Crohn disease, also known as regional enteritis, is an idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease characterized by widespread discontinuous gastrointestinal tract inflammation. The terminal ileum and proximal colon are most often affected. Extraintestinal disease is common.

On this page:

Epidemiology

The diagnosis is typically made between the ages of 15 and 25 years with no gender predilection 5. There is a familial component and incidence varies geographically.

Associations

celiac disease: 3-4x increased risk 46

Clinical presentation

Patients typically present with chronic diarrhea and recurrent abdominal pain, although occasionally the presentation is with a complication or an extraintestinal manifestation. Anemia may be present and C-reactive protein may be elevated 29.

Fecal calprotectin has been increasingly used to:

distinguish inflammatory bowel disease from irritable bowel syndrome

assess disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease, including acute exacerbations and response to treatment 26

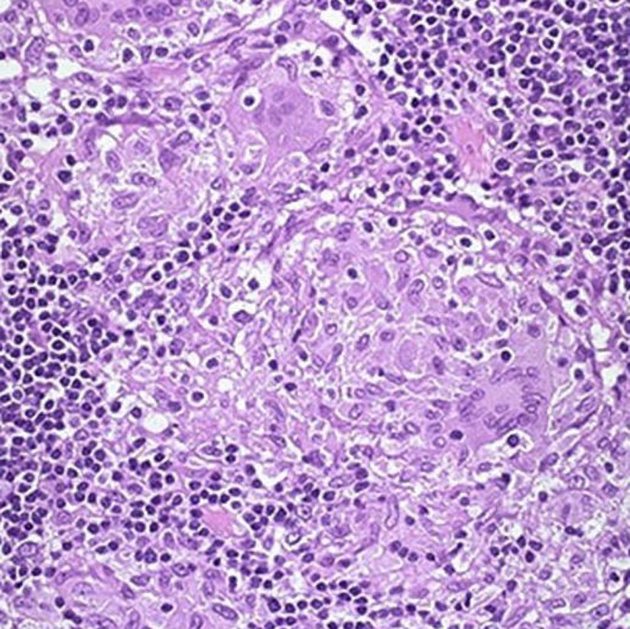

Pathology

Crohn disease remains idiopathic, although infective agents have been gaining in popularity as a possible cause, including the measles virus and atypical mycobacterium. As there are definite genetic factors at play, multiple factors are likely to contribute 1. Incidence is higher in people with first degree relatives having IBD, reaching up to 10%; in children whose parents both have Crohn disease, incidence reaches 30%. Also, disease concordance among monozygous and heterozygous twins has been shown, with a 30-50% chance of developing the disease in a twin of an affected person.

Initially, the disease is limited to the mucosa with neutrophilic cryptitis and lymphoid hyperplasia, lymphedema and shallow aphthoid ulceration. As the disease progresses, the entire bowel wall becomes involved, with linear longitudinal and circumferential ulcers extending deep into the bowel wall, predisposing to fistulae. Inflammation also extends into the mesentery and over time leads to chronic fibrotic change, and stricture formation 5.

Inflammation can occur anywhere along the digestive tract, including the mouth and esophagus. Crohn disease of the esophagus should only be considered if Crohn disease of the bowel is already evident 44. The following findings are evidences of Crohn disease involving the mouth and esophagus:

mucogingivitis

mucosal tags

deep ulcerations

cobblestoning

lip swelling

pyostomatitis vegetans

esophageal ulcers and strictures

Extraintestinal manifestations include 3,15-17:

-

skin

aphthous stomatitis 35

enterocutaneous fistulas 42

-

joints

arthritis

sacroiliitis (one of the most frequent extraintestinal manifestations)

-

eyes

episcleritis

iritis

uveitis (acute anterior uveitis)

-

liver and biliary system

pericholangitis

primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) (more common in ulcerative colitis)

gallstones: seen in 30-50% 8

portal vein thrombosis (rare, yet higher than the general population) 34

fatty infiltration of the liver (steroid therapy, hyperalimentation) 31

-

renal tract

-

renal calculi containing oxalate

the poor fat absorption results in binding of calcium by fats, which in turn reduces the amount of calcium that can bind to oxalate, therefore increasing the amount of unbound oxalate available for resorption; this resorption occurs in the colon, and therefore patients with an ileostomy do not have the same increased risk

ileoureteral or ileovesical fistula 31,32

-

Classification

Recognized classifications include:

