Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS) refers to the idiopathic thickening of gastric pyloric musculature which then results in progressive gastric outlet obstruction.

On this page:

Epidemiology

Pyloric stenosis is relatively common, with an incidence of approximately 2-5 per 1000 births, and a male predilection (M:F ~4:1). It is more commonly seen in the White population 4 and is less common in India and among Black and other Asian populations.

Risk factors

being firstborn

maternal history of pyloric stenosis 10

cesarean section delivery

bottle feeding 12

exposure to macrolide antibiotics 16

Associations

Clinical presentation

While symptoms may start as early as 3 weeks, it typically clinically manifests between 6 to 12 weeks of age. Clinical presentation is typical with non-bilious projectile vomiting. The hypertrophied pylorus can be palpated as an olive-sized mass in the right upper quadrant. A succussion splash may be audible, and although common, is only relevant if heard hours after the last meal 6. Due to the loss of hydrochloric acid in the gastric contents from persistent vomiting, patients are at risk of electrolyte imbalance, specifically the characteristic hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis. In severe cases of dehydration a paradoxical aciduria may develop, as the kidneys retain sodium ions and water in exchange for urinary excretion of hydrogen ions.

Pathology

Pyloric stenosis is the result of both hyperplasia and hypertrophy of the pyloric circular muscle fibers. The pathogenesis of this is not understood. There are four main theories 9:

immunohistochemical abnormalities

genetic abnormalities

infectious cause

hyperacidity theory

Radiographic features

Plain radiograph

Abdominal x-ray findings are non-specific but may show a distended stomach with minimal distal intestinal bowel gas.

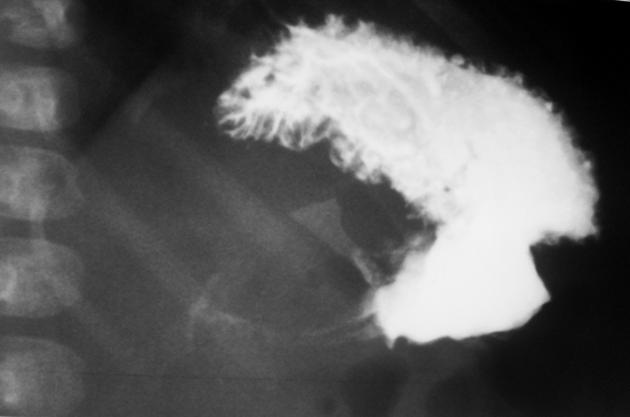

Fluoroscopy

An upper gastrointestinal series (barium meal) excludes other, more serious causes of pathology, but the findings of an upper gastrointestinal series infer, rather than directly visualize, the hypertrophied muscle. On upper gastrointestinal fluoroscopy:

delayed gastric emptying

peristaltic waves (caterpillar sign)

elongated pylorus with a narrow lumen (string sign) which may appear duplicated due to puckering of the mucosa (double-track sign)

the pylorus indents the contrast-filled antrum (shoulder sign) and (tit sign) or base of the duodenal bulb (mushroom sign)

the entrance to the pylorus may be beak-shaped (beak sign)

