Glioblastomas (GBM) are the most common adult primary brain tumor and are aggressive, relatively resistant to therapy, and have a corresponding poor prognosis.

They typically appear as heterogeneous masses centered in the white matter with irregular peripheral enhancement, central necrosis, and surrounding vasogenic edema, although molecular glioblastomas may appear indistinguishable from lower-grade astrocytoma, IDH-mutant.

Treatment primarily consists of surgery with concurrent radiotherapy and temozolomide.

On this page:

Terminology

Since 1926 when the term "glioblastoma multiforme" was coined, the definition of this tumor has substantially changed, particularly over the past decade with an increasing reliance on molecular markers to define these tumors.

IDH-wildtype

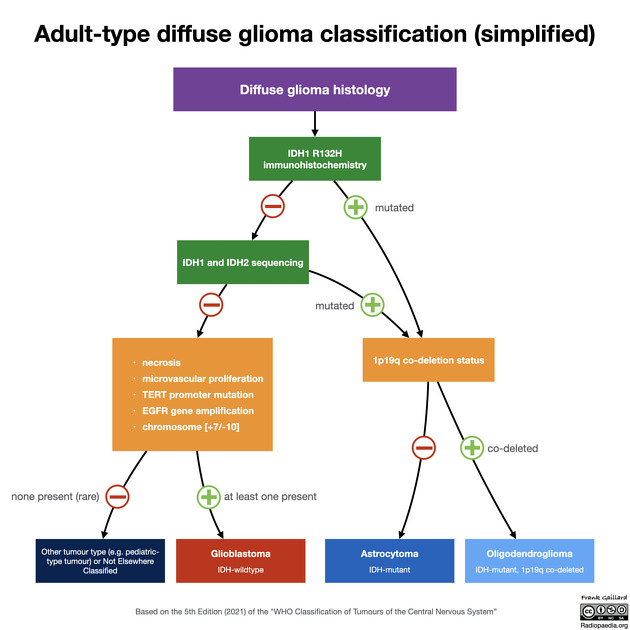

In the 5th edition (2021) of the WHO classification of CNS tumors, glioblastomas have been defined as diffuse astrocytic tumors in adults that must be IDH-wildtype, and are now an entirely separate diagnosis from astrocytoma, IDH-mutant grade 2, 3 or 4 5.

Multiforme

Glioblastoma was previously known as glioblastoma multiforme; the multiforme referred to the tumor heterogeneity. In the revised 4th edition (2016) of the WHO classification, the term "multiforme" was dropped, with these tumors referred to merely as glioblastomas. In the revised 4th edition, the abbreviation GBM was kept for disambiguation 16 however it appears to have been deprecated in the 5th edition summary 20.

Primary and secondary

Glioblastomas had traditionally been divided into primary and secondary; the former arising de novo (90%) and the latter developing from a pre-existing lower grade tumor (10%).

These historical terms now correlate closely to IDH-mutation status but should no longer be used.

Primary glioblastomas largely equate to glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype, whereas secondary glioblastomas now equate to astrocytoma, IDH-mutant, WHO CNS grade 4.

Variants

In the 5th edition (2021) WHO classification of CNS tumors, three glioblastoma histological variants are recognized (which are discussed separately), as well as a number of histological patterns which are discussed below 16.

The three recognized variants are:

Epidemiology

Glioblastomas, now defined as IDH-wildtype tumors, are essentially tumors of adults, usually occurring after the age of 40 years with a peak incidence between 65 and 75 years of age. There is a slight male preponderance with a 3:2 M:F ratio 5. White patients are affected more frequently than other ethnicities: the prevalence in Europe and North America is 3-4 per 100,000, whereas in Asia it is 0.59 per 100,000 16.

The vast majority of glioblastomas are sporadic. Rarely they are related to prior radiation exposure (radiation-induced glioma). They can also occur as part of rare inherited tumor syndromes, such as p53 mutation-related syndromes including neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Other syndromes in which glioblastomas are encountered include Turcot syndrome, Ollier disease, and Maffucci syndrome.

Clinical presentation

Typically patients present in one of three ways:

focal neurological deficit

symptoms of increased intracranial pressure

seizures

Rarely (<2%) intratumoral hemorrhage occurs and patients may present acutely with stroke-like symptoms and signs.

Diagnosis

The 5th edition (2021) of the WHO classification of CNS tumors incorporates molecular parameters into the diagnostic criteria. In this classification, to make the diagnosis of a glioblastoma the following are required 20:

adult patient

diffuse astrocytic tumor

IDH-wildtype *

-

and at least one of the following:

necrosis

microvascular proliferation

TERT promoter mutation

EGFR gene amplification

combined gain of whole chromosome 7 and loss of chromosome 10 [+7/-10]

In the rare situation where these criteria are not met, it is likely the tumor will be denoted as not elsewhere classified (NEC) although a variety of pediatric-type diffuse gliomas may be worth considering 20.

* An IDH wild-type status can be reached without the need for sequencing in patients over the age of 55 years on the basis of negative IDH-1 R132H immunohistochemistry, as the likelihood of finding other IDH mutations in older age is very unlikely 20.