Radiographic features

The characteristic of Crohn disease is the presence of skip lesions and discrete ulcers. The frequency with which various parts of the gastrointestinal tract are affected varies widely 5:

small bowel: 70-80% 5,6; the terminal ileum is usually affected first 33

small and large bowel: 50%

large bowel only: 15-20%

The choice of investigation modality depends on local expertise and availability. CT and MR enterography are similar in sensitivity for active inflammation (89% vs 83% respectively) and both are better than small bowel follow-through (67-72%) 6. The lack of ionizing radiation from MRI would make it a better option, however, the availability of MRI is limited in many countries.

Ultrasound, which has been largely applied by gastroenterologists, is also an option for diagnosing active disease, following-up treatment response, and assessing complications 20. It has a reported sensitivity of 75-94% and specificity of 67-100% 20.

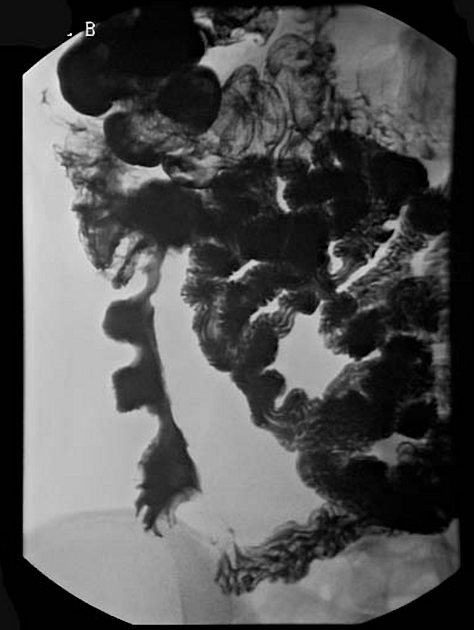

Fluoroscopy

Features on barium small bowel follow-through include:

-

mucosal ulcers

aphthous ulcers initially

deep ulcers (>3 mm depth)

longitudinal fissures

transverse stripes

when severe leads to cobblestone appearance

may lead to sinus tracts and fistulae

widely separated loops of bowel due to fibrofatty proliferation (creeping fat) 2

thickened folds due to edema

pseudodiverticula/pseudosacculation formation: due to contraction at the site of ulcer with ballooning of the opposite (usually antimesenteric) side

string sign: tubular narrowing due to spasm or stricture depending on the chronicity

partial obstruction

on control films presence of gallstones, renal oxalate stones, and sacroiliac joint or lumbosacral spine changes should be sought

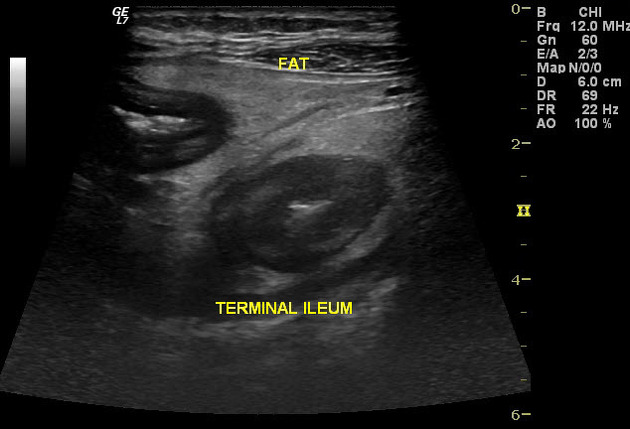

Ultrasound

Ultrasound has a limited role, but due to it being cheap, available, and not involving ionizing radiation, it has been evaluated as an initial screening tool for active disease and also for follow-up and to assess complications 4,20. Features that may be discovered during transabdominal sonography include 39:

