Extradural hematoma (EDH), also known as an epidural hematoma, is a collection of blood that forms between the inner surface of the skull and outer layer of the dura, which is called the endosteal layer. They are usually associated with a history of head trauma and frequently associated skull fracture. The source of bleeding is usually arterial, most commonly from a torn middle meningeal artery.

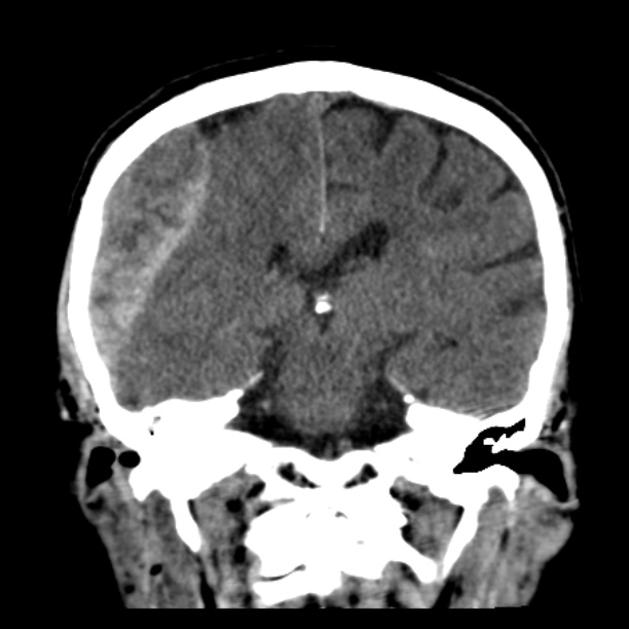

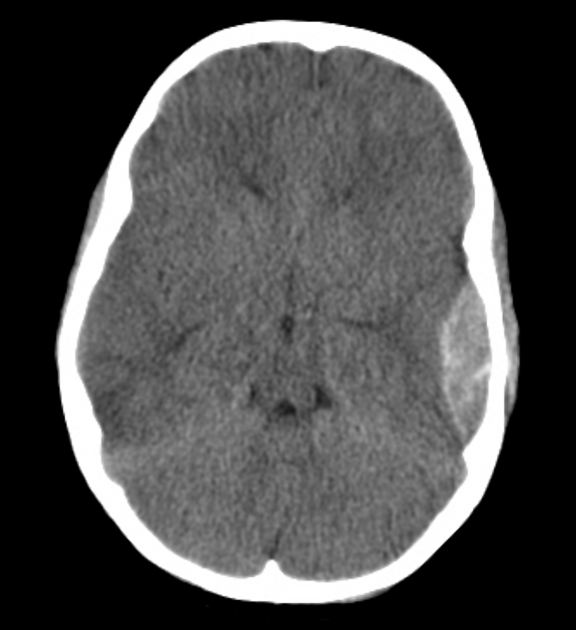

Extradural hematomas are typically biconvex in shape and can cause a mass effect with herniation. They are usually limited by cranial sutures, but not by venous sinuses. Both CT and MRI are suitable to evaluate extradural hematomas. When the blood clot is evacuated promptly (or sufficiently small to be treated conservatively), the prognosis of extradural hematomas is generally good.

Intracranial venous extradural hemorrhages and spinal epidural hemorrhages are discussed separately.

On this page:

Epidemiology

Typically extradural hematomas are seen in young patients who have sustained head trauma, usually with an associated skull fracture.

Clinical presentation

Unlike subdural hemorrhages, in which a history of head trauma is often difficult to clearly identify, extradural hemorrhages usually are precipitated by clearly defined head trauma.

A typical presentation is of a young patient who has sustained a head injury (either during sport or a result of a motor vehicle accident) who may or may not lose consciousness transiently. Following the injury, they regain a normal level of consciousness (lucid interval), but usually have an ongoing and often severe headache. Over the next few hours, they gradually lose consciousness.

Due to the long cisternal course of the sixth cranial nerve (abducens nerve, CN VI), it is often involved as downward herniation begins, usually on the side of the hemorrhage and can, in an emergency, guide exploratory burr holes.

See the article: extradural hemorrhage vs subdural hemorrhage.

