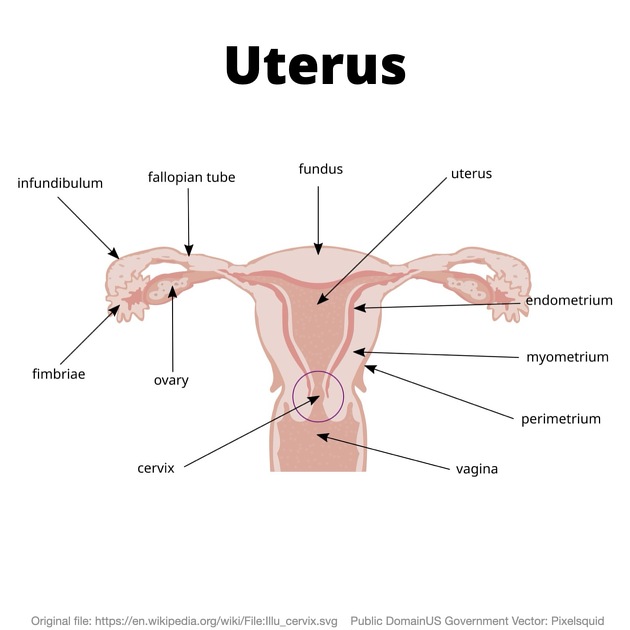

The uterus is an extraperitoneal hollow, thick-walled, muscular organ of the female reproductive tract that lies in the lesser pelvis.

On this page:

Gross anatomy

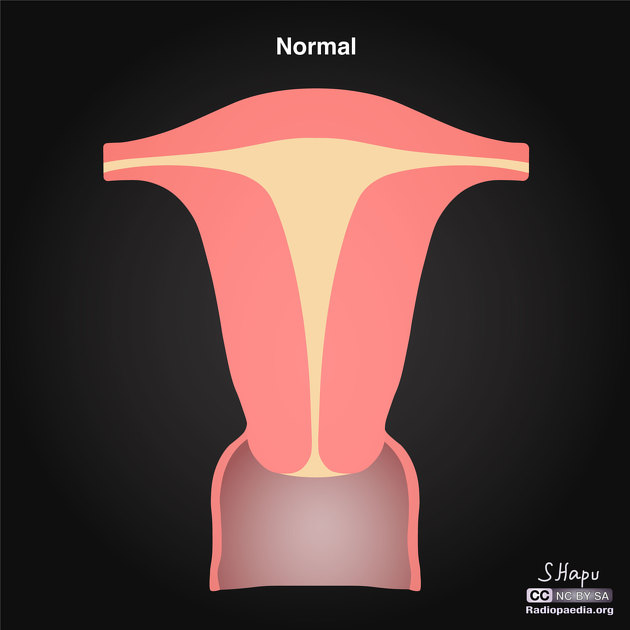

The uterus has an inverted pear shape. It measures about 7.5 cm in length, 5 cm wide at its upper part, and nearly 2.5 cm in thickness in adults. It weighs approximately 30-40 g.

The uterus is divisible into two portions: body and cervix. About midway between the apex and base is a slight constriction known as the isthmus. The portion above the isthmus is termed the body, and that below, the cervix. The part of the body which lies above a plane passing through the points of the entrance of the uterine tubes is known as the fundus.

The body gradually narrows from the fundus to the isthmus. The cavity of the body is a mere slit, flattened anteroposteriorly. It is triangular in shape:

the base being formed by the internal surface of the fundus between the orifices of the uterine tubes

the apex by the internal orifice of the uterus through which the cavity of the body communicates with the canal of the cervix

Although anatomically a part of the uterus, the uterine cervix has a different function and is associated with separate pathological entities. It is discussed in detail in a separate article.

