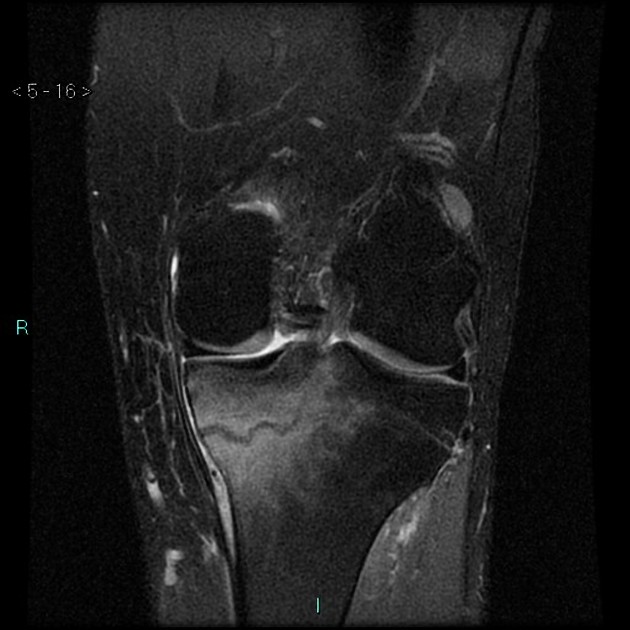

MRI

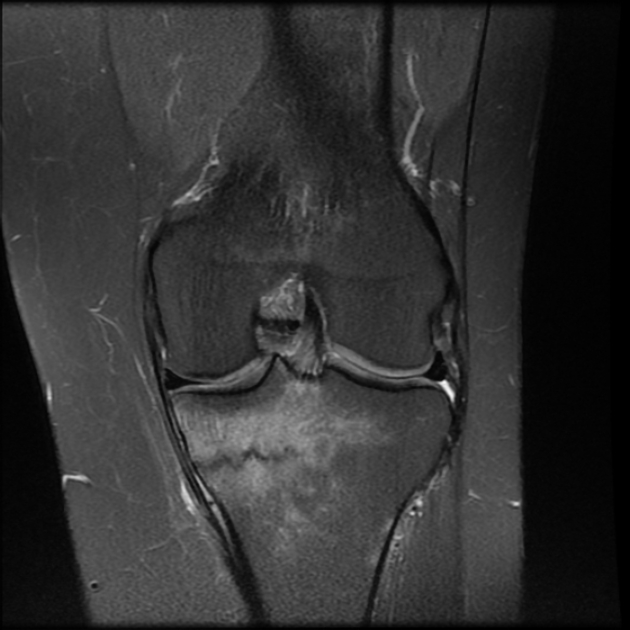

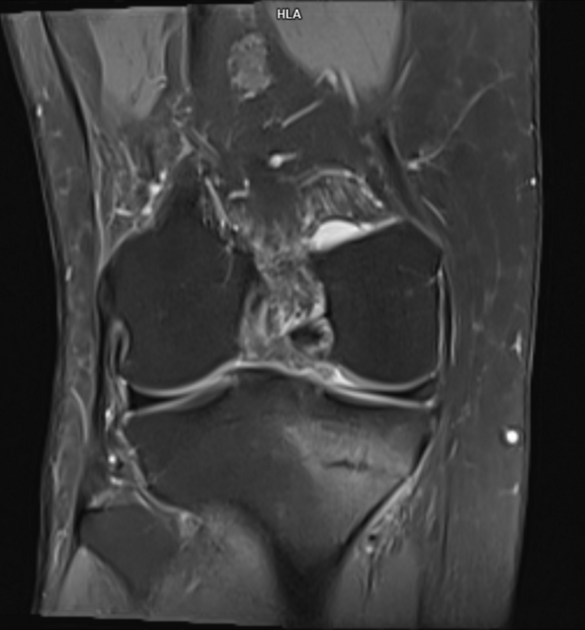

MRI is the most sensitive modality for detecting stress fracture, and may also be useful for differentiating ligamentous/cartilaginous injury from a bony injury.

Typical MRI appearance of stress fracture includes:

periosteal or adjacent soft tissue oedema

band-like bone marrow oedema

T1 hypointense fracture line evident in high-grade injury

The use of an MRI grading system for bone stress injuries helps predict recovery time (important, especially for athletes).

Treatment and prognosis

The site of the stress fracture and suitability for rehabilitation determines treatment.

Fractures at low-risk sites are managed conservatively with analgesia, ice, reduced weight-bearing and modification of activities until pain resolves.

At high-risk sites or in patients where long-term rehabilitation is detrimental to their livelihood (i.e. athletes or labourers), orthopaedic consultation is required.

Risk factors such as diet, vitamin D, and calcium should be addressed to prevent recurrence. Other factors, such as a gradual return to training and biomechanical evaluation of gait, may be required. Bone density evaluation can be considered in patients with recurrent stress fractures, a family history of osteoporosis, or stress fractures unexplained by exercise activity.

Differential diagnosis

osteosarcoma and bone tumours can also present with periosteal reaction

osteomyelitis has marrow oedema and soft tissue swelling

soft tissue bruise: has oedema at the injury site, but little marrow abnormality

osteoid osteoma: usually has a nidus <2 cm +/- surrounding sclerosis

Practical points

in addition to the risk stratification by location, any displacement or proximal femur fractures with a fracture line >50% of the width of the femoral neck should also be considered high-risk 6

calcaneal stress fractures are typically parallel to the posterior cortex

History

The first documented description of a metatarsal stress fracture is often credited to Sir Robert Jones, a British surgeon, in the early 20th century. However, the Prussian army and its medical personnel, including Dr. Friedrich Müller, are sometimes associated with early descriptions of stress fractures in soldiers during the First World War.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.