Congenital tracheo-esophageal fistula is a congenital pathological communication between the trachea and esophagus.

On this page:

Epidemiology

Tracheo-esophageal fistula and esophageal atresia have a combined incidence of approximately 1 in 3500 live births 1-3,5. There is only a minimal hereditary/genetic component with an incidence in twins and those with family history being only approximately 1% 5. There is no convincing gender or racial predilection 5.

Associations

In just over half of cases, there are other associated congenital abnormalities, including 1,2,5:

-

cardiac anomalies (15-19%) 1-3

-

gastrointestinal anomalies (22%)

-

aneuploidic chromosomal abnormalities

-

non-aneuploidic syndromic associations 5

Clinical presentation

Clinical presentation is similar for all types except for type E (H-type).

Antenatally polyhydramnios may be present due to inability to adequately swallow fluid, and it is found in up to 90% of cases 1, but is, unfortunately, a non-specific sign.

The diagnosis is usually made in the neonate, as they experience feeding difficulties and respiratory compromise due to repeated aspiration. In cases where esophageal atresia is present (i.e. all but H-type), attempts at passing a nasogastric tube will not be successful. Only with H-type fistulae, which can be very small and typically slant down from the trachea toward the esophagus, presentation may be delayed, sometimes for many years 2.

Pathology

The trachea is an out-budding from the ventral foregut, and tracheo-esophageal fistulae represent incomplete/abnormal division. They are very closely related to esophageal atresia, and represent a spectrum of disease. As such, the types of esophageal atresia / tracheo-esophageal fistula can be divided into 1,2:

type A: isolated esophageal atresia (8%)

type B: proximal fistula with distal atresia (1%)

type C: proximal atresia with distal fistula (85% - most common)

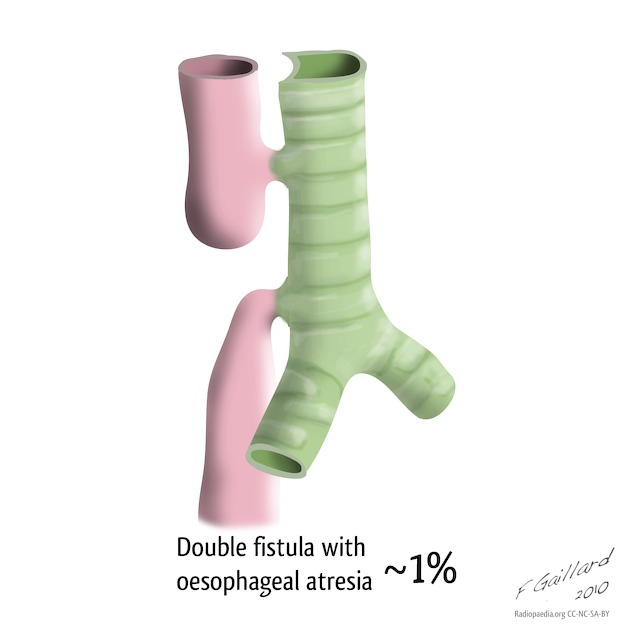

type D: double fistula with intervening atresia (1%)

type E: isolated fistula (H-type) (4%)

See: esophageal atresia classification.

Radiographic features

Plain radiograph

Demonstration of the nasogastric tube curled in the proximal esophagus in a child where the passage of the tube has been unsuccessful is usually sufficient for diagnosis. The proximal esophageal stump may be distended with air (types A and C).

The presence of air in the stomach and bowel in the setting of esophageal atresia implies that there is a distal fistula.

Often the lungs demonstrate areas of consolidation/atelectasis due to recurrent aspiration.

Fluoroscopy

H-type fistulas can be difficult to diagnose and may require contrast swallow studies, looking for contrast passing into the tracheobronchial tree.

Barium is usually the contrast medium of choice, a non-ionic iodinated contrast medium can be used alternatively. Ionic iodinated contrast medium should not be used as they can cause chemical pneumonitis 6.

Ultrasound

Antenatal ultrasound may demonstrate polyhydramnios or even in some cases a distended proximal blind-ending esophagus 1.

CT

In some instances, CT and virtual bronchoscopy may be of benefit in preoperative planning 4. This is especially the case in patients with long segment atresia who may require a staged operation.

Treatment and prognosis

Prior to surgical correction, bronchoscopy is frequently performed. In infants who are deemed unable to tolerate emergency repair, a gastrostomy and sump drainage catheter may be performed to allow feeding and weight gain. Another reason for a delay is in patients who have a "long-gap" atresia precluding primary anastomosis repair. In most cases, however, the defect is corrected immediately.

Prognosis is often most affected by the presence of associated congenital anomalies. For example in one study (albeit from 1979) the mortality for infants with just esophageal atresia / tracheo-esophageal fistula was 23% vs 79% in those with associated cardiac anomalies 3.

Differential diagnosis

In an older patient consider an:

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.