Attachments

Musculotendinous and ligamentous

anterior: pubocervical ligament

lateral: transverse cervical ligaments (cardinal or Mackenrodt's)

posterior: uterosacral ligaments

inferior: puborectalis and pubovaginalis parts of the levator ani muscle

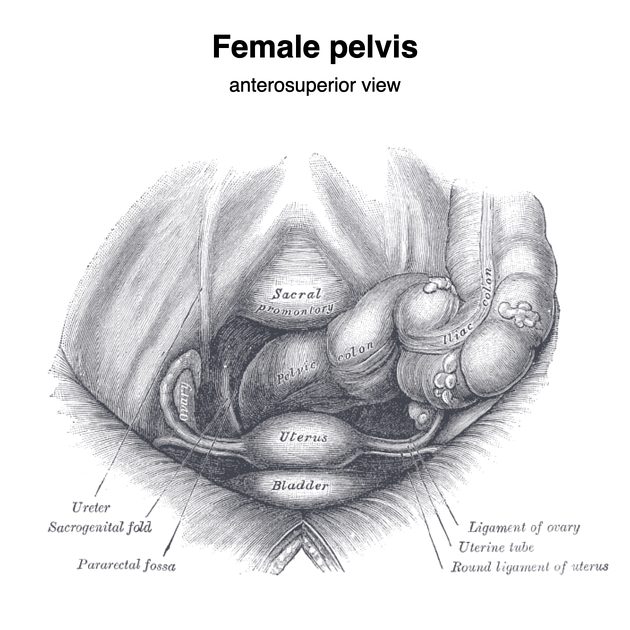

Relations

anteriorly: bladder; uterovesical pouch

posteriorly: rectum; pouch of Douglas

-

laterally: broad ligament; round ligament; uterine vessels

uterine tubes open into its upper part

inferiorly: uterine cavity communicates with that of the vagina

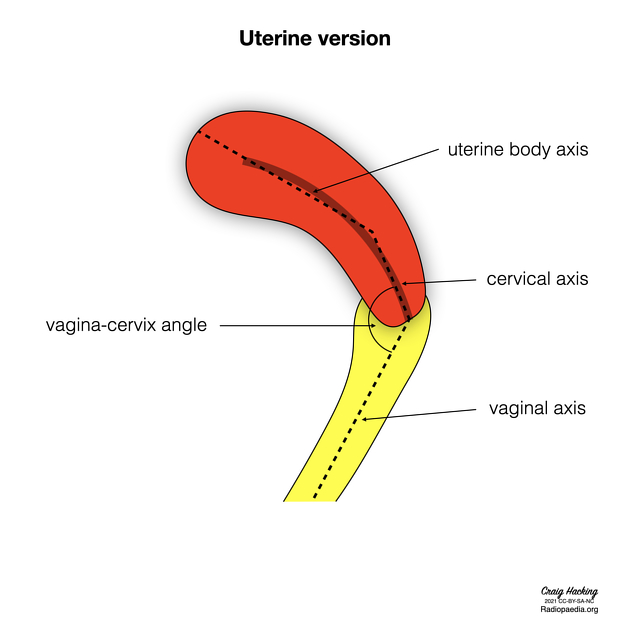

Position

Uterine position is adults is variable and largely depends on the degree of bladder and rectal distension. When the bladder is empty, the entire uterus is directed forward and is at the same time bent on itself at the junction of the body and cervix so that the body lies upon the bladder. As the latter fills, the uterus gradually becomes more and more erect until, with a fully distended bladder, the fundus may be directed back toward the sacrum.

The uterine position can be described in terms of version and flexion:

-

uterine version: defined as the angle that the cervical axis makes with the vaginal axis 8

-

anteversion

version angle <90° 8

external os points posteriorly towards the rectum 9

-

retroversion

version angle >90° 8

external os points superiorly towards the bladder 9

axial: external os points towards the introitus 9

-

-

uterine flexion: defined as the angle that the uterine body axis makes with the cervical axis 8

anteflexion: flexion angle <180° and the apex is directed anteriorly 8

retroflexion: flexion angle >180° and apeix is directed posteriorly 8

This results in a number of uterine positions:

anteverted anteflexed: cervix angles forward, body is flexed forward

Development

In the fetus, the uterus is contained in the abdominal cavity, projecting beyond the superior aperture of the pelvis. The cervix is considerably larger than the body.