-

small bowel wall thickening (>3-4 mm)

needs to be interpreted in the context of pretest probability

affected loops are often non-compressible and are difficult to displace with transducer pressure

affected segments lose peristaltic activity 38

-

loss of mural stratification

the gut signature is characteristic of small bowel

chronic disease activity may result in collagen deposition within the wall, which imitates the appearance of the normal submucosa

-

bowel wall hyperemia

-

hyperechoic, circumferential layer external to the bowel wall

represents fibrofatty proliferation, thought to represent active inflammation

interruption by hypoechoic mesenteric streaks imply a greater degree of inflammation

-

mesenteric lymphadenopathy

three or more mesenteric lymph nodes enlarged, measured over 4 mm (width) or 8 mm (length)

-

thought to be secondary to transmural inflammation

fibrofatty proliferation and creeping fat visible as increased fat echogenicity surrounding the bowel loops

On pulsed-wave Doppler evaluation, increased superior mesenteric artery (SMA) flow volume and decreased SMA resistive index (SMA RI) also correlate with disease activity. Successful treatment may result in the normalization on Color flow Doppler 12.

Complications may also be assessed with sonography, with the following features commonly detected in the following 37:

-

abscess formation

irregular, echo-poor collection with a variable amount of internal echogenic material and posterior acoustic enhancement

absence of internal flow (by color flow Doppler)

may demonstrate peripheral vascularity with power Doppler

-

fistula creation

linear, anechoic tract extending from an affected bowel loop to another structure, often with scattered hyperechoic puncta with inhomogeneous posterior acoustic shadowing (air)

diameter of the fistulous tract should be <2 cm 41

-

luminal stenosis

segmental wall thickening, loss of peristalsis, luminal narrowing or obliteration, preceding segment dilated (>2.5 cm)