Pathology

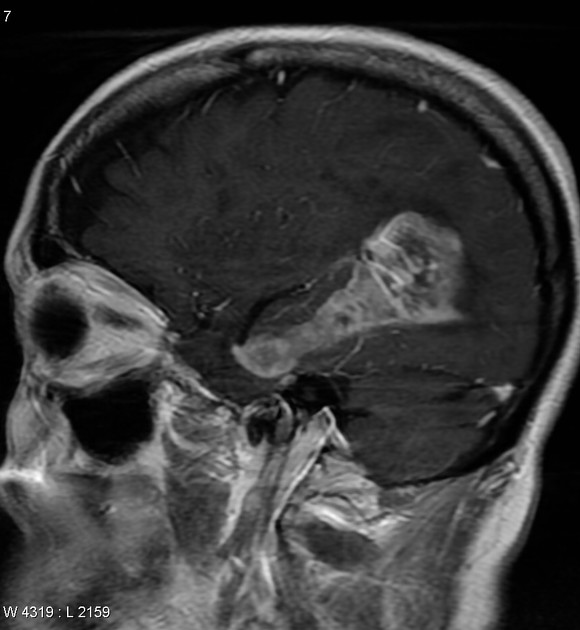

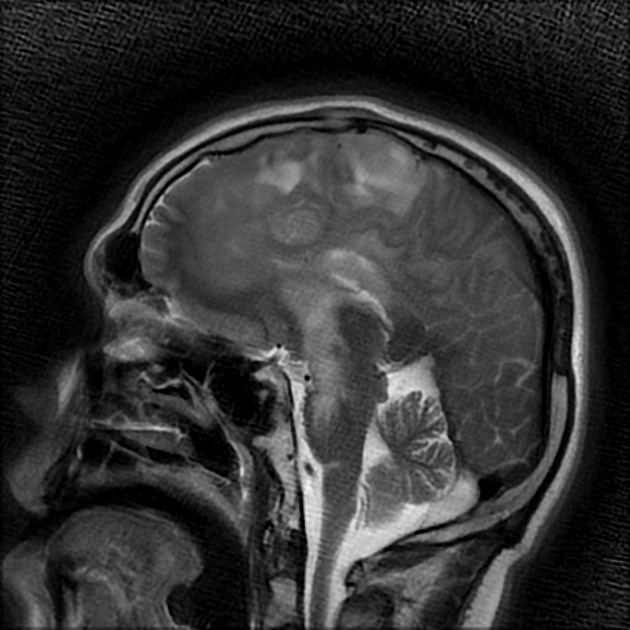

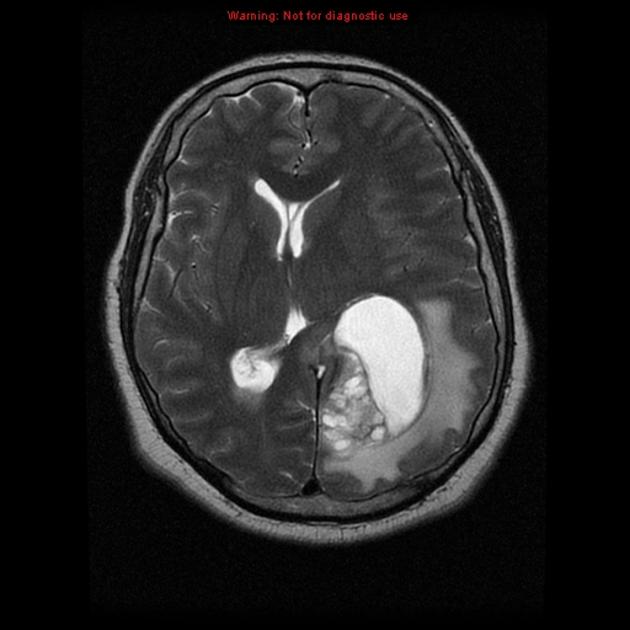

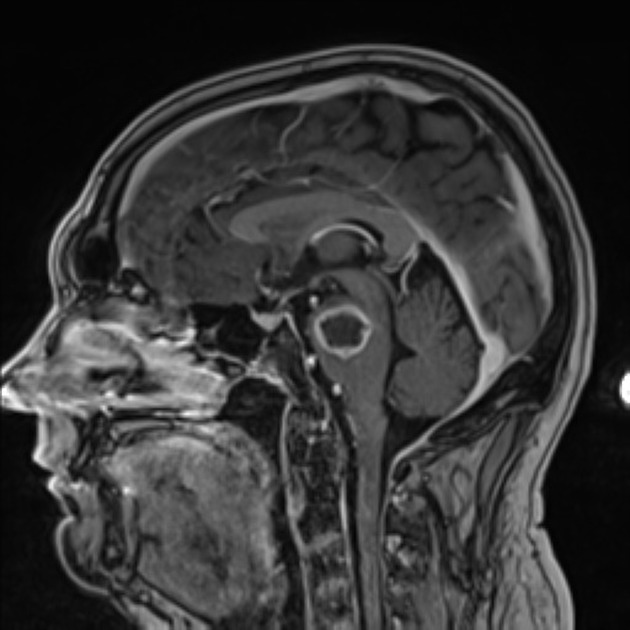

Although glioblastomas can arise anywhere within the brain, they have a predilection for the subcortical white matter and deep grey matter of the cerebral hemispheres, particularly the temporal lobe 16.

Macroscopic appearance

Glioblastomas are typically poorly marginated, diffusely infiltrating, necrotic masses localized to the cerebral hemispheres. The supratentorial white matter is the most common location.

These tumors may be firm or gelatinous. Considerable regional variation in appearance is characteristic. Some areas are firm and white, some are soft and yellow (secondary to necrosis), and others are cystic with local hemorrhage. Glioblastomas have significant variability in size from only a few centimeters to lesions that replace a hemisphere. Infiltration beyond the visible tumor margin is always present.

These tumors are multifocal in 20% of patients but are rarely truly multicentric. They may also demonstrate a gliomatosis cerebri growth pattern.

Microscopic appearance

Histologically, pleomorphic astrocytes with marked atypia and numerous mitoses are seen. Necrosis and microvascular proliferation are hallmarks of glioblastomas.

Areas of necrosis are typically surrounded by elongated cells that are arranged in parallel to each other, orthogonal to the necrotic center; this is known as pseudopalisading and is fairly unique to glioblastoma 2,20,27.

Microvascular proliferation results in an abundance of new vessels with a poorly formed blood-brain barrier (BBB) permitting the leakage of iodinated CT contrast and gadolinium into the adjacent extracellular interstitium resulting in the observed enhancement on CT and MRI respectively 11.

Edema and enhancement are however also seen in lower grade tumors that lack endovascular proliferation (such as diffuse astrocytomas, IDH-mutant) and this is thought to be due to disruption of the normal blood-brain barrier by tumor produced factors. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) for example has been shown to both disrupt tight junctions between endothelial cells and increase the formation of fenestrations 12.

Cellular variants

Glioblastomas are capable of demonstrating varied patterns, sometimes within one tumor. In addition to giant cell glioblastoma, gliosarcoma, and epithelioid glioblastoma, other histological features are sometimes encountered which impact imaging appearance and biological behavior. These include 16:

-

gemistocytes

more commonly seen in grade 4 astrocytomas

-

granular cells

histologically mimic macrophages and thus can lead to a misdiagnosis of macrophage-rich demyelination

lipidized cells

-

metaplasia

most commonly squamous epithelium

if dominant feature then a diagnosis of gliosarcoma should be considered

-

multinucleated giant cells

a common feature of glioblastoma

if they are the dominant feature then a diagnosis of giant cell glioblastoma should be considered

-

primitive neuronal cells

previously known as glioblastoma with PNET-like component

more frequently has CSF spread

MYC or MYCN amplification common

IDH-mutant in 15-20% of cases

-

small cell glioblastoma

histologically appears similar to oligodendroglioma, but usually demonstrate EGFR amplification

like oligodendrogliomas, they have a predilection for extensive cortical involvement

Immunophenotype

GFAP: positive but of variable intensity

S100: positive

nestin: positive

p53 protein: positive if TP53 mutated

EGFR: positive in 40-98% of cases 16

IDH-1 R132H: negative (by definition, otherwise not an IDH-wildtype glioblastoma, but rather an astrocytoma, IDH-mutant WHO CNS grade 4) 16

H3 K27M mutation: negative (if positive then diffuse midline glioma H3 K27-altered)

Genetics

combined gain of whole chromosome 7, loss of chromosome 10 [+7/-10]

alterations of the CDK4/6–RB1 cell-cycle pathway: 80% due to deletions of CDKN2A 20

