Nasopharyngeal carcinoma

Updates to Article Attributes

A nasopharyngealNasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is the most common primary malignancy of the nasopharynx. It is of squamous cell origin and some types of which are strongly associated with Epstein Barr virus (EBV).

Epidemiology

Nasopharyngeal carcinomas account for approximately 70% of all primary malignancies of the nasopharynx, and although it is rare in western populations, it is one of the most common malignancies encountered in Asia, especially China 1,3-5.

Risk factors are different depending on the histologic type of tumour present. Type I (keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma) can be thought of as a run-of-the-mill head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, which happens to be located in the nasopharynx. Its biological behaviour is similar and it shares the same risk factors, namely smoking and alcohol 2.

Types II and III on the other hand (non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma and undifferentiated carcinoma respectively) are strongly associated with Epstein Barr virus (EBV) and are seen particularly in Asia 1-4. Additional risk factors include consumption of salted fish and meat and rancid butter 2.

Clinical presentation

Clinical presentation, and often only when the tumour has grown significantly in size and has invaded adjacent structures.

Early, but often ignored symptoms, include nasal obstruction, epistaxis or conductive hearing loss due to Eustachian tube obstruction and the development of a middle ear effusion. Actual presentation is often delayed until more sinister signs are evident including nodal masses in the neck (most common), cranial nerve palsies, tinnitus, headache or even diplopia and proptosis 1-2.

Diagnosis is usually achieved with endoscopic guided biopsy 4. A minority of patients have submucosal disease, with normal appearing overlying mucosa. MRI is then essential in guiding biopsy 4.

Pathology

Nasopharyngeal carcinomas are divided into three types 1-2:

- type I - keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma

- type II - non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma (aka lymphoepithelioma)

- type III - undifferentiated carcinoma

All three types express cytokeratin, and types II and III have incorporation of the EBV into their genome, and circulating IgA antibodies to EBV in peripheral blood 1-4.

Staging

See nasopharyngeal carcinoma staging

Radiographic features

Imaging is crucial in delineating the extent of local tumour extension, as well as detecting nodal metastases which are present in the vast majority of patients at the time of diagnosis (75-90%) 1,3. Unfortunately imaging in isolation is not only unable to distinguish between the various types of nasopharyngeal carcinoma, but also unable to distinguish NPCs from other primary malignancies of the nasopharynx 1.

CT

CT is not only more readily available but is also the ideal modality to assess early bony involvement. Nasopharyngeal carcinomas appear as soft tissue masses most commonly centred at the lateral nasopharyngeal recess (fossa of Rosenmüller).

Small lesions, are confined to the nasopharynx by the pharyngobasilar fascia, and are indistinguishable from prominent adenoidal tissue.

Larger / more aggressive tumours may extend into any direction, eroding the base of skull and passing via the Eustachian tube, foramen lacerum, foramen ovale or directly through bone into the clivus, cavernous sinus and temporal bone. In such cases the bone has irregular margins where it has been destroyed, characteristic of aggressive processes.

Soft tissue extension can occur in any direction, with irregular infiltrating margins.

Following administration of contrast the tumour mass and nodal metastases usually demonstrate heterogeneous enhancement.

Careful assessment of cervical lymph nodes is essential due to the high rate of nodal involvement at the time of diagnosis. The retropharyngeal nodes are usually the first affected, however in up to 35% of cases these nodes are skipped, and level II nodes involved first 1,3.

Post radiotherapy fibrosis can mimic residual tumour on CT 3.

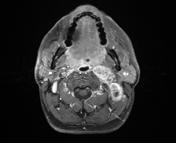

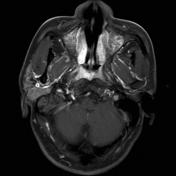

MRI

MRI is more sensitive to perineural spread and for demonstrating early the bone marrow changes of infiltration (see normal bone marrow signal of the clivus), although not all bone marrow changes represent tumour extension 3. Similarly dural thickening may be both evidence of tumour infiltration or reactive hyperplasia 3.