Ultrasound

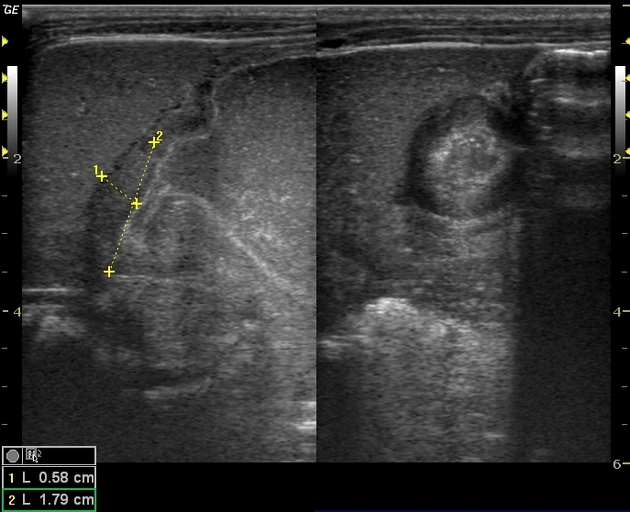

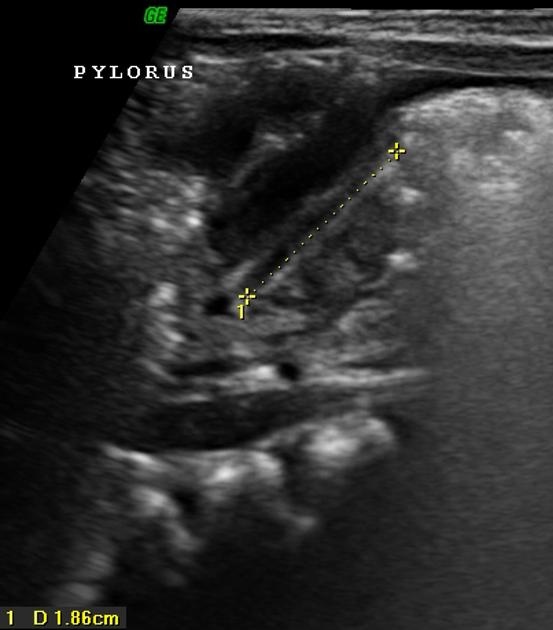

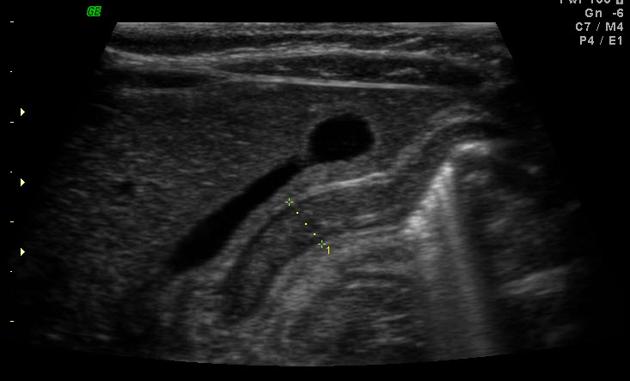

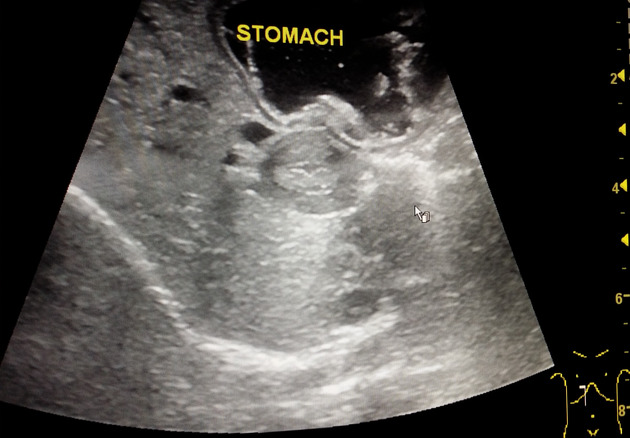

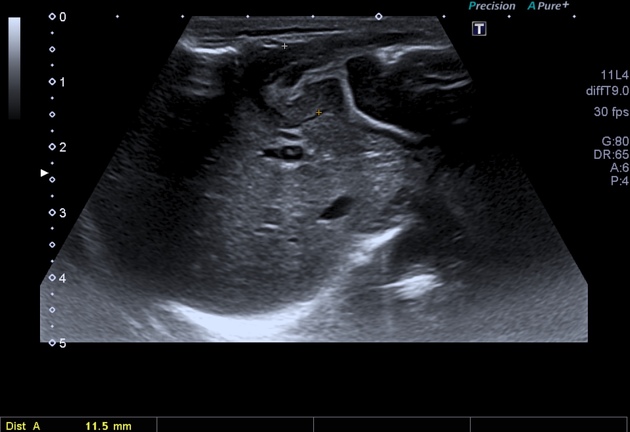

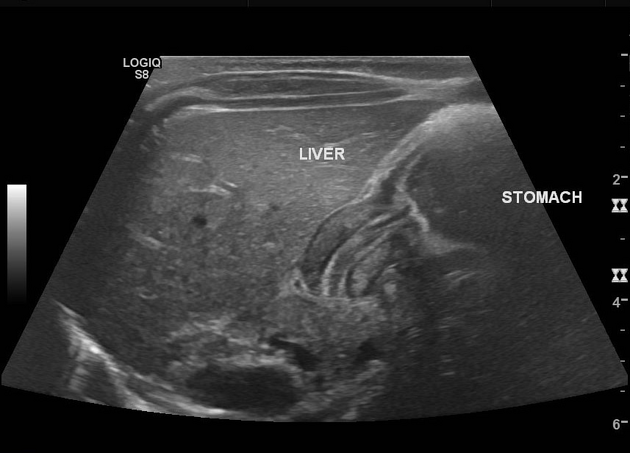

Ultrasound is the modality of choice in the right clinical setting with a sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 100% 15. Advantages over a barium meal include direct visualization of the pyloric muscle and avoiding exposure to ionizing radiation. Unfortunately, it is incapable of excluding other diagnoses such as midgut volvulus. A helpful ultrasound technique is to locate the gallbladder, then turn the probe obliquely sagittal to the body in an attempt to identify the pylorus longitudinally 7.