Radiographic features

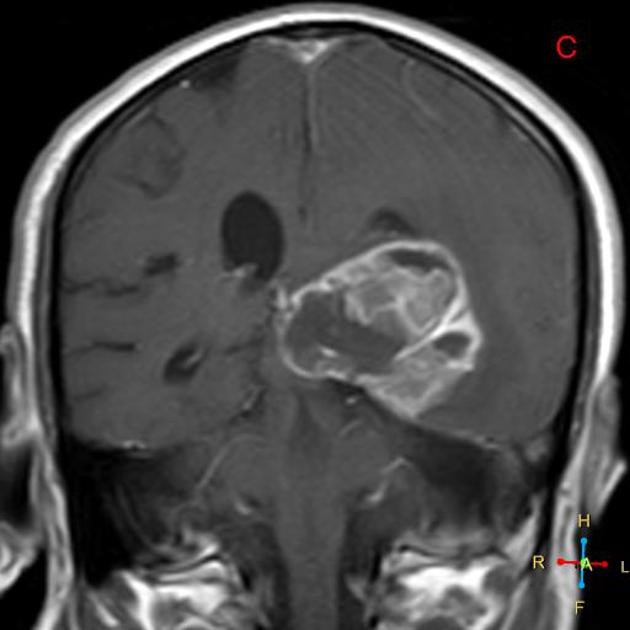

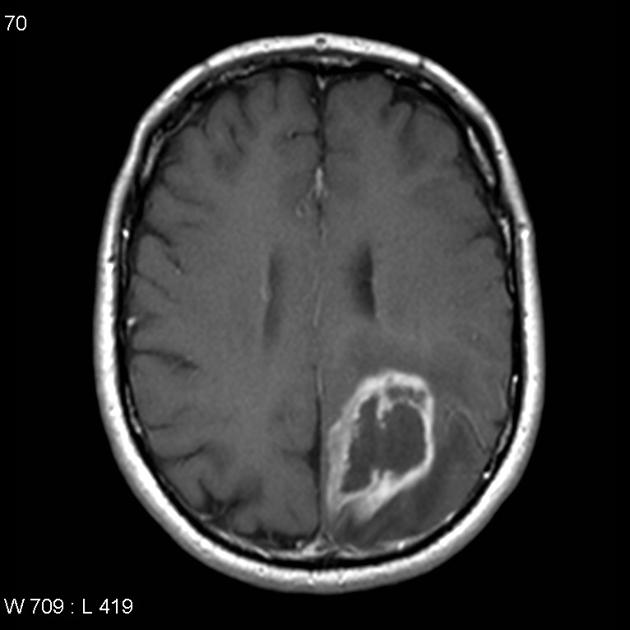

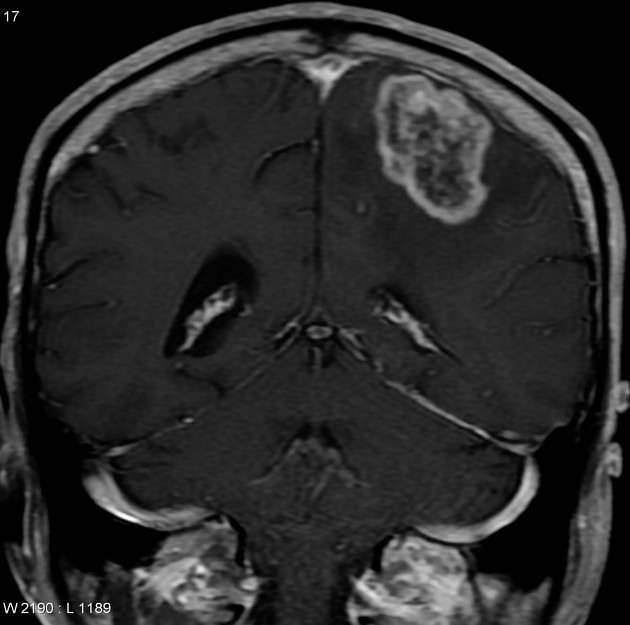

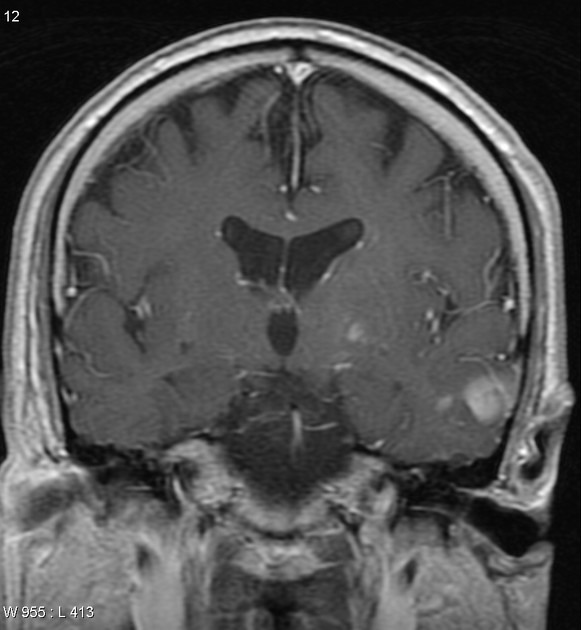

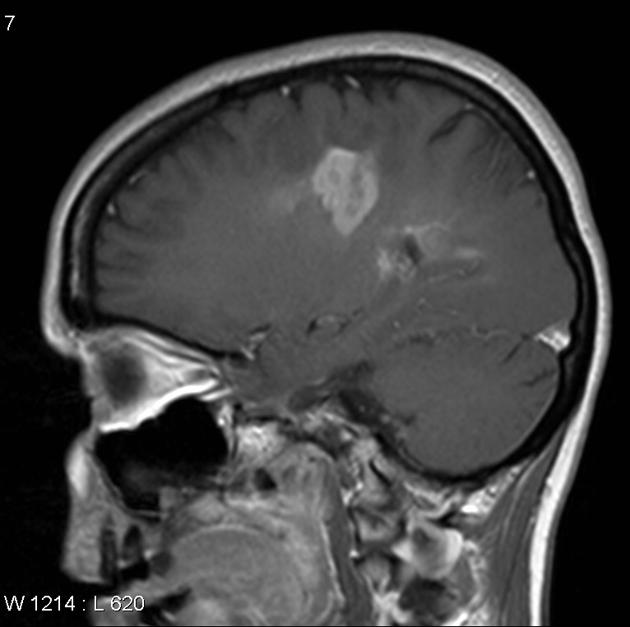

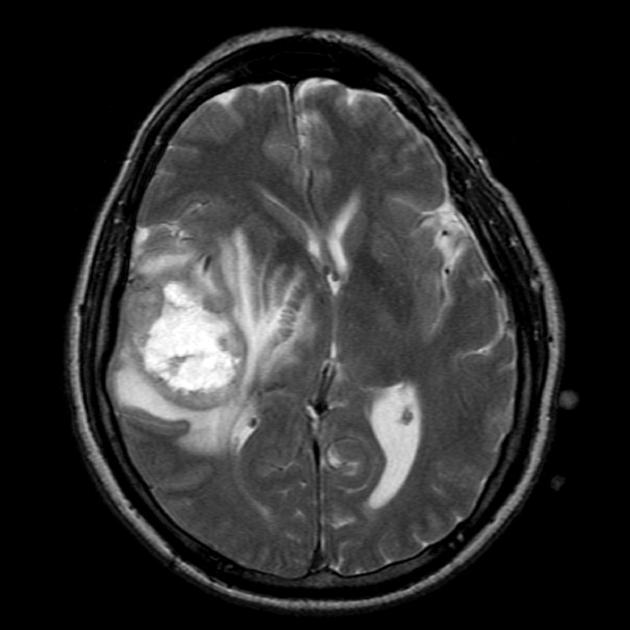

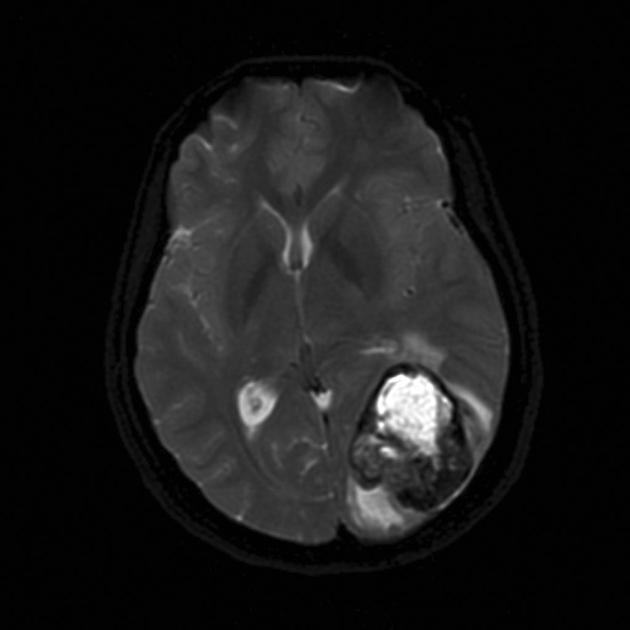

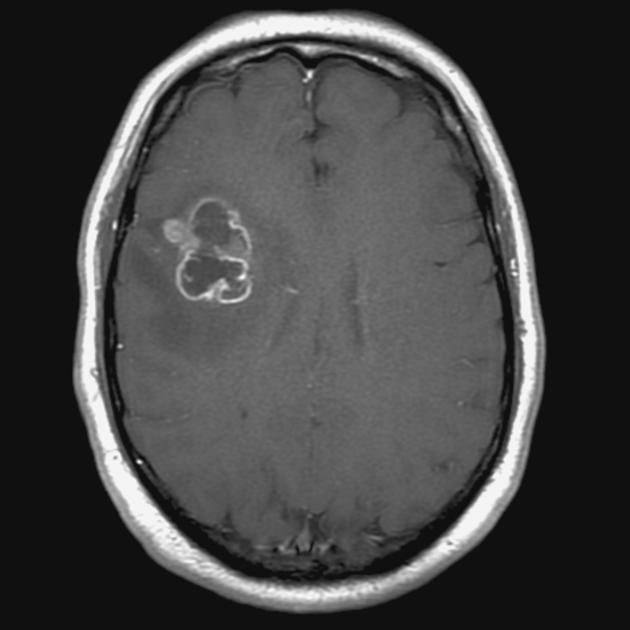

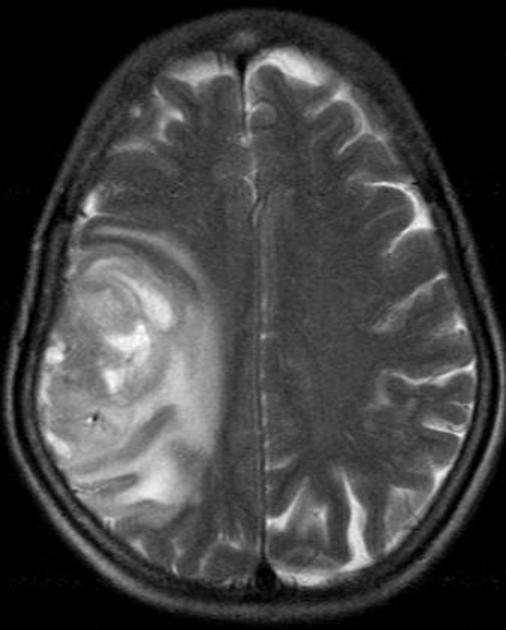

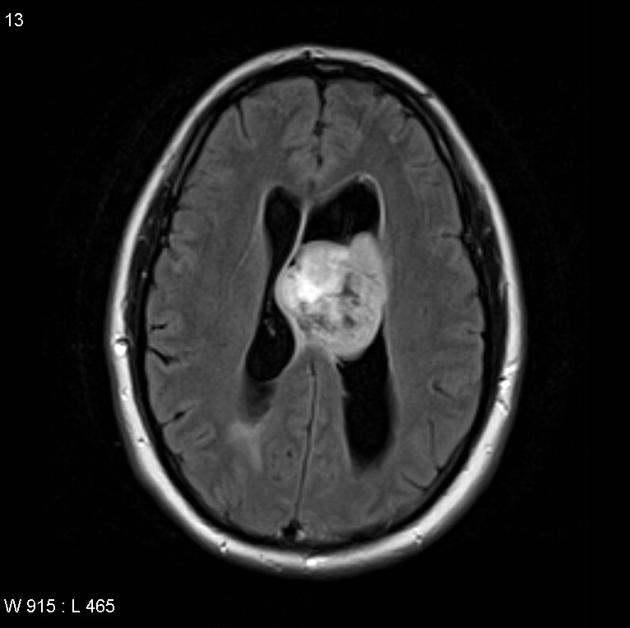