Pathology

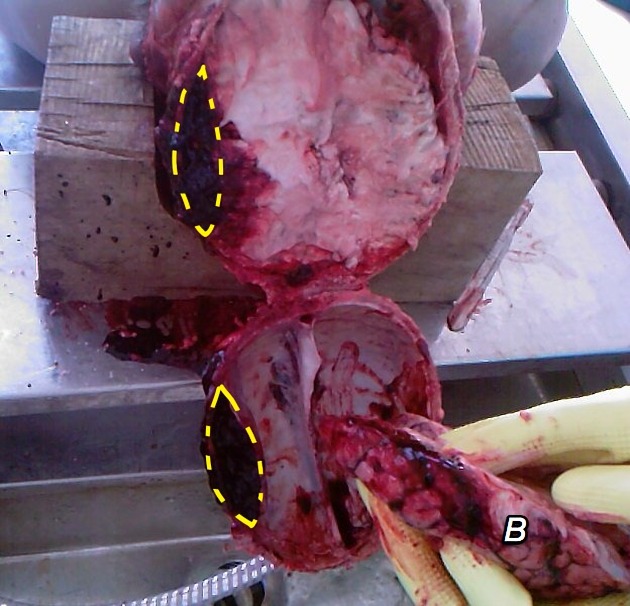

The source of bleeding is typically from a torn meningeal artery, usually the middle meningeal artery (75% 7). An associated skull fracture is present in ~75% of cases 3. Pain (often severe headache) is caused by the stripping of dura from the bone by the expanding hemorrhage. The posterior fossa is a rare location for traumatic injury, in general, including extradural hematomas 3,4.

Occasionally, an extradural hematoma can form due to venous blood, typically a torn sinus with an associated fracture: see venous extradural hemorrhage.

Young patients being affected is not only a result of the prevalent demographics of patients with a head injury but also relates to the changes that occur in the dura in older patients, as the dura is much more adherent to the inner surface of the skull.

It is important to realize that in the setting of sutural diastasis, extradural hematomas can cross sutures, as the continuation of the parietal (periosteal) component of the dura through the suture - which usually limits spread - is likely also to be disrupted.

Location

Extradural hematomas are generally unilateral in more than 95% of cases, however, bilateral or multiple extradural hematomas are reported.

-

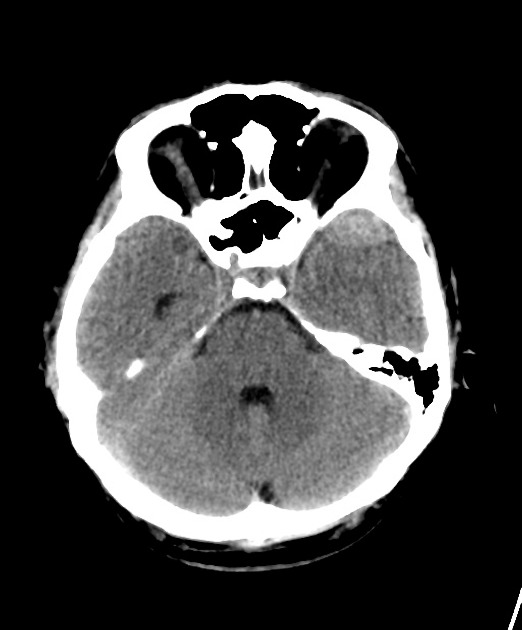

>95% are supratentorial

temporoparietal: 60%

frontal: 20%

parieto-occipital: 20%

<5% are located infratentorially in posterior fossa 4

Special locations to consider, particularly those related to venous extradural bleeding, include:

vertex extradural hematoma (which displaces the superior sagittal sinus) 6

-

anterior middle cranial fossa (anterior temporal) 7

likely venous bleeding (from the sphenoparietal sinus)

do not cause midline shift or herniation

rarely enlarge

can often be managed conservatively

Radiographic features

The morphology of extradural hematomas is best understood by reviewing their relationship to the bone and dura. An extradural hematoma is actually a subperiosteal hematoma located on the inside of the skull, between the inner table of the skull and parietal layer of the dura mater (which is the periosteum). As a result, extradural hematomas are usually limited in their extent by the cranial sutures, as the periosteum crosses through the suture continuous with the outer periosteal layer. This is therefore helpful in distinguishing extradural hematomas from subdural hematomas, which are not limited by sutures.