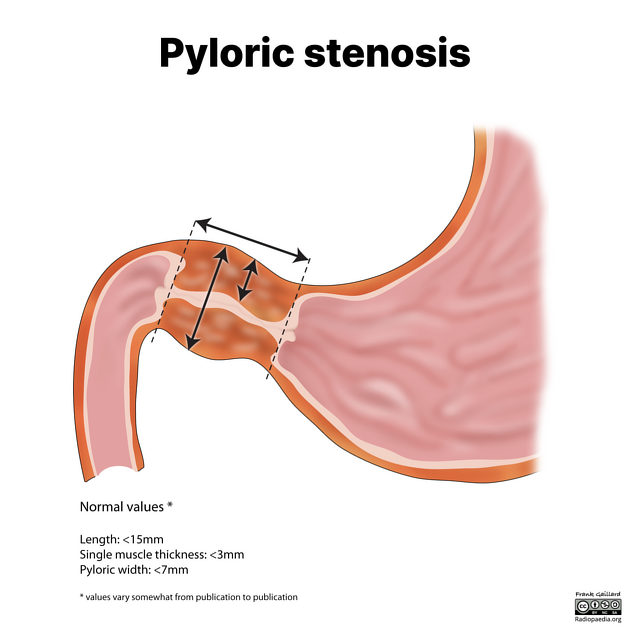

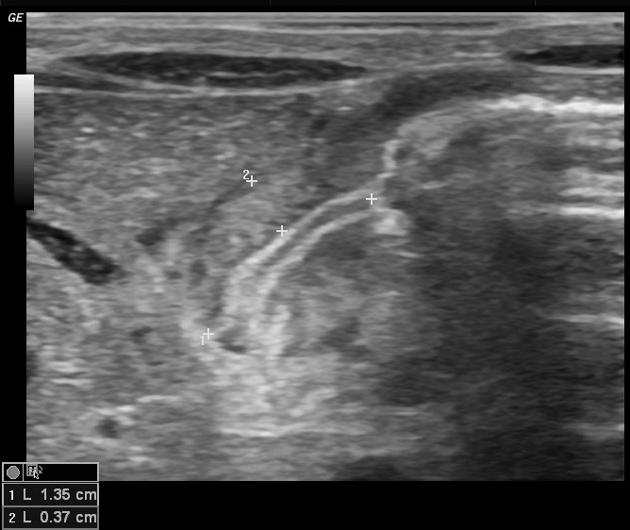

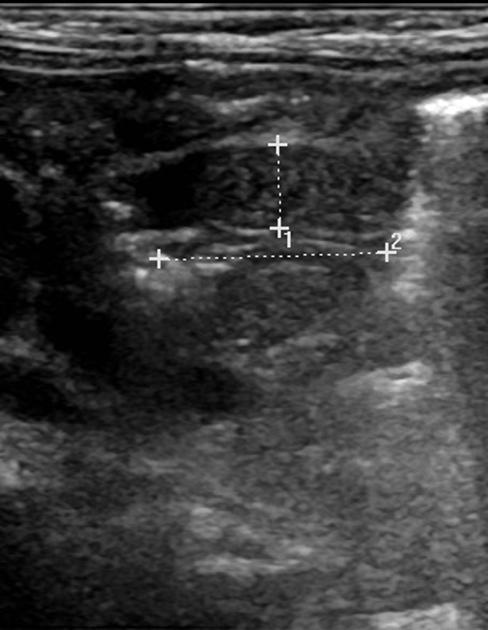

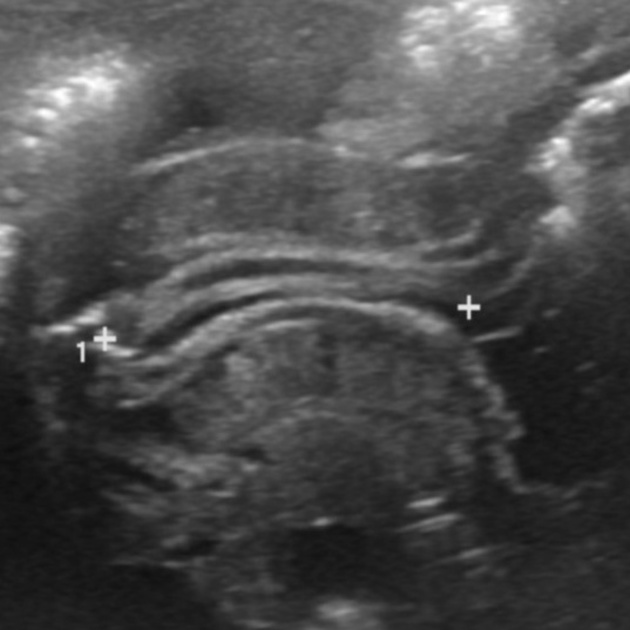

The hypertrophied muscle is hypoechoic, and the central mucosa is hyperechoic. Diagnostic measurements include (mnemonic "number pi" - 3.1415):

pyloric muscle thickness, i.e. diameter of a single muscular wall (hypoechoic component) on a transverse image: >3 mm (most accurate 3)

pyloric transverse diameter: >14 mm

length, i.e. longitudinal measurement: >15-17 mm

pyloric volume: >1.5 cm3

With the patient's right side down the pylorus should be watched and should not be seen to open.

Described sonographic signs include:

cervix sign 13

target sign 13

retrograde peristalsis 14

exaggerated peristaltic waves 14

Treatment and prognosis

Initial medical management is essential with rehydration and correction of electrolyte imbalances. This should be completed prior to surgical intervention.

Treatment is surgical with a pyloromyotomy in which the pyloric muscle is divided down to the submucosa. This can be performed both open and laparoscopically. The operation is curative and has very low morbidity 4,5. Recurrence is rare and usually due to an incomplete pyloromyotomy 11.

Differential diagnosis

There is usually little differential when imaging findings are appropriate. Of course, clinically it is important to consider other causes of vomiting in infancy.

A degree of pylorospasm is common in infancy and is responsible for some delay in gastric emptying. The pylorus, however, appears sonographically normal. In cases where the doubts persist, fluid gastric distention can be performed to "open" a tapered pylorus.

Gastro-esophageal reflux which represents the cause of vomiting in two-thirds of infants referred to radiology 8.

Other causes of proximal gastrointestinal obstruction can be considered 8:

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.