-

T1

-: typically isointense to muscle -

T2

-:- isointense to somewhat hyperintense to muscle

- fat saturation is helpful 5

- fluid in the middle ear is a helpful marker

-

T1 C+ (Gd)

-:- post contrast sequences should be fat saturated

- prominent heterogeneous enhancement is typical

- perineural extension should be sought

Post radiotherapy fibrosis can be distinguished from recurrent / residual tumour on MR if the fibrosis is mature. In such cases fibrotic scarring is of low signal intensity on T2 and does not demonstrate enhancement. Early fibrotic change cannot be distinguished from residual / recurrent tumour as both may be hyperintense on T2 and demonstrate enhanement 3.

Treatment and prognosis

The mainstay of treatment is external beam radiotherapy, supplemented in some cases with chemotherapy. Surgery has little role in the management of nasopharyngeal carcinoma other than for the purposes of diagnostic biopsy.

Prognosis is influenced both by stage and tumour type.

- type I - keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma - 42% 5 year survival 1

- type II - non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma - 65% 5 year survival

- type III - undifferentiated carcinoma - 14% 5 year survival

Complications

A potential complication of radiotherapy is radiation necrosis of the temporal lobes, as well as cranial nerve dysfunction and atrophy and fibrosis of the muscles of mastication and salivary glands 3.

Differential diagnosis

On imaging alone, nasopharyngeal carcinomas appear similar to other primary nasopharyngeal malignancies. Tumours of the skull base should also be included in the differential, especially when significant bony involvement is present.

The differential for a small mass confined to the mucosal space includes:

- prominent but normal adenoidal tissue

- often has a striped appearance on MRI on T1 and T2 weighted images 4

- nasopharyngeal lymphoma

- low grade / early other primary nasopharyngeal malignancies

The differential for a larger mass with involvement of base of skull includes all of the above, with the addition of the following:

- metastases

- chordoma

- chondrosarcoma

- meningioma

- even pituitary macroadenoma

-<p>A<strong> nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC)</strong> is the most common <a href="/articles/primary-malignancies-of-the-nasopharynx">primary malignancy of the nasopharynx</a>. It is of squamous cell origin and some types of which are strongly associated with <a href="/articles/ebv">Epstein Barr virus (EBV)</a>.</p><h4>Epidemiology</h4><p>Nasopharyngeal carcinomas account for approximately 70% of all primary malignancies of the nasopharynx, and although it is rare in western populations, it is one of the most common malignancies encountered in Asia, especially China <sup>1,3-5</sup>.</p><p>Risk factors are different depending on the histologic type of tumour present. Type I (keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma) can be thought of as a run-of-the-mill <a href="/articles/head-and-neck-squamous-cell-carcinoma">head and neck squamous cell carcinoma</a>, which happens to be located in the nasopharynx. Its biological behaviour is similar and it shares the same risk factors, namely smoking and alcohol <sup>2</sup>. </p><p>Types II and III on the other hand (non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma and undifferentiated carcinoma respectively) are strongly associated with Epstein Barr virus (EBV) and are seen particularly in Asia <sup>1-4</sup>. Additional risk factors include consumption of salted fish and meat and rancid butter <sup>2</sup>. </p><h4>Clinical presentation</h4><p>Clinical presentation, and often only when the tumour has grown significantly in size and has invaded adjacent structures.</p><p>Early, but often ignored symptoms, include nasal obstruction, epistaxis or conductive hearing loss due to <a href="/articles/eustachian-tube">Eustachian tube</a> obstruction and the development of a <a href="/articles/middle_ear_effusion">middle ear effusion</a>. Actual presentation is often delayed until more sinister signs are evident including nodal masses in the neck (most common), cranial nerve palsies, tinnitus, headache or even diplopia and proptosis <sup>1-2</sup>.</p><p>Diagnosis is usually achieved with endoscopic guided biopsy <sup>4</sup>. A minority of patients have submucosal disease, with normal appearing overlying mucosa. MRI is then essential in guiding biopsy <sup>4</sup>.</p><h4>Pathology</h4><p>Nasopharyngeal carcinomas are divided into three types <sup>1-2</sup>:</p><ol>- +<p><strong>Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC)</strong> is the most common <a href="/articles/primary-malignancies-of-the-nasopharynx">primary malignancy of the nasopharynx</a>. It is of squamous cell origin and some types of which are strongly associated with <a href="/articles/ebv">Epstein Barr virus (EBV)</a>.</p><h4>Epidemiology</h4><p>Nasopharyngeal carcinomas account for approximately 70% of all primary malignancies of the nasopharynx, and although it is rare in western populations, it is one of the most common malignancies encountered in Asia, especially China <sup>1,3-5</sup>.</p><p>Risk factors are different depending on the histologic type of tumour present. Type I (keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma) can be thought of as a run-of-the-mill <a href="/articles/head-and-neck-squamous-cell-carcinoma">head and neck squamous cell carcinoma</a>, which happens to be located in the nasopharynx. Its biological behaviour is similar and it shares the same risk factors, namely smoking and alcohol <sup>2</sup>. </p><p>Types II and III on the other hand (non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma and undifferentiated carcinoma respectively) are strongly associated with Epstein Barr virus (EBV) and are seen particularly in Asia <sup>1-4</sup>. Additional risk factors include consumption of salted fish and meat and rancid butter <sup>2</sup>. </p><h4>Clinical presentation</h4><p>Clinical presentation, and often only when the tumour has grown significantly in size and has invaded adjacent structures.</p><p>Early, but often ignored symptoms, include nasal obstruction, epistaxis or conductive hearing loss due to <a href="/articles/eustachian-tube">Eustachian tube</a> obstruction and the development of a <a href="/articles/middle-ear-effusion">middle ear effusion</a>. Actual presentation is often delayed until more sinister signs are evident including nodal masses in the neck (most common), cranial nerve palsies, tinnitus, headache or even diplopia and proptosis <sup>1-2</sup>.</p><p>Diagnosis is usually achieved with endoscopic guided biopsy <sup>4</sup>. A minority of patients have submucosal disease, with normal appearing overlying mucosa. MRI is then essential in guiding biopsy <sup>4</sup>.</p><h4>Pathology</h4><p>Nasopharyngeal carcinomas are divided into three types <sup>1-2</sup>:</p><ol>