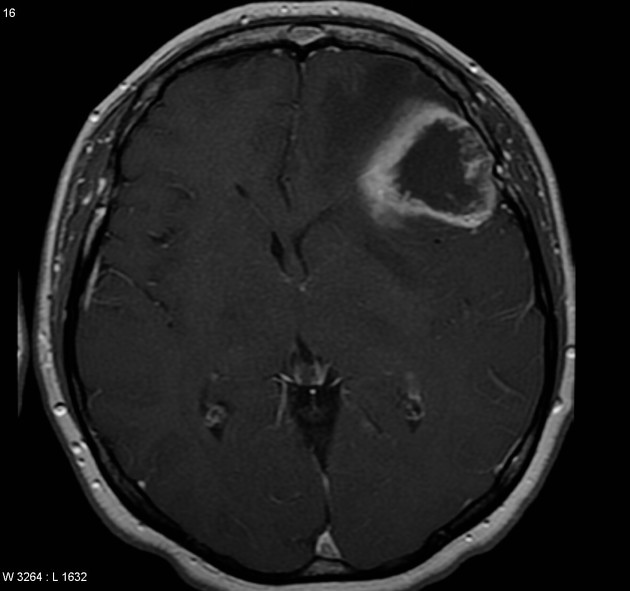

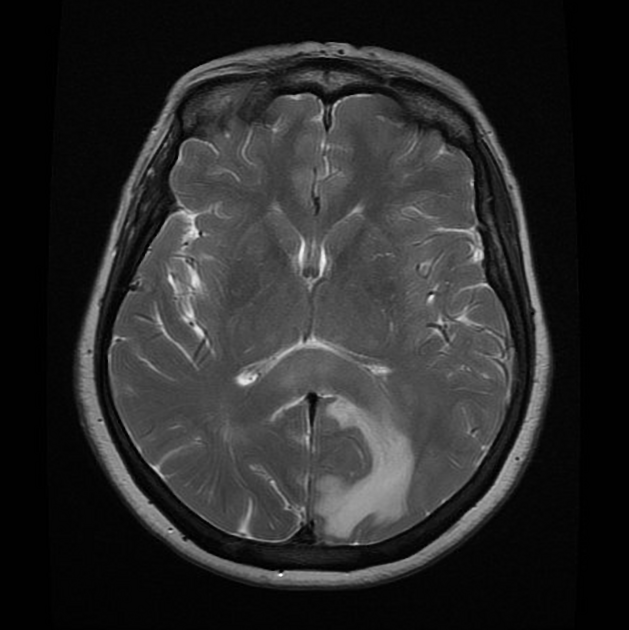

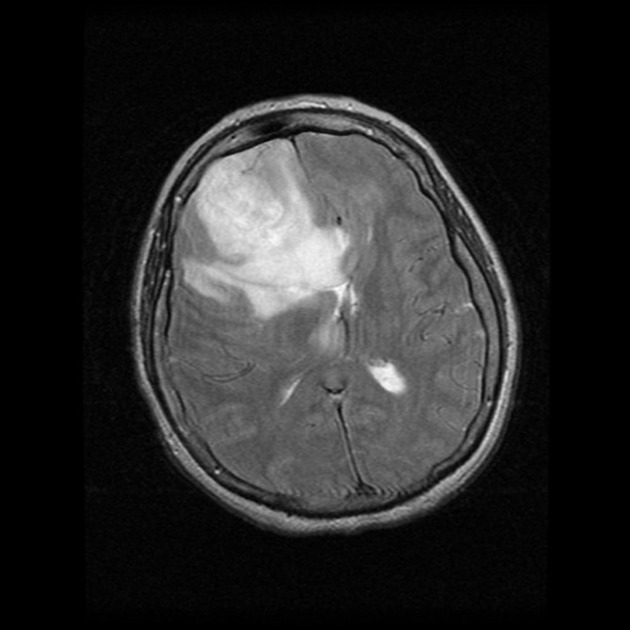

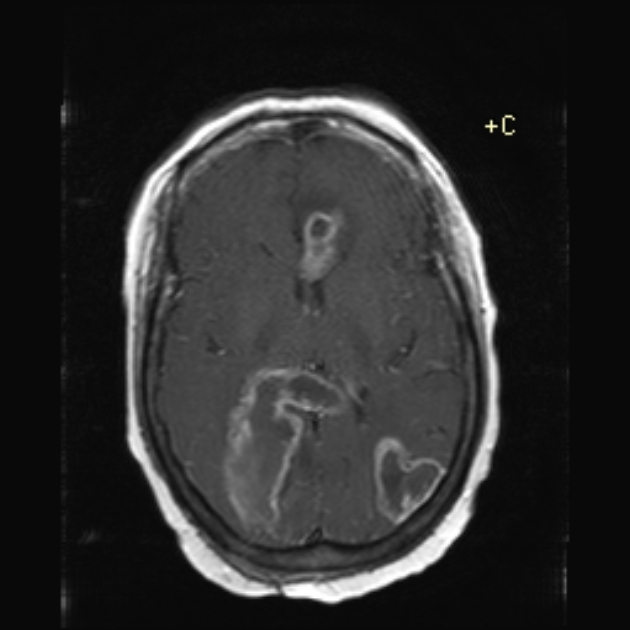

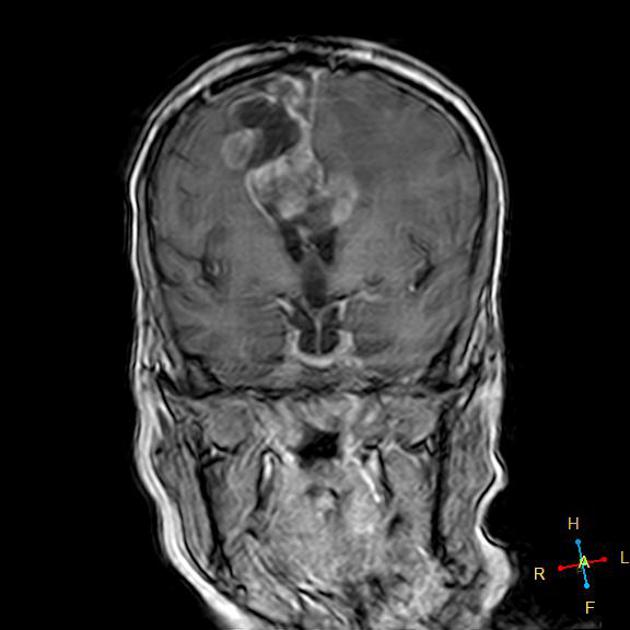

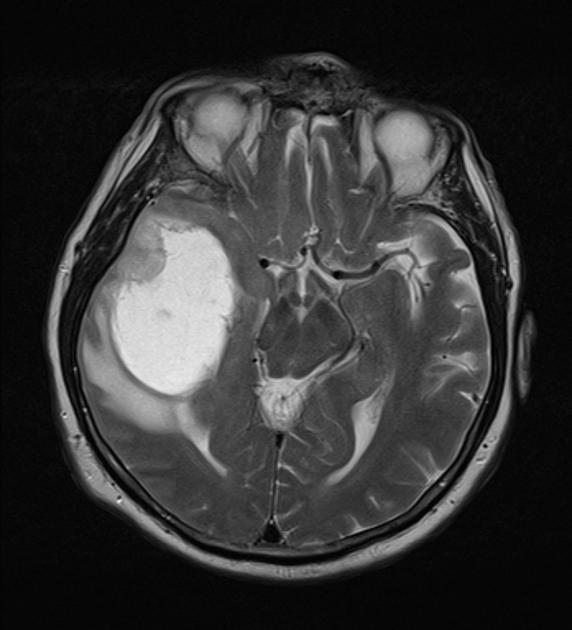

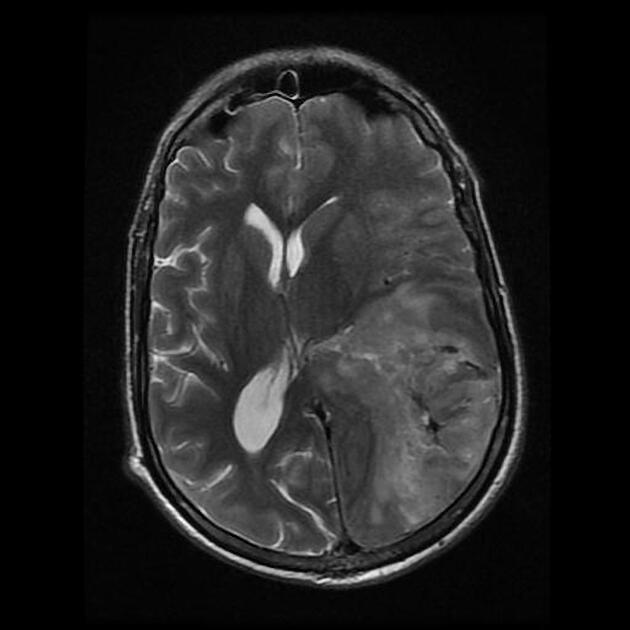

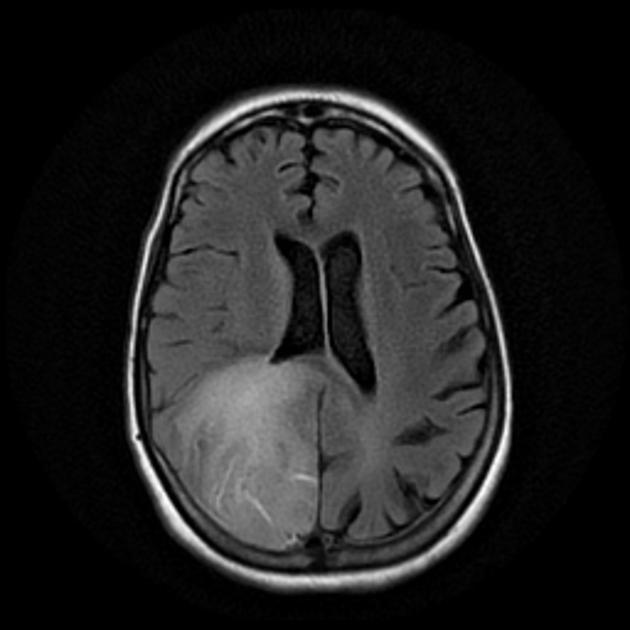

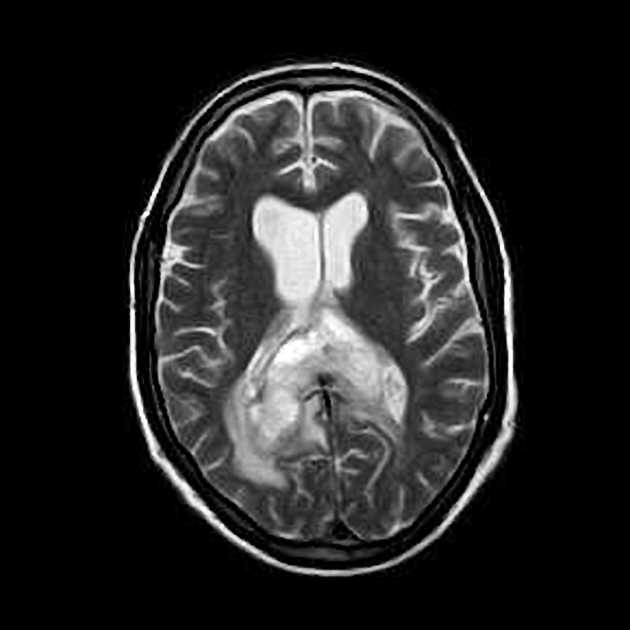

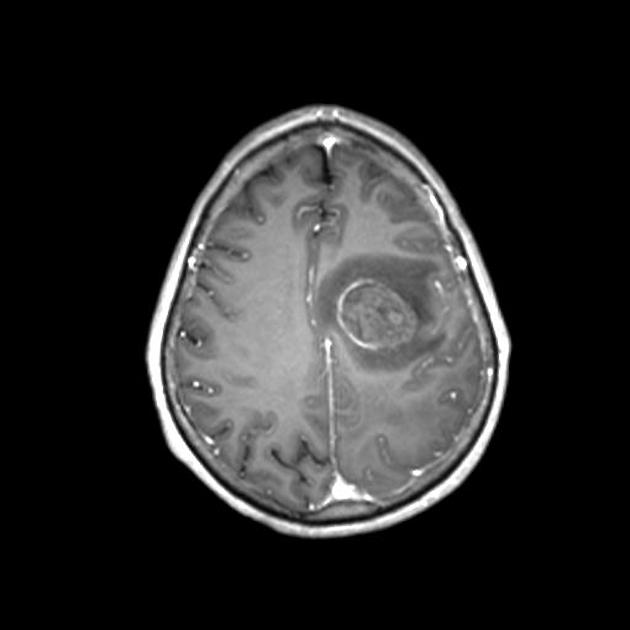

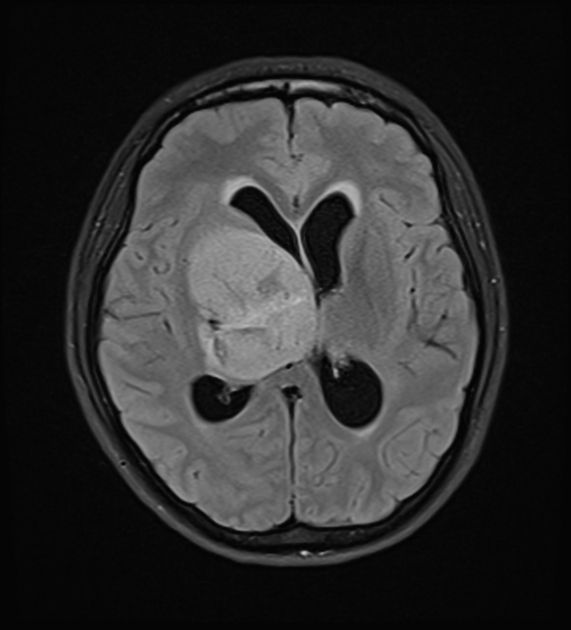