At puberty, the uterus is pyriform in shape and weighs from 14-17 g. It has descended into the pelvis, the fundus being just below the level of the superior aperture of this cavity. The palmate folds are distinct and extend to the upper part of the cavity of the organ.

During menstruation, the uterus is enlarged, more vascular, and its surfaces rounder; the external orifice is rounded, its labia are swollen, and the lining membrane of the body thickened, softer, and of a darker colour.

During pregnancy, the uterus becomes enormously enlarged, and by the eighth month, it reaches the epigastric region. The increase in size is partly due to the growth of pre-existing muscles and partly to the development of new fibres.

After parturition, the uterus nearly regains its usual size, weighing about 42 g. Its cavity is larger than in the virgin state, its vessels are tortuous, and its muscular layers are more defined. The external orifice is more marked, and its edges present one or more fissures.

In old age, the uterus becomes atrophied and paler and denser in texture; a more distinct constriction separates the body and cervix. The internal orifice is frequently, and the external orifice is occasionally obliterated, while the lips almost entirely disappear.

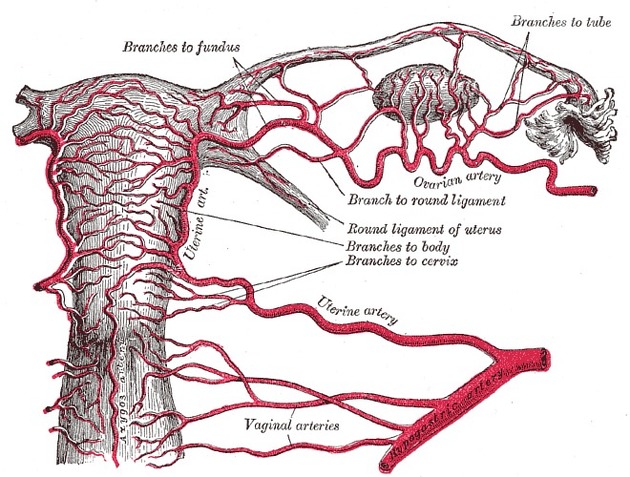

Arterial supply

-

uterine arteries and ovarian arteries

the terminations of the ovarian and uterine arteries unite and form an anastomotic trunk from which branches are given off to supply the uterus

in the impregnated uterus, the arteries carry the blood to the intervillous space of the placenta

Venous drainage

uterine vein draining into internal iliac vein

in the impregnated uterus, the veins convey blood away from the intervillous space of the placenta

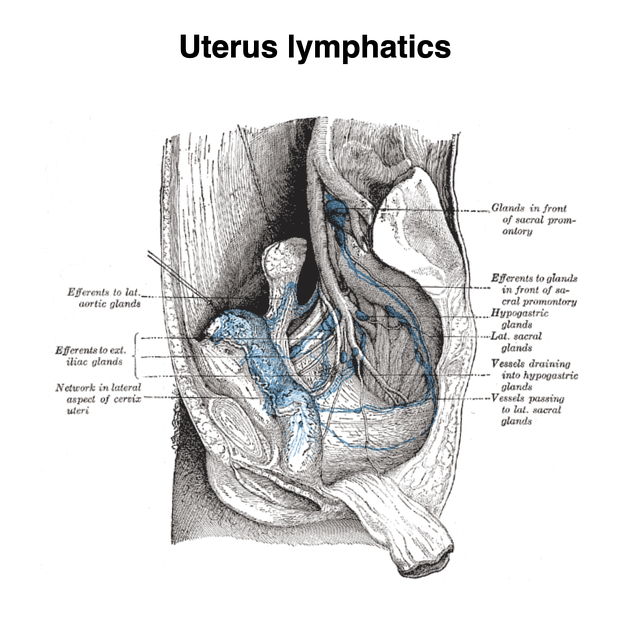

Lymphatic drainage

fundus: para-aortic nodes

body/cervix: internal and external iliac nodes; superficial inguinal nodes (via round ligament) 2

Innervation

The nerves are derived from the inferior hypogastric and ovarian plexuses (via the aorticorenal plexuses) from the third and fourth sacral nerves.