-</ol><p>All three types express cytokeratin, and types II and III have incorporation of the EBV into their genome, and circulating IgA antibodies to EBV in peripheral blood <sup>1-4</sup>.</p><h5>Staging</h5><p>See <a href="/articles/nasopharyngeal-carcinoma-staging">nasopharyngeal carcinoma staging</a></p><h4>Radiographic features</h4><p>Imaging is crucial in delineating the extent of local tumour extension, as well as detecting nodal metastases which are present in the vast majority of patients at the time of diagnosis (75-90%) <sup>1,3</sup>. Unfortunately imaging in isolation is not only unable to distinguish between the various types of nasopharyngeal carcinoma, but also unable to distinguish NPCs from other <a href="/articles/primary-malignancies-of-the-nasopharynx">primary malignancies of the nasopharynx</a> <sup>1</sup>.</p><h5>CT</h5><p>CT is not only more readily available but is also the ideal modality to assess early bony involvement. Nasopharyngeal carcinomas appear as soft tissue masses most commonly centred at the <a href="/articles/fossa_of_rosenm%C3%BCller">lateral nasopharyngeal recess</a> (fossa of Rosenmüller).</p><p>Small lesions, are confined to the nasopharynx by the <a href="/articles/pharyngobasilar-fascia">pharyngobasilar fascia</a>, and are indistinguishable from prominent adenoidal tissue.</p><p>Larger / more aggressive tumours may extend into any direction, eroding the <a title="Base of skull" href="/articles/base-of-skull">base of skull</a> and passing via the <a href="/articles/eustachian-tube">Eustachian tube</a>, <a href="/articles/foramen-lacerum">foramen lacerum</a>, <a href="/articles/foramen-ovale">foramen ovale</a> or directly through bone into the <a href="/articles/clivus">clivus</a>, <a href="/articles/cavernous-sinus">cavernous sinus</a> and <a href="/articles/temporal-bone-1">temporal bone</a>. In such cases the bone has irregular margins where it has been destroyed, characteristic of aggressive processes.</p><p>Soft tissue extension can occur in any direction, with irregular infiltrating margins.</p><p>Following administration of contrast the tumour mass and nodal metastases usually demonstrate heterogeneous enhancement. </p><p>Careful assessment of cervical lymph nodes is essential due to the high rate of nodal involvement at the time of diagnosis. The retropharyngeal nodes are usually the first affected, however in up to 35% of cases these nodes are skipped, and <a href="/articles/lymph-node-levels-of-the-neck">level II nodes</a> involved first <sup>1,3</sup>. </p><p>Post radiotherapy fibrosis can mimic residual tumour on CT <sup>3</sup>.</p><h5>MRI</h5><p>MRI is more sensitive to perineural spread and for demonstrating early the bone marrow changes of infiltration (see <a href="/articles/normal-bone-marrow-signal-of-the-clivus">normal bone marrow signal of the clivus</a>), although not all bone marrow changes represent tumour extension <sup>3</sup>. Similarly dural thickening may be both evidence of tumour infiltration or reactive hyperplasia <sup>3</sup>.</p><ul>- +</ol><p>All three types express cytokeratin, and types II and III have incorporation of the EBV into their genome, and circulating IgA antibodies to EBV in peripheral blood <sup>1-4</sup>.