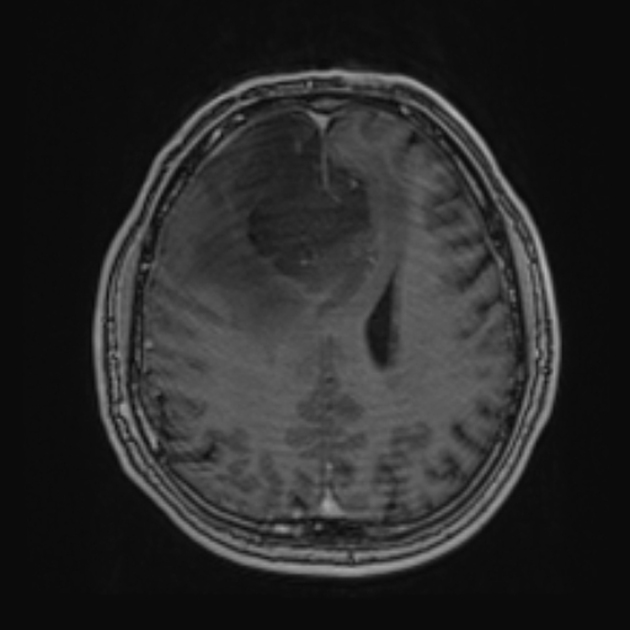

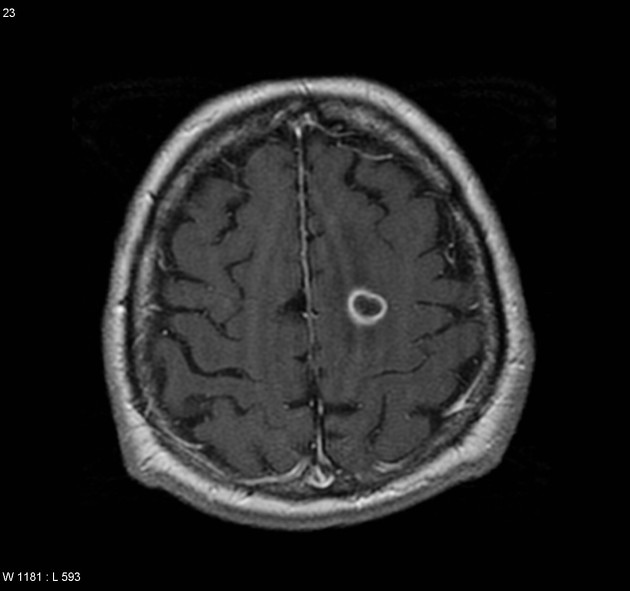

Glioblastomas are typically large tumors at diagnosis. They often have thick, irregularly enhancing margins and a central necrotic core, which may also have a hemorrhagic component. They are surrounded by vasogenic-type edema, which in fact usually contains infiltration by neoplastic cells.

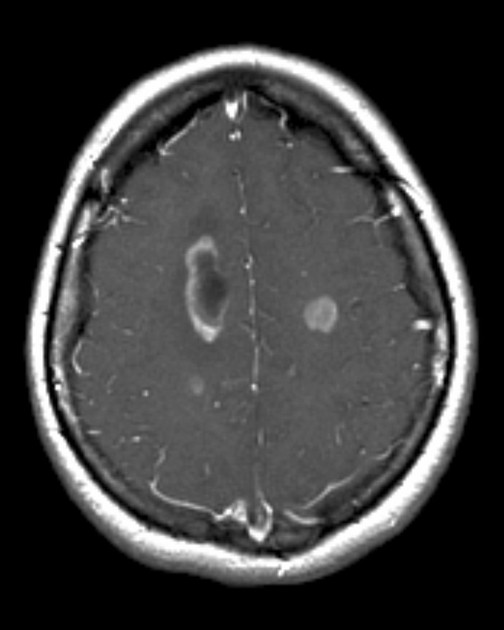