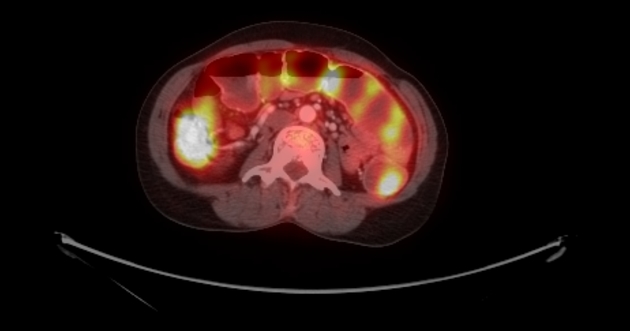

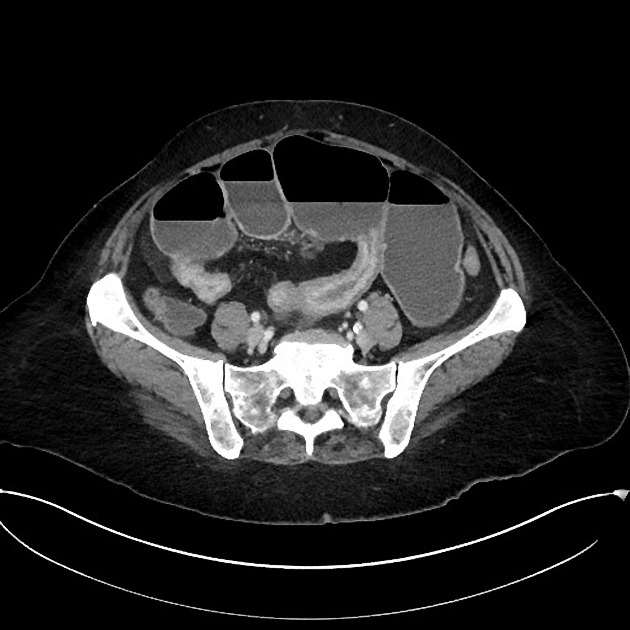

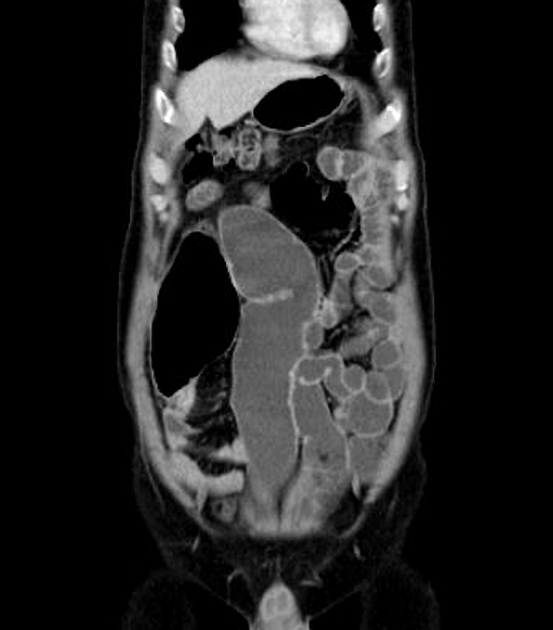

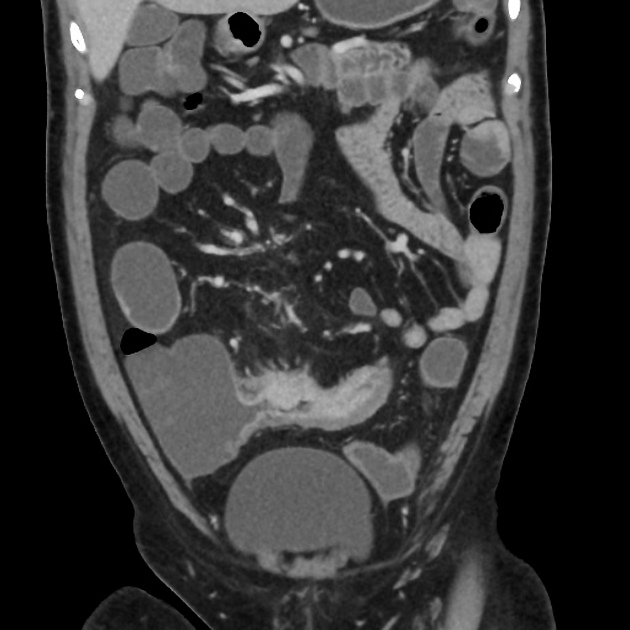

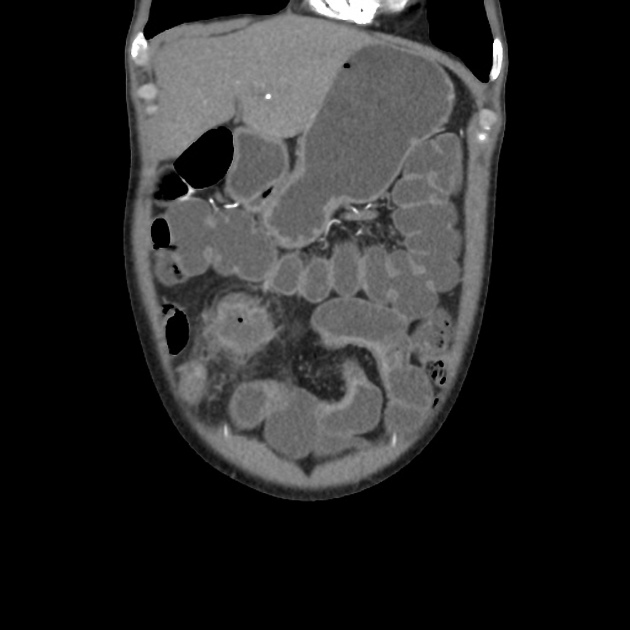

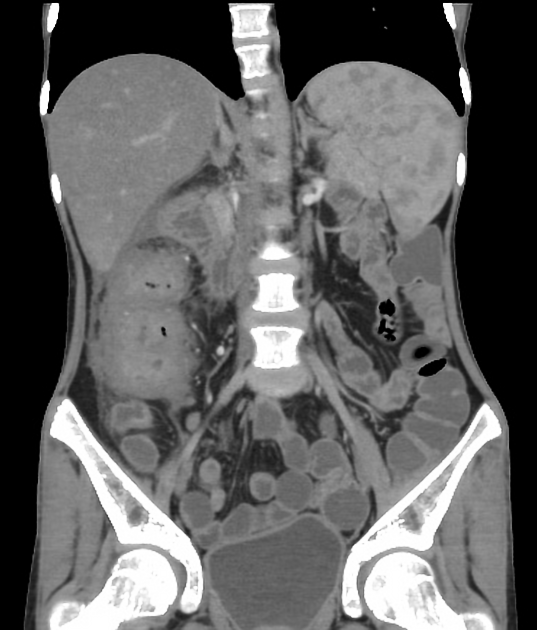

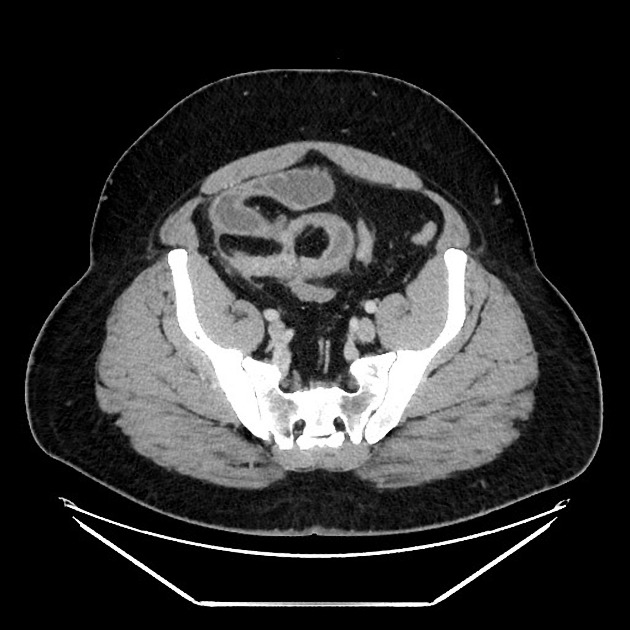

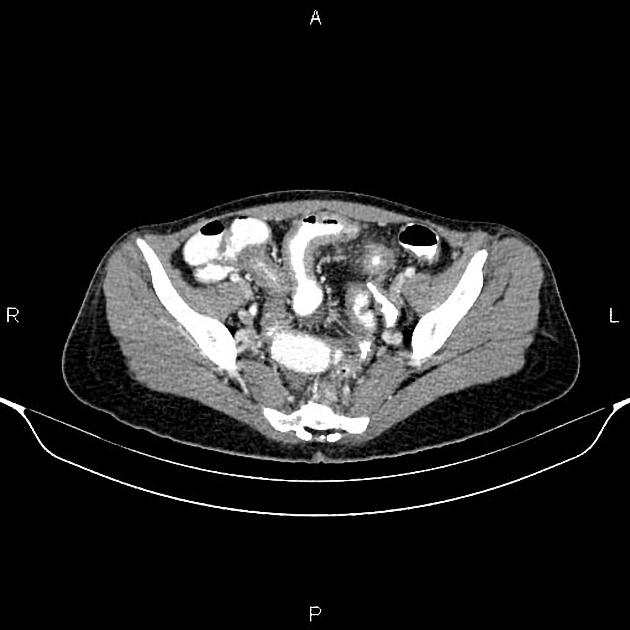

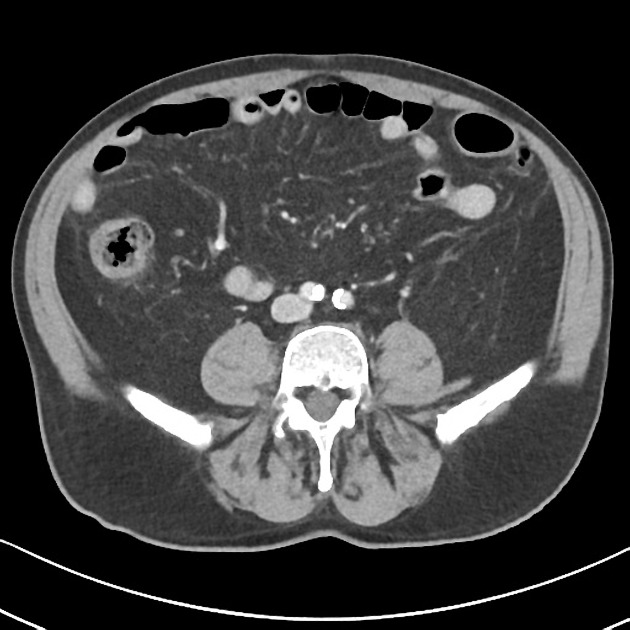

CT

CT is commonly the first imaging assessment of those patients in the setting of an acute abdomen, or it can be also applied to the reassessment of complications in patients with known Crohn disease. Common features include:

mural hyperenhancement

fat halo sign: submucosal fat deposition

bowel wall thickening (1-2 cm), which is most frequently seen in the terminal ileum (present in up to 83% of patients) 8

comb sign: engorgement of the vasa recta

perienteric fat stranding

affected bowel loops separated by focal/regionally increased fat (fibrofatty proliferation; creeping fat)

strictures and fistulae, with upstream dilatation

-

mesenteric/intra-abdominal abscess or phlegmon formation 8

abscesses are eventually seen in 15-20% of patients 8

CT is also able to give valuable information on:

perianal disease

hepatobiliary disease

CT enterography

CT enterography is superior to standard CT studies when assessing for small bowel Crohn disease and is equivalent to MR enterography, the downside compared to the latter being ionizing radiation. CT enteroclysis may be attempted in selected patients. For the imaging findings and descriptors in CT enterography, see the discussion below under MR enterography.

