Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that predominantly affects the colon and has extraintestinal manifestations.

On this page:

Epidemiology

Typically ulcerative colitis manifests in young adults (15-40 years of age) and is more prevalent in males but the onset of disease after the age of 50 is also common 1,3,5.

Ulcerative colitis is less prevalent in smokers than in non-smokers.

Associations

-

primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)

-

70-80% of patients with PSC develop inflammatory bowel disease

87% of these develop ulcerative colitis

-

primary biliary cholangitis: rare 20,21

coeliac disease: 3x increased risk 17

Clinical presentation

Clinically patients have chronic diarrhoea (sometimes bloody) associated with tenesmus, pain, and fever 1. C-reactive protein levels are usually normal 6.

Pathology

Environmental and genetic factors are thought to play a role in the pathogenesis, although the condition remains idiopathic.

Unlike Crohn disease which is characteristically a transmural disease, ulcerative colitis is usually limited to the mucosa and submucosa 5.

The diagnosis is often made with endoscopy, allowing biopsy of any suspicious areas.

Extraintestinal manifestations

thrombotic complications

hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (rare) 19

Severity scoring systems

Several severity scoring systems exist. These include:

Mayo score

One of the most commonly used scoring systems. It is a composite of subscores from four categories, namely stool frequency, rectal bleeding, findings of flexible proctosigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy and physician’s global assessment. Total score ranges from 0-12 8.

Endoscopic component ranges from 0-3

0: normal mucosa or inactive disease

1: mild disease with evidence of mild friability, reduced vascular pattern, and mucosal erythema

2: moderate disease with friability, erosions, complete loss of vascular pattern, and significant erythema

3: ulceration and spontaneous bleeding

Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS)

A newer endoscopic scoring system includes assessment of vascular pattern, bleeding, and ulcers and excludes mucosal friability. In this system,

The vascular pattern is rated as 1-3

1: normal

2: patchy loss of vascular pattern

3: complete loss of vascular pattern

Bleeding is characterised from 1-4

1: none

2: mucosal bleeding

3: mild colonic luminal bleeding

4: moderate or severe luminal bleeding

Erosions and ulcers are characterised from 1-4

1: none

2: erosions

3: superficial ulceration

4: deep ulcers

Other classification systems include (used for inflammatory bowel disease in general)

Radiographic features

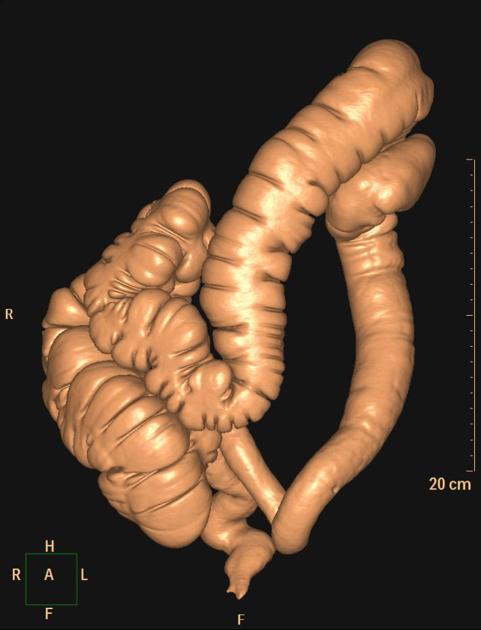

Involvement of the rectum is almost always present (95%) 1, with the disease involving a variable length of the most distal colon, in continuity. The entire colon may be involved, in which case oedema of the terminal ileum may also be present (so-called backwash ileitis).

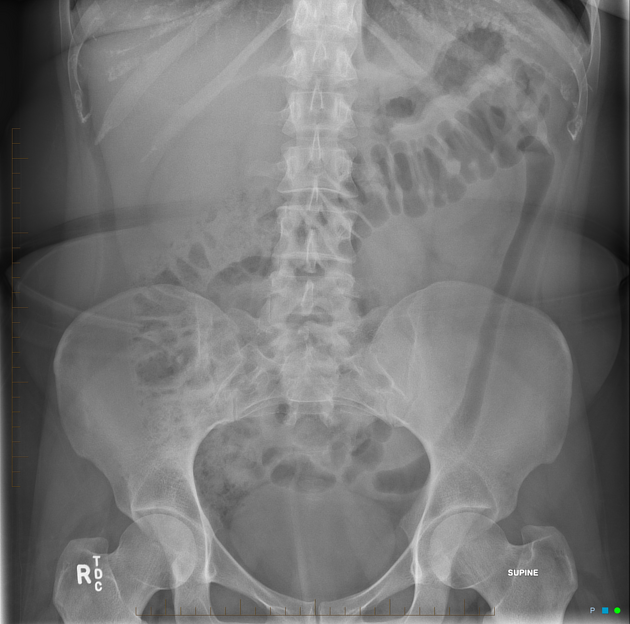

In very severe cases, the colon becomes atonic, with marked dilatation, worsened by bacterial overgrowth. This leads to toxic megacolon, which although uncommon, has a poor prognosis 13.