Multifocal disease, which is found in ~20% of cases, is where multiple areas of enhancement are connected to each other by abnormal white matter signal, which represents microscopic spread to tumor cells. Multicentric disease, on the other hand, is where no such connection can be seen.

It is important to note that molecular glioblastoma will have imaging features similar to, if not indistinguishable from, low grade astrocytoma, IDH-mutant.

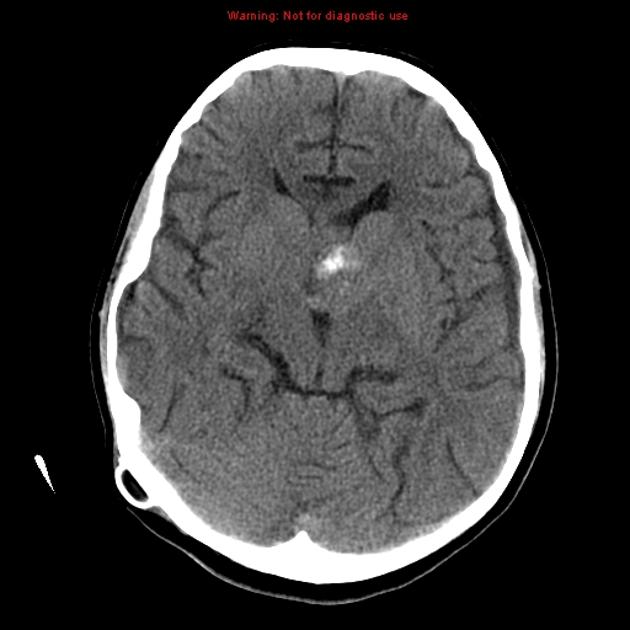

CT