Variant anatomy

Radiographic features

Ultrasound is the primary diagnostic modality in characterising uterine lesions. Meanwhile, CT scan is normally done for other non-gynaecological indications. If there is indeterminate lesion found on ultrasound or CT, MRI is helpful in characterising the uterine lesions 7.

Fluoroscopy

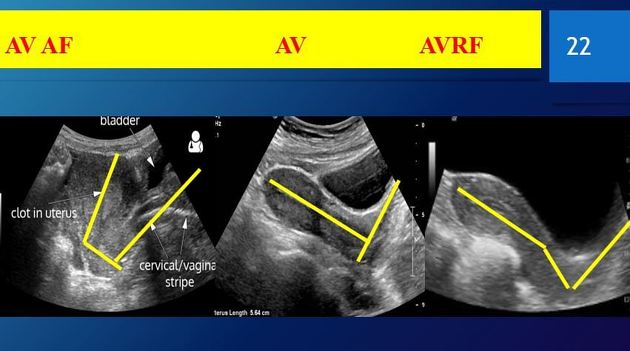

Ultrasound

The transabdominal US allows evaluation of the size and position of the uterus in the pelvic cavity. The transvaginal US allows the internal structure of the uterus to be examined 2.

CT

The uterus appears as a homogeneous soft tissue mass posterior to the bladder. The myometrium shows low density on unenhanced CT with the endometrial canal showing even lower density than myometrium 7. It normally enhances post intravenous contrast 2. There are generally three types of enhancement in a normal uterus 7:

type 1: thick or thin sub-endometrial enhancement, most commonly found in pre-menopausal women

type 2: diffuse myometrial enhancement, found in both pre and post-menopausal women

type 3: faint diffuse myometrial enhancement, exclusively found in post-menopausal women

There is also a possibility of patchy enhancement of the uterus. These variable enhancement patterns could be due to differences in age, parity and menstrual status. Basal layer of endometrium adjacent to the myometrium could contribute to thin sub-endometrial enhancement. Thick sub-endometrial enhancement could be due to the junctional zone. Meanwhile, diffuse myometrial enhancement could be due to the density of smooth muscles and blood vessels in the myometrium that affects the uptake of contrast 7.