Plain radiograph

Non-specific findings, but may show evidence of mural thickening (more common), with thumbprinting also seen in more severe cases.

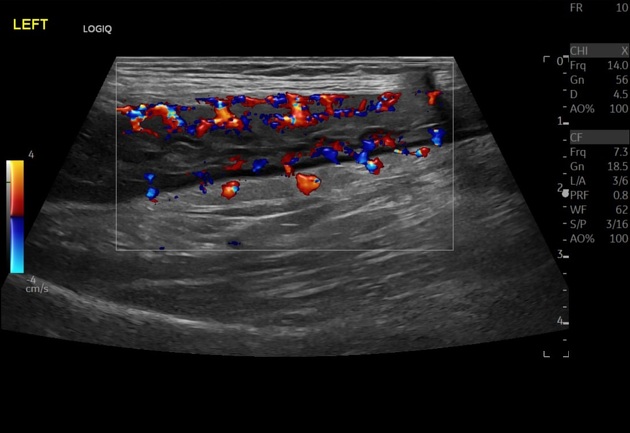

Ultrasound

Good sensitivity and specificity in detecting active disease when bowel wall thickness is >3-4 mm in the right and transverse colon. Its performance improves when associated with the detection of a Doppler signal 22.

The accuracy is decreased for the rectum, due to the rectum’s deep position in the pelvis 22.

Fluoroscopy

Double-contrast barium enema allows for exquisite detail of the colonic mucosa and also allows the bowel proximal to strictures to be assessed. It is however contraindicated if acute severe colitis is present due to the risk of perforation.

Mucosal inflammation leads to a granular appearance on the surface of the bowel. As inflammation increases, the bowel wall and haustra thicken.

Mucosal ulcers are undermined (button-shaped ulcers). When most of the mucosa has been lost, islands of mucosa remain giving it a pseudopolyp appearance.

In chronic cases, the bowel becomes featureless with the loss of normal haustral markings, luminal narrowing, and bowel shortening (lead pipe sign).

Small islands of residual mucosa can grow into thin worm-like structures (so-called filiform polyps)

Colorectal carcinoma in the setting of ulcerative colitis is more frequently sessile and may appear to be a simple stricture.