irregular thick margins: iso- to slightly hyperattenuating (high cellularity)

irregular hypodense center representing necrosis

marked mass effect

surrounding vasogenic edema

hemorrhage is occasionally seen

calcification is uncommon

intense irregular, heterogeneous enhancement of the margins is almost always present

MRI

-

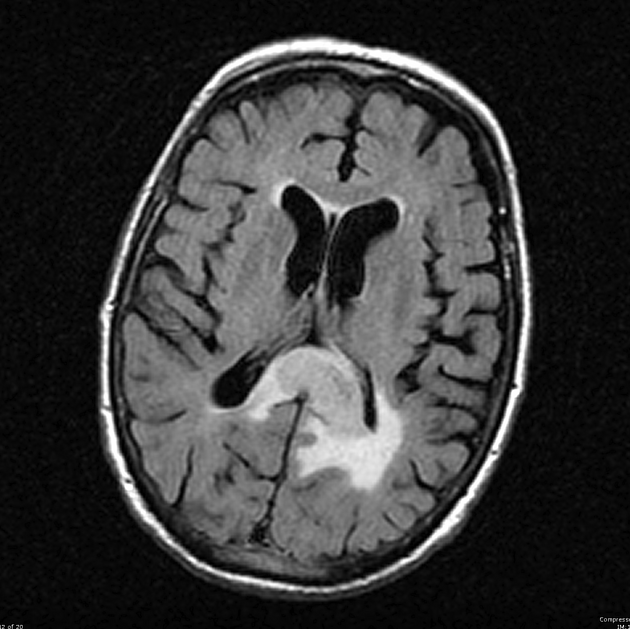

T1

hypo to isointense mass within the white matter

central heterogeneous signal (necrosis, intratumoral hemorrhage)