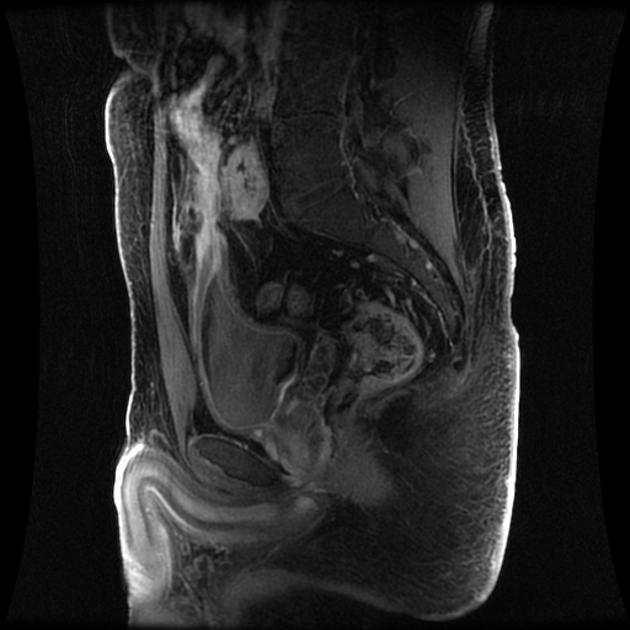

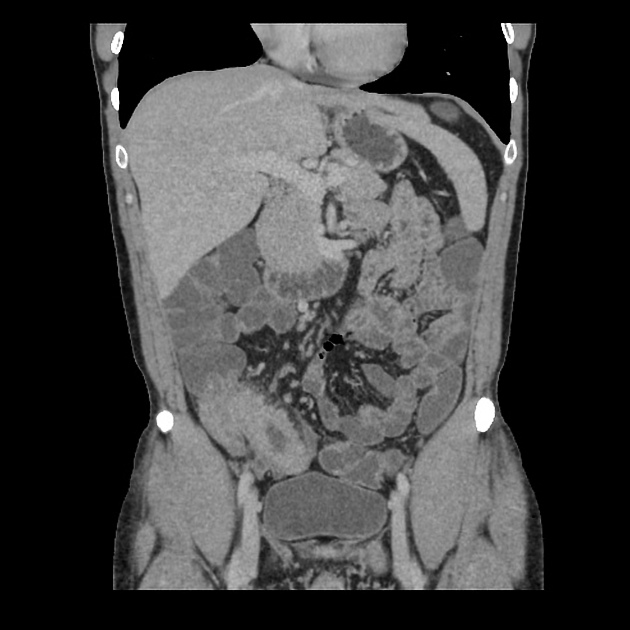

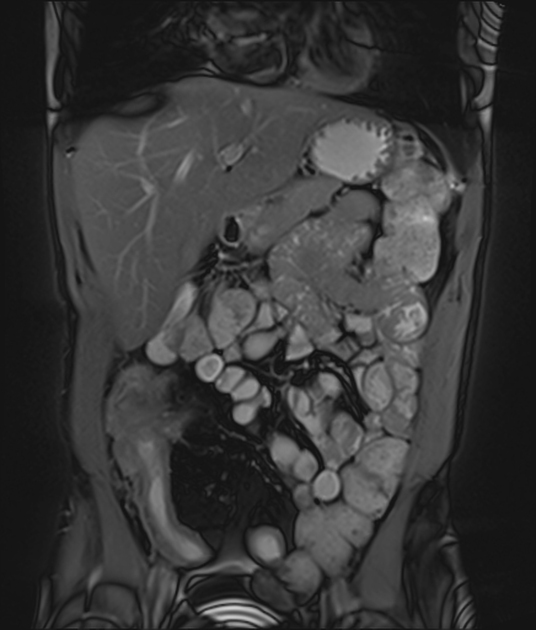

MRI

MR enterography has become an increasingly important part of the management of patients with Crohn disease. MR enteroclysis may be attempted in selected patients.

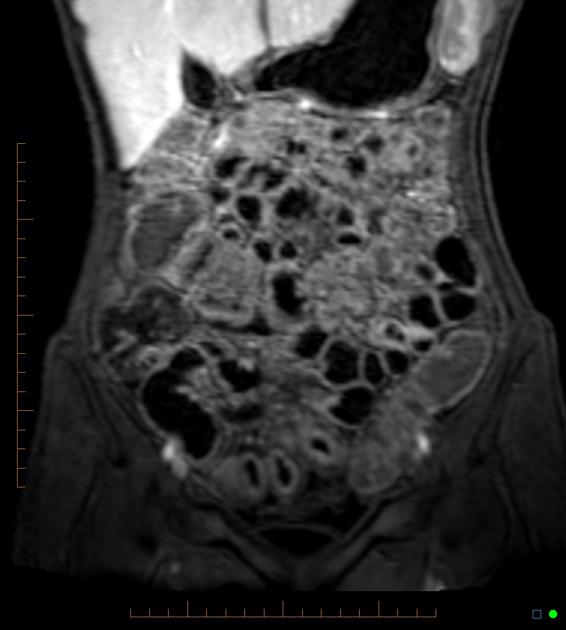

MR enterography (MRE)

Features of small bowel Crohn disease to be assessed on dedicated MRI study include:

-

segmental mural hyperenhancement

-

asymmetric

specific sign for Crohn disease

tends to more frequently involve the mesenteric border of a small bowel loop

-

stratified: layers of enhancement within the bowel wall

-

bilaminar: hyperenhancement of the inner layer

please note that the term “mucosal hyperenhancement” is discouraged given the mucosa itself is absent in the Crohn inflamed bowel segments 43

-

trilaminar: hyperenhancement of both the inner and outer layers of the small bowel wall

more frequently seen on MR enterography (cf. CT enterography)

it can be explained by a combination of intramural submucosal edema, granulation tissue, intramural fat deposition (fat halo sign on CT), or fibrosis

-

-

homogeneous or transmural hyperenhancement: involving the entire small bowel wall

less specific and, depending on distribution, other differentials should apply

-

DWI: restricted diffusion is seen within the small bowel wall segments of active inflammation 43

-

wall thickening 22,43: must be assessed in a loop adequately distended by fluid

mild 3-5 mm

moderate >5-9 mm

severe >9 mm

please note that focal thickening over 15 mm is atypical for Crohn disease, and consideration for malignancy should be sought 43

-

intramural edema

better assessed on MRI T2 fat-saturated or low b-value DWI sequences

increased T2 signal in the thickened bowel wall is particularly helpful in evaluating for acute inflammation 25