Extradural hemorrhages can, however, cross and elevate venous sinuses as long as there is no suture there; after all a venous sinus is located between the parietal and visceral layer of the dura.

Unfortunately, these rules are not foolproof and not infrequently extradural hematomas do cross sutures. One series found up to 11% of extradural hematomas in children cross sutures 5. This occurs in many scenarios:

skull fracture across the suture 5

vertex extradural hematomas, usually due to venous extradural hemorrhage, often cross the midline elevating the superior sagittal sinus 6

CT

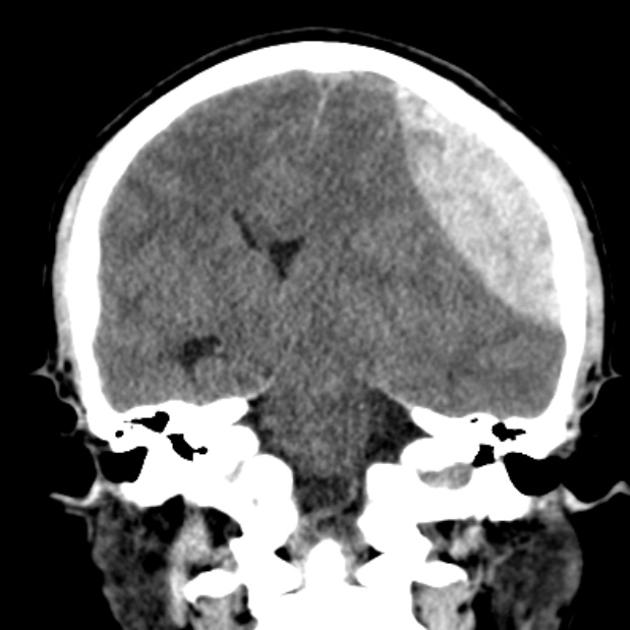

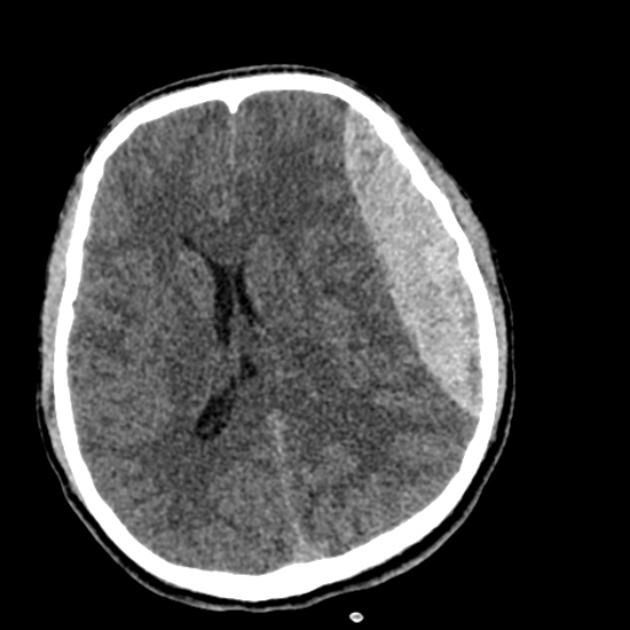

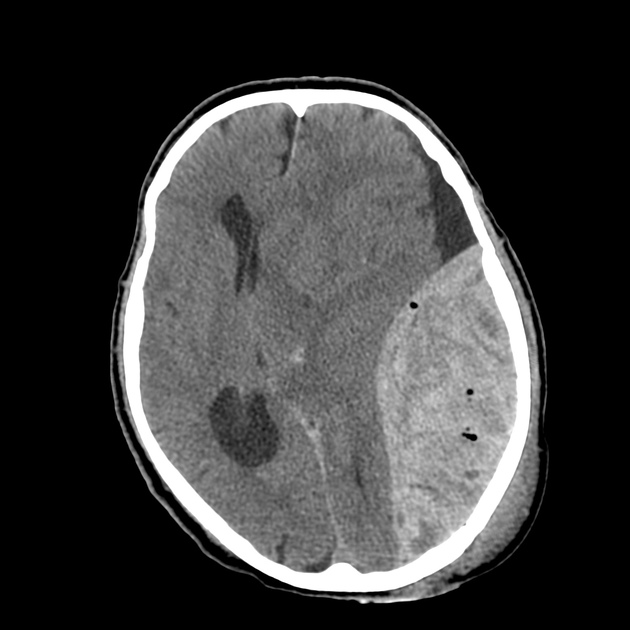

In almost all cases, extradural hematomas are seen on CT scans of the brain. They are typically bi-convex (or lentiform) in shape, and most frequently beneath the squamous part of the temporal bone. EDHs are hyperdense, somewhat heterogeneous, and sharply demarcated. Depending on their size, secondary features of mass effect (e.g. midline shift, subfalcine herniation, uncal herniation) may be present.

When acute bleeding is occurring at the time of CT scanning the non-clotted fresh blood is typically less hyperdense, and a swirl sign may be evident 1.

Postcontrast extravasation may be seen rarely in case of acute extradural hematoma and peripheral enhancement due to granulation and neovascularization can be seen in chronic extradural hematomas.

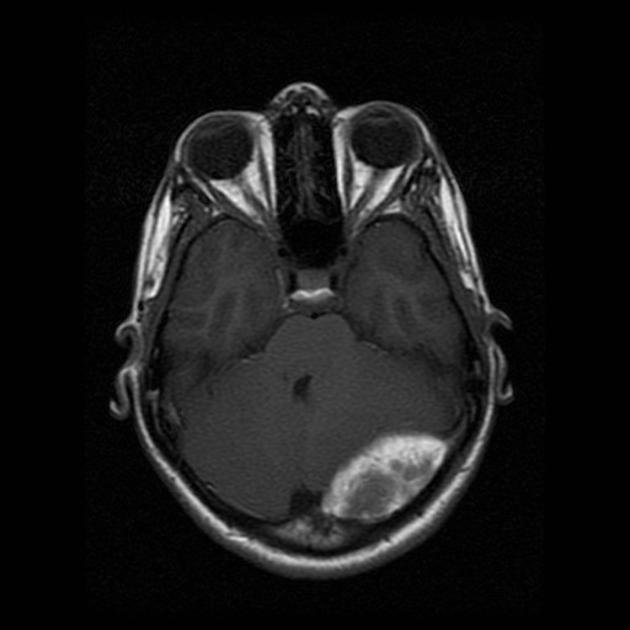

MRI

MRI can clearly demonstrate the displaced dura that appears as a hypointense line on T1 and T2 sequences which is helpful in distinguishing it from a subdural hematoma.