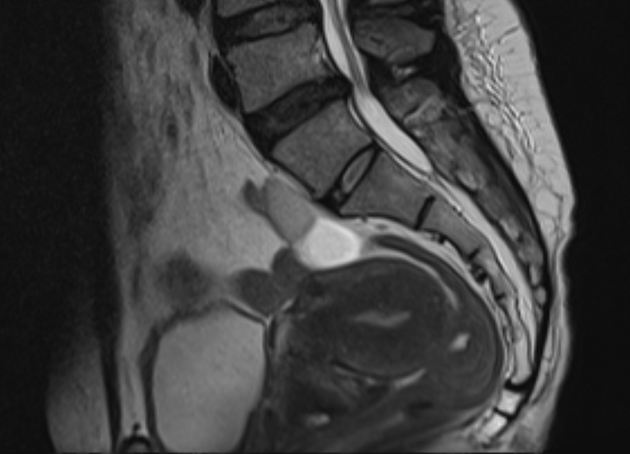

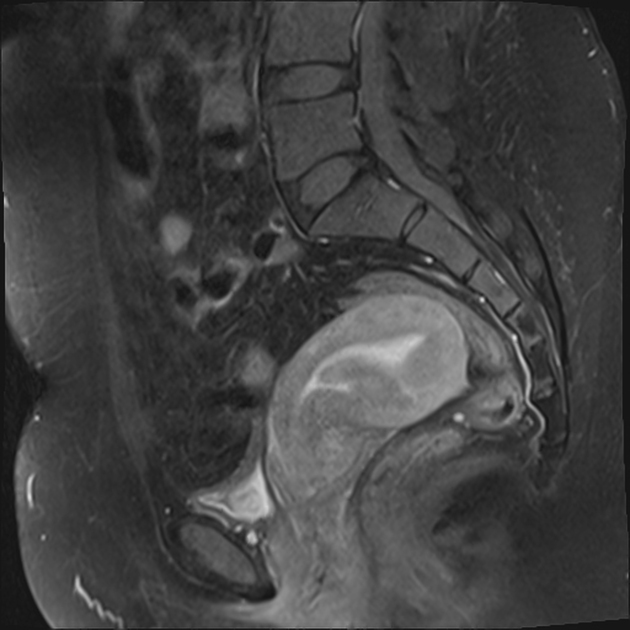

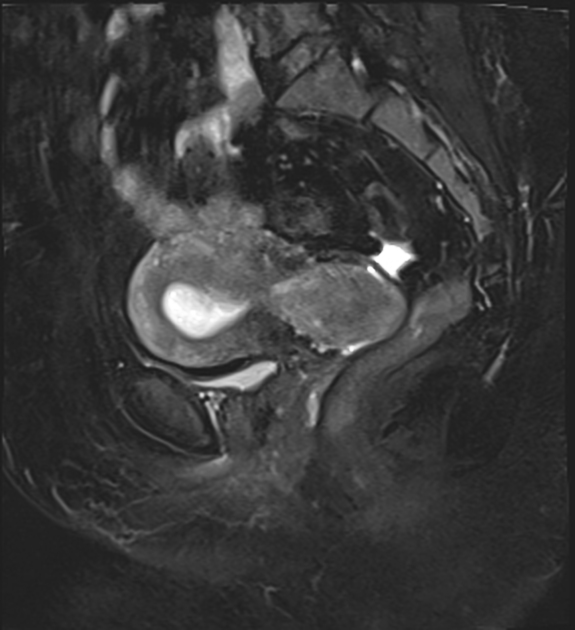

MRI

MRI displays the zonal anatomy of the uterus. The myometrial layers are indistinguishable on T1 imaging. It can be divided into three zones on T2 weighted imaging 7:

high T2 signal of endometrium

low T2 signal of inner myometrium, known as the junctional zone

intermediate T2 signal of the outer myometrium

On contrasted MRI study, myometrium shows homogenous hyperintensity on arterial and venous phases. Meanwhile, endometrium enhances slowly and is more hypointense when compared to myometrium 7.

There is some physiologic variability to the myometrial zonal appearance. The junctional zone is less distinct pre-menarche and during pregnancy 4. In the postmenopausal patient, the outer myometrium is thinner and of lower signal due to reduced fluid content and therefore approximates the junctional zone, with poor delineation of the margin in some patients.

Myometrial zonal anatomy has diagnostic implications in the assessment of adenomyosis and in the staging of endometrial carcinoma, where the depth of myoinvasion is assessed in relation to the junctional zone.

Endometrium on MRI undergoes expected physiological variation in thickness, but the structural, cyclical changes seen on ultrasound are not reproduced.