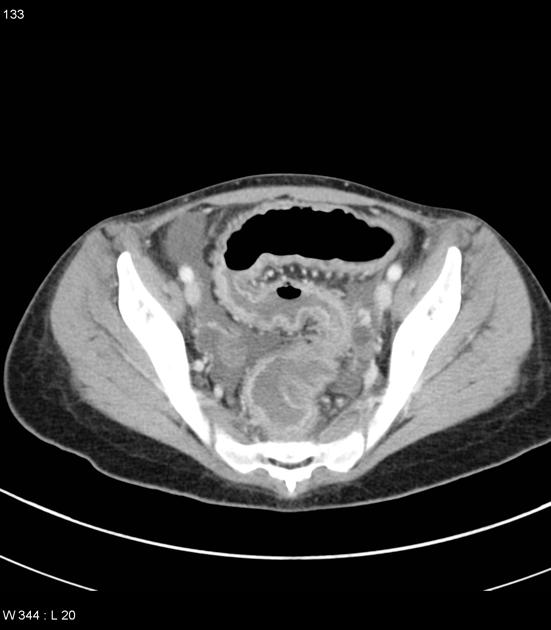

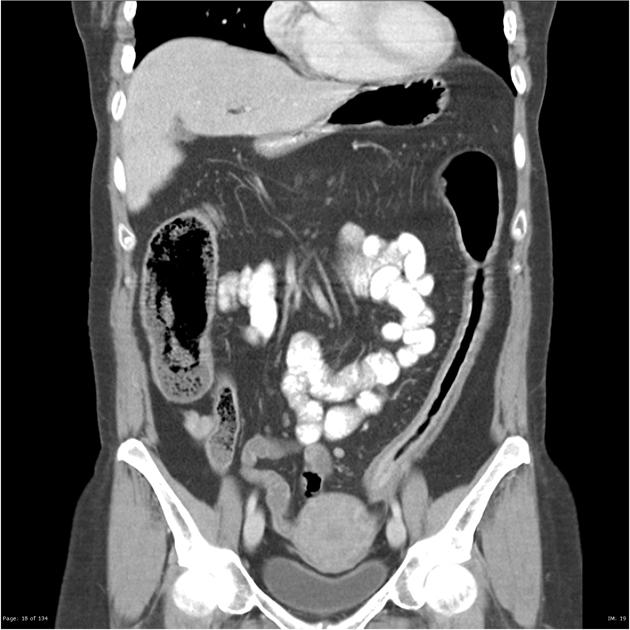

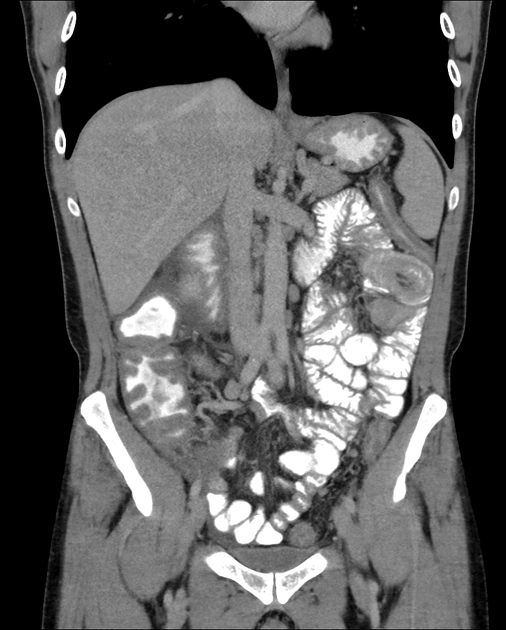

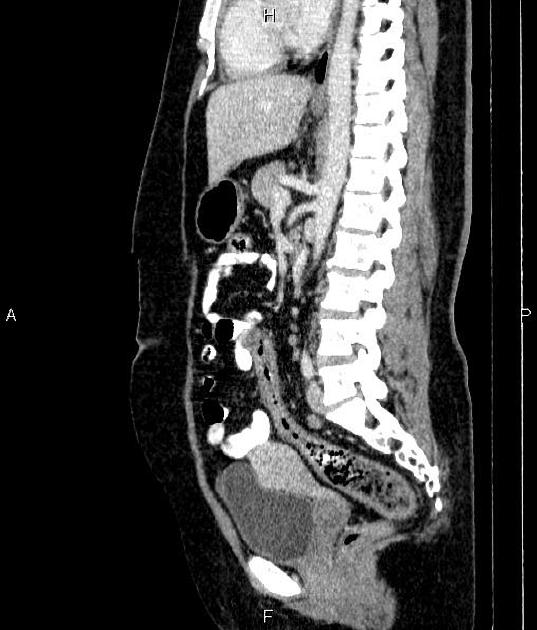

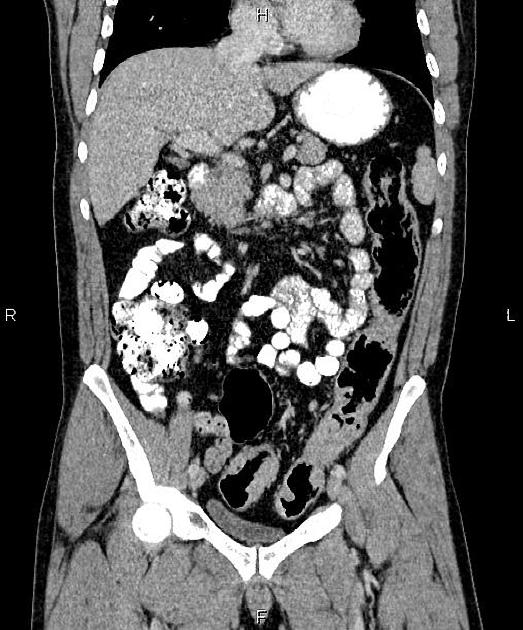

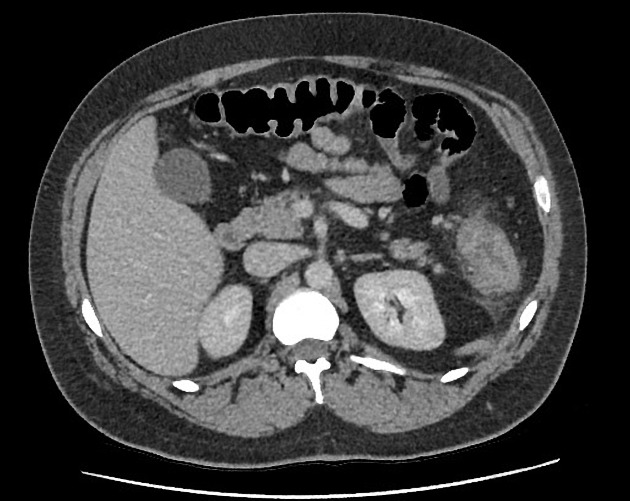

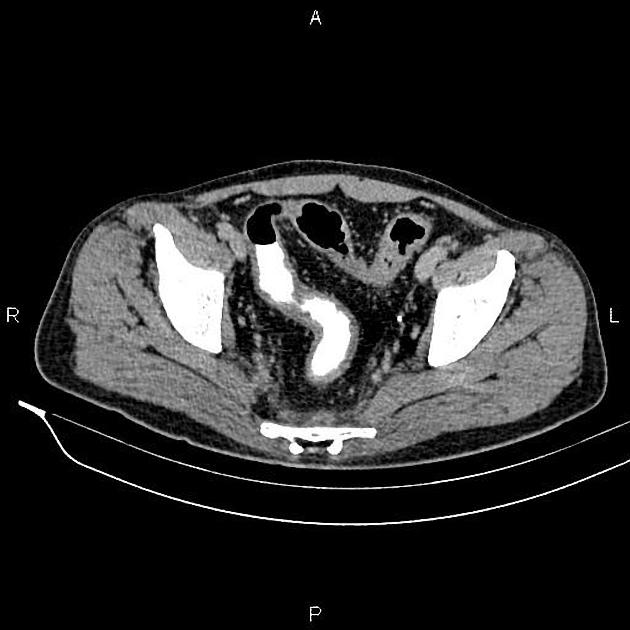

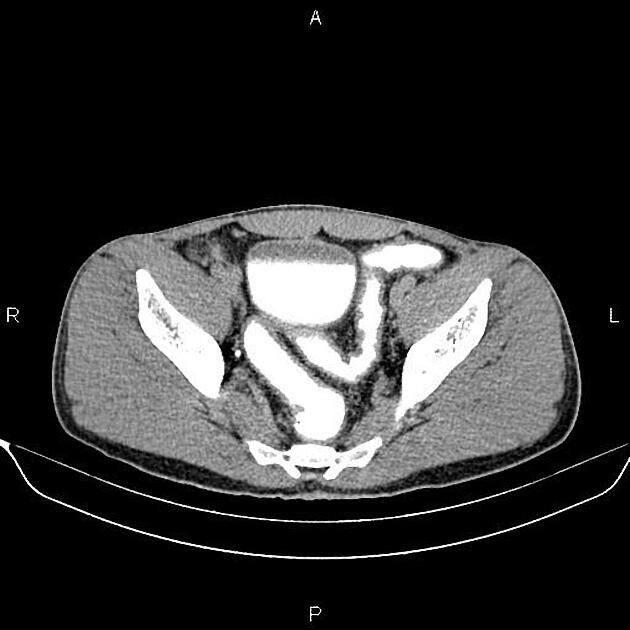

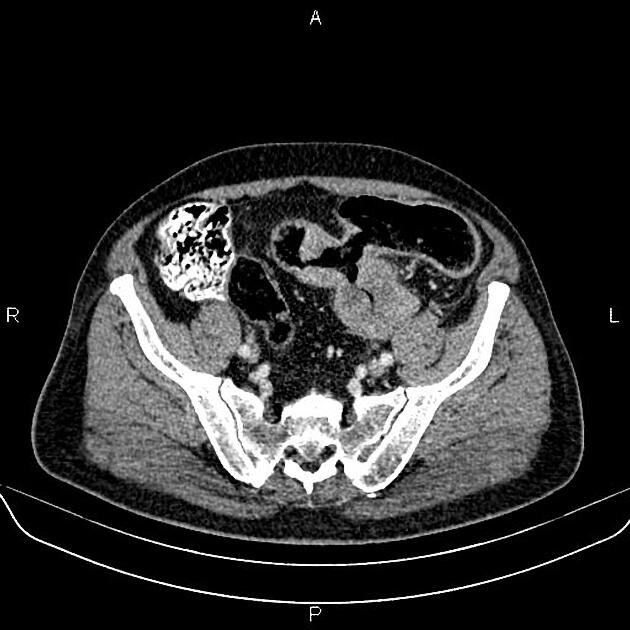

CT

CT will reflect the same changes that are seen with a barium enema, with the additional advantage of being able to directly visualise the colonic wall, and the terminal ileum and identify extracolonic complications, such as perforation or abscess formation. It is important to note however that CT is insensitive to early mucosal disease 2.