Acute extradural hematoma appears isointense on T1 and shows variable intensities from hypo- to hyperintense on a T2 sequence. Early subacute extradural hematoma appears hypointense on T2 while late subacute and chronic extradural hematomas are hyperintense on both T1 and T2 sequences.

Intravenous contrast may demonstrate displaced or occluded venous sinus in case of the venous origin of extradural hematomas.

Angiography

It can be used to evaluate nontraumatic cause (i.e. AVM) of extradural hematomas. Rarely angiography can demonstrate middle meningeal artery laceration and contrast extravasation from the middle meningeal artery into paired middle meningeal veins known as "tram track sign".

Treatment and prognosis

Prognosis, even with a relatively large hematoma, is in general quite good, as long as the clot is evacuated promptly. A smaller hematoma without mass effect or swirl sign can be treated conservatively 2, sometimes resulting in calcification of the dura.

Occasionally late complications are encountered, usually relating to the injured meningeal vessel. They include:

Differential diagnosis

With large hematomas, there is rarely significant confusion as to the correct diagnosis. In smaller lesions, especially when there is associated parenchymal injury (e.g. cerebral contusions, traumatic subarachnoid blood, concurrent subdural hematoma) the diagnosis can be more challenging.

Differential considerations include:

-

can cross sutures

usually sickle-shaped

limited by dural reflections

usually in older patients or in young patients with significant other closed head injuries

-

maybe hyperdense

enhances with contrast

usually remote from the fracture (e.g. parafalcine)

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.