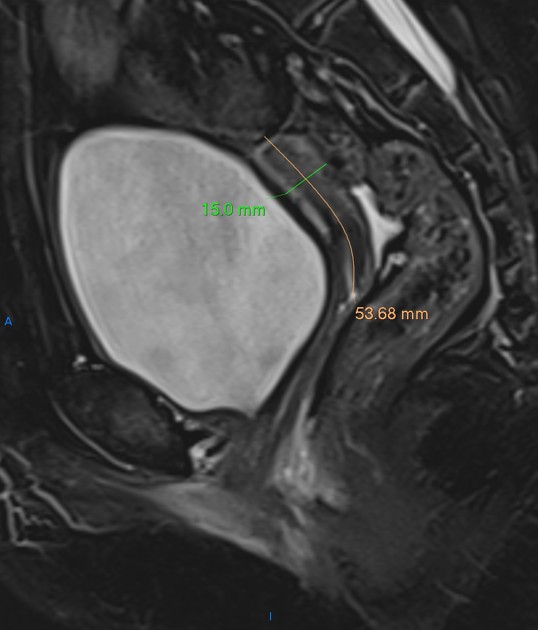

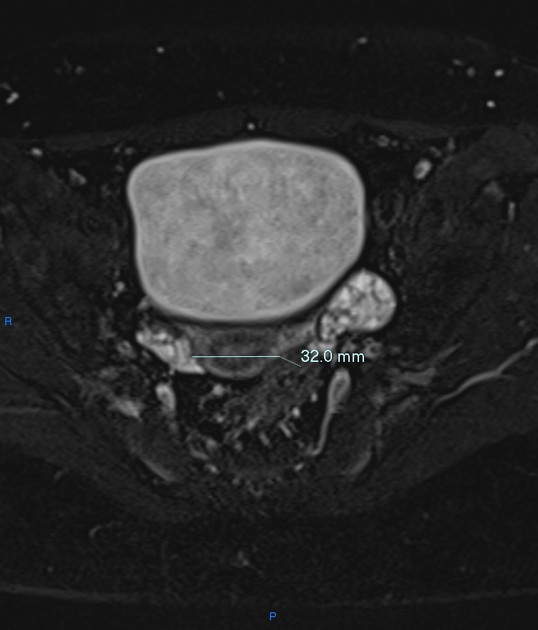

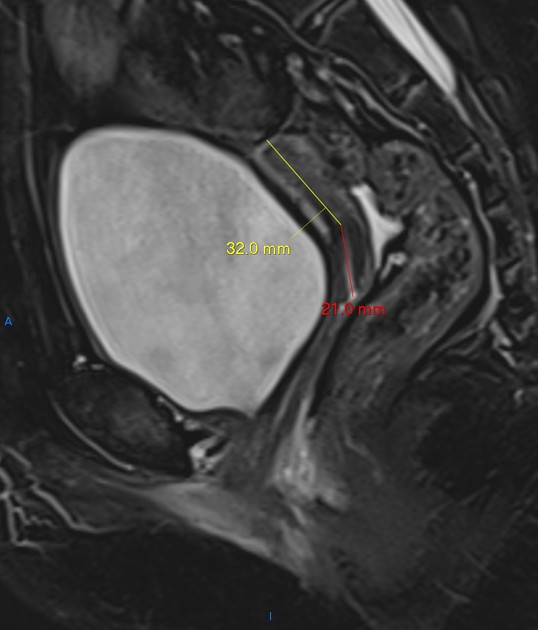

Imaging assessment of the uterine size

The uterine length is measured in the midsagittal plane from the outer serosal surface of the fundus to the external cervical os. The uterine height (AP) is measured in the midsagittal plane anteroposteriorly from outer to outer serosal surfaces. The uterine width is measured in the transverse plane. The uterine body length is measured in the midsagittal plane from the fundal outer serosal surface to the internal os. The uterine cervix length is measured in the midsagittal plane from the internal os to the external os.

Several methods in the assessment of the uterine size are present in the literature:

Uterine volume measurement 5: using the formula; Length x Width x Height x 0.523

According to this method, normal mean uterine volumes are as follows:

0-1 month: 3.4 mL

3 months: 0.9 mL

1-5 years: 1 mL

7 years: 0.9 mL

9 years: 1.3 mL

11 years: 1.9 mL

13 years: 11 mL

15 years: 21.2 mL

Uterine length and uterine body to cervix ratio by life stage 6 :

neonatal: length 3.5 cm, body to cervix ratio 1:2

paediatric: length 1-3 cm, body to cervix ratio 1:1

prepubertal: length 3-4.5 cm, body to cervix ratio 1-1.5: 1

pubertal: length 5-8 cm, body to cervix ratio 1.5-2:1

reproductive: length 8-9 cm, body to cervix ratio 2:1

postmenopausal: length 3.5-7.5 cm, body to cervix ratio 1-1.5:1

Related pathology

-

gamuts

-

neoplastic

-

infections

-

others

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.