-

stricture: focal narrowing of the lumen with immediate upstream bowel dilatation ≥3 cm. Bear in mind that sometimes the upstream loop is not dilated to size criterion due to decompression by a fistula/penetrating disease or limited bowel content inflow in the setting of two or more consecutive stricture segments 43

highly suspected stricture should be reported in persistent focal luminal narrowing across multiple MRI sequences

although they can be divided into fibrotic or inflamed strictures, the majority will have a component of active inflammation

location and length of the stricture should be reported

strong association of strictures and penetrating disease, so one should prompt the evaluation for the other

stricture vs obstruction: upstream dilatation >4 cm is advised to be reported as small bowel obstruction 43

ulcerations: focal defect at the intraluminal aspect of the small bowel wall, confined within the serosa (cf. sinus tract)

decreased peristalsis: coronal cine MRI sequences (bSSFP) can also be useful in diagnosis as inflamed loops of bowel frequently demonstrate decreased peristalsis

pseudodiverticula/pseudosacculation formation: broadband outpouching along the antimesenteric border

Mesenteric signs of inflammation include:

engorged vasa recta: enlarged mesenteric blood vessels related to an inflamed bowel loop (comb sign)

-

fibrofatty proliferation (creeping fat):

hypertrophy of the mesenteric fat, which separates bowel loops

-

mesenteric venous thrombosis

usually adjacent to an inflamed loop

acute: distended vein

chronic: narrowed or interrupted vein

lymphadenopathy

Features of penetrating disease include:

sinus tract: blind-ended tract extending beyond the bowel serosa

-

fistula tract: tract that communicates the bowel lumen to another epithelialized surface

usually seen proximal to a small bowel stricture

active inflammation is almost always present

complex fistula: more than one tract associated with angulation or tethering of affected loops

inflammatory mass: mesenteric stranding (on CT) or increased T2 signal denoting inflammation but without fluid collections

abscess: a fluid collection with rim-enhancement

Extraintestinal involvement can be at least partially assessed on MR enterography, particularly, hepatobiliary disease (e.g. gallstones) and sacroiliitis.

In order to quantify disease severity and response to therapy several indices have been designed such as the Magnetic Resonance Index of Activity (MaRIA) and its later, simplified version (MARIAs). For non-contrast enterography the Clermont score can be used.

MRI pelvis

Crohn perianal disease is mostly characterized on imaging by perianal fistulas and is better evaluated using a dedicated MRI protocol for the anal canal. The original and modified Van Assche indices can be used for the semiquantitative assessment of disease severity and to evaluate response to therapy.

Treatment and prognosis

Management is complex as the condition is chronic with a relapsing-remitting course. Medical management broadly encompasses induction and maintenance therapy, with options including 7,47:

corticosteroids (e.g. prednisolone)

immunomodulation (e.g. thiopurines)

non-biological immunosuppression (e.g. methotrexate)

-

biological immunosuppression

tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitor (e.g. infliximab)

integrin inhibitor (e.g. vedolizumab)

interleukin 12/23 inhibitor (e.g. ustekinumab)

Surgical management is reserved for complications including:

strictures

adhesions and bowel obstructions

fistulae

-

perianal disease

History and etymology

It is named after Burrill Bernard Crohn (1884-1983), an American gastroenterologist, who described the condition as "regional ileitis" in his seminal 1932 paper 11,24. However, the first definite description (but see below) was nearly twenty years prior, by Sir Thomas Kennedy Dalziel (1861-1924), a Scottish surgeon, in 1913 21,23.

Antoni Leśniowski (1867-1940), a Polish surgeon, described a small bowel condition in 1904 in a small series of four patients, with similarities to Crohn disease, although it remains controversial if it was actually Crohn disease 27,28. At least one of the patients probably actually had ileal tuberculosis. Nevertheless, Polish physicians and journals usually call the condition Leśniowski-Crohn disease.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis depends on the presenting symptom. When terminal ileitis is the main presentation, then differentials (adjusted for patient's age) include 1:

When colonic involvement is the predominant feature then other considerations include:

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.