</p><h5>Staging</h5><p>See <a href="/articles/nasopharyngeal-carcinoma-staging">nasopharyngeal carcinoma staging</a></p><h4>Radiographic features</h4><p>Imaging is crucial in delineating the extent of local tumour extension, as well as detecting nodal metastases which are present in the vast majority of patients at the time of diagnosis (75-90%) <sup>1,3</sup>. Unfortunately imaging in isolation is not only unable to distinguish between the various types of nasopharyngeal carcinoma, but also unable to distinguish NPCs from other <a href="/articles/primary-malignancies-of-the-nasopharynx">primary malignancies of the nasopharynx</a> <sup>1</sup>.</p><h5>CT</h5><p>CT is not only more readily available but is also the ideal modality to assess early bony involvement. Nasopharyngeal carcinomas appear as soft tissue masses most commonly centred at the <a href="/articles/fossa-of-rosenmuller-2">lateral nasopharyngeal recess</a> (fossa of Rosenmüller).</p><p>Small lesions, are confined to the nasopharynx by the <a href="/articles/pharyngobasilar-fascia">pharyngobasilar fascia</a>, and are indistinguishable from prominent adenoidal tissue.</p><p>Larger / more aggressive tumours may extend into any direction, eroding the <a href="/articles/base-of-skull">base of skull</a> and passing via the <a href="/articles/eustachian-tube">Eustachian tube</a>, <a href="/articles/foramen-lacerum">foramen lacerum</a>, <a href="/articles/foramen-ovale-head">foramen ovale</a> or directly through bone into the <a href="/articles/clivus">clivus</a>, <a href="/articles/cavernous-sinus">cavernous sinus</a> and <a href="/articles/temporal-bone-1">temporal bone</a>. In such cases the bone has irregular margins where it has been destroyed, characteristic of aggressive processes.</p><p>Soft tissue extension can occur in any direction, with irregular infiltrating margins.</p><p>Following administration of contrast the tumour mass and nodal metastases usually demonstrate heterogeneous enhancement. </p><p>Careful assessment of cervical lymph nodes is essential due to the high rate of nodal involvement at the time of diagnosis. The retropharyngeal nodes are usually the first affected, however in up to 35% of cases these nodes are skipped, and <a href="/articles/lymph-node-levels-of-the-neck">level II nodes</a> involved first <sup>1,3</sup>. </p><p>Post radiotherapy fibrosis can mimic residual tumour on CT <sup>3</sup>.</p><h5>MRI</h5><p>MRI is more sensitive to perineural spread and for demonstrating early the bone marrow changes of infiltration (see <a href="/articles/normal-bone-marrow-signal-of-the-clivus">normal bone marrow signal of the clivus</a>), although not all bone marrow changes represent tumour extension <sup>3</sup>. Similarly dural thickening may be both evidence of tumour infiltration or reactive hyperplasia <sup>3</sup>.</p><ul>

-<strong>T1</strong> - typically isointense to muscle</li>- +<strong>T1</strong>: typically isointense to muscle</li>

-<strong>T2</strong> -<ul>- +<strong>T2</strong>:<ul>

-<strong>T1 C+ (Gd)</strong> -<ul>- +<strong>T1 C+ (Gd)</strong>:<ul>

Image 3 MRI (T2) ( update )

Image 4 MRI (T1) ( update )

Image 5 MRI (T2) ( update )

Image 6 MRI (T1 C+) ( update )

Image 7 MRI (T1 C+) ( update )

Image 8 MRI (T2) ( update )

Image 9 MRI (T1) ( update )

Image 10 MRI (T1 C+ fat sat) ( update )

Image 14 MRI (T1 C+) ( update )

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.