Inflammatory pseudopolyps may be seen if large enough, in well-distended bowel. In areas of mucosal denudation, abnormal thinning of the bowel may also be evident 2.

A cross-section of the inflamed and thickened bowel has a target appearance due to concentric rings of varying attenuation, also known as mural stratification 1,2.

In chronic cases, submucosal fat deposition is seen, particularly in the rectum (fat halo sign). Also in this region, extramural deposition of fat leads to thickening of the perirectal fat and widening of the presacral space 1,2.

Strictures are also common and are not all malignant. These are predominantly due to marked muscularis mucosae hypertrophy, which is also in part responsible for the lead pipe sign.

Colorectal carcinoma is often sessile. Focal loss of mural stratification or excessive mural thickness (1.5 cm) should prompt endoscopic evaluation 2.

Some segments of the bowel may show pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis in some cases 10.

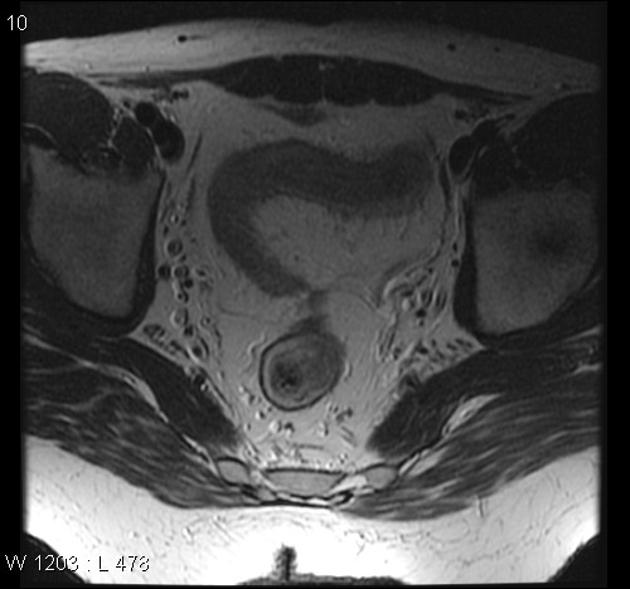

MRI

The current status of MRI in ulcerative colitis is that of a promising, non-invasive technique for imaging the extent of more severe disease.

The most striking abnormalities in ulcerative colitis are colonic wall thickening and increased enhancement.

The median wall thickness in ulcerative colitis ranges from approximately 4.5 to 10 mm. In general, the more severe the inflammation, the thicker the colonic wall. A colonic wall thickness <3 mm is usually considered as normal, 3-4 mm as a "grey zone," and >4 mm as pathological.

The use of diffusion-weighted imaging in the assessment of ulcerative colitis has been encouraging. One study, which compared the MRI with endoscopy, found that a b value of 800 s/mm2 was most accurate (cf. 400, 600 or 1000 s/mm2) at diagnosing active colitis, with a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 79% 9.

Enhancement of the mucosa with absent or decreased enhancement of the submucosa produces a low signal intensity stripe - the so-called submucosal stripe.

Other features are the loss of haustral markings, backwash ileitis, mild enhancement with no wall thickening, and increased signal intensity of the pericolonic fat.

Treatment and prognosis

Total colectomy is curative of both the intestinal symptoms and the potential risk of colorectal carcinoma. Medical therapy such as corticosteroids 18 is able to control colonic disease in some cases but does not remove the need for regular screening for malignancy.

Due to close surveillance patients with ulcerative colitis have a normal or even slightly improved survival compared to the normal population 3. This is clearly not the case if the disease is not diagnosed or treatment is not available.

Complications

chronic disease is associated with a significantly elevated malignancy risk, of up to 0.5-1.0% per year after 10 years of the disease ref

10-15% of cases initially presenting as ulcerative colitis later progress to Crohn disease ref

patients with ulcerative colitis may have a higher incidence of perianal disease than the general population 11

lower gastrointestinal tract haemorrhage

increased risk of thromboembolism 14

Differential diagnosis

The most important differential diagnosis is Crohn disease (see Crohn disease vs ulcerative colitis). Otherwise, the differential includes other causes of colitis:

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.