-

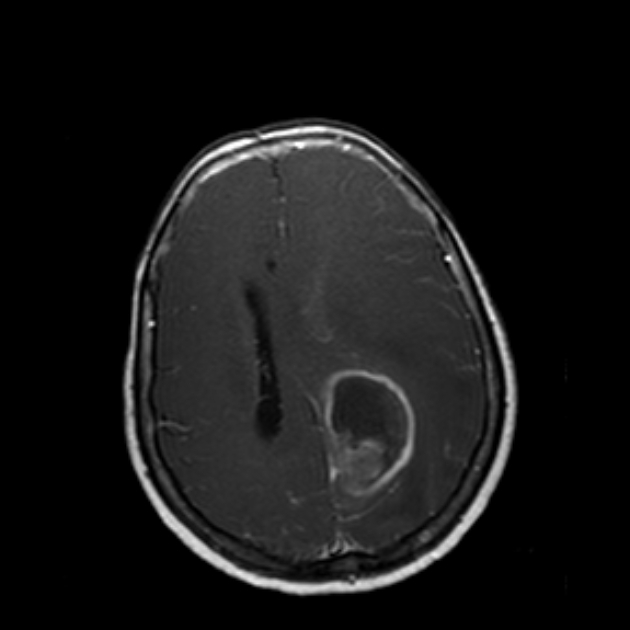

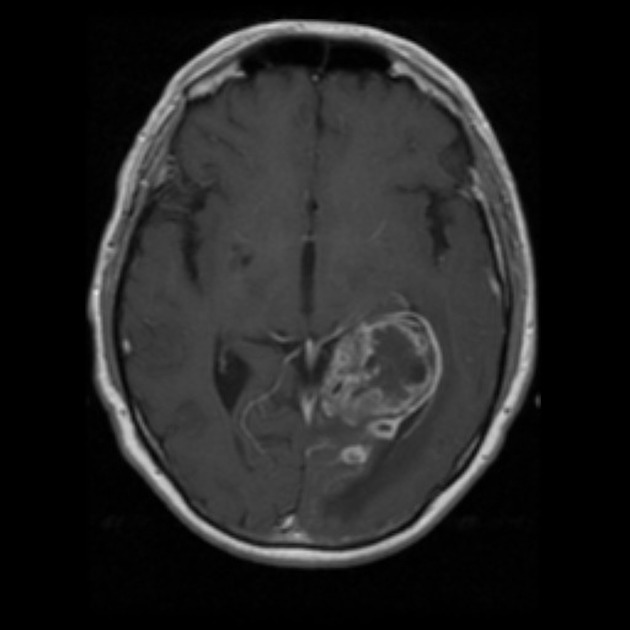

T1 C+ (Gd)

enhancement is variable but is almost always present

typically peripheral and irregular with nodular components

usually surrounds necrosis

-

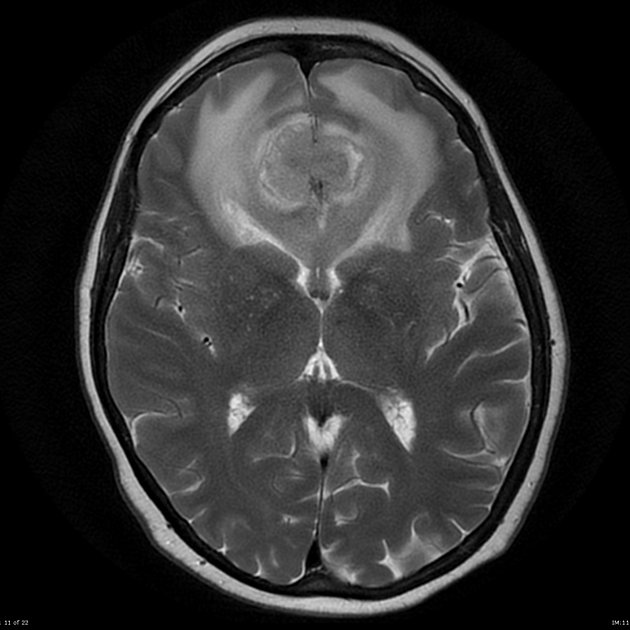

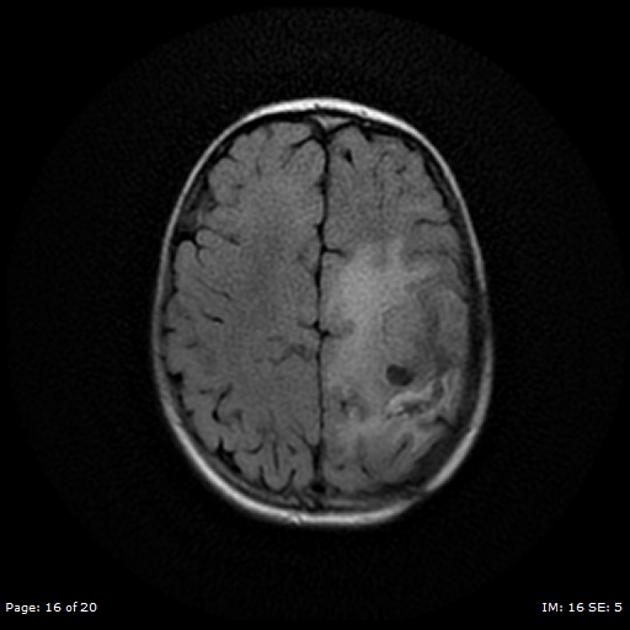

T2/FLAIR

hyperintense

surrounded by vasogenic edema

flow voids are occasionally seen

lacks T2/FLAIR "mismatch" sign

-

GE/SWI

susceptibility artifact on SWI, also called “intratumoral susceptibility signals”, are usually due to microvascular proliferation and microhemorrhage 33

susceptibility artifact due to calcification are rare

-

low-intensity rim from blood products 6

incomplete and irregular in 85% when present

mostly located inside the peripheral enhancing component

absent dual rim sign

-

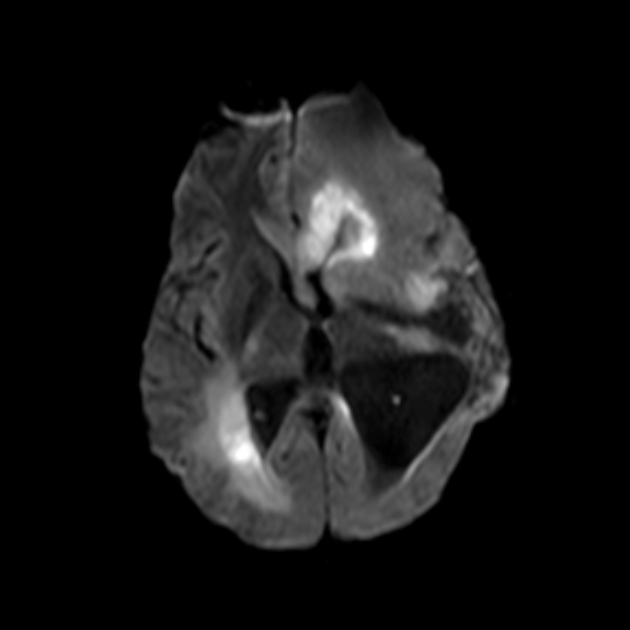

DWI/ADC

-

solid component

elevated signal on DWI is common in the solid/enhancing component

ADC values are typically similar to normal white matter (745 ± 135 x 10-6 mm2/s 13), but significantly lower than surrounding vasogenic edema which has facilitated diffusion

-

central necrotic component

facilitated diffusion (ADC values >1000 x 10-6 mm2/s)

care must be taken in interpreting cavities with blood product

-

MR perfusion: rCBV elevated compared to lower grade tumors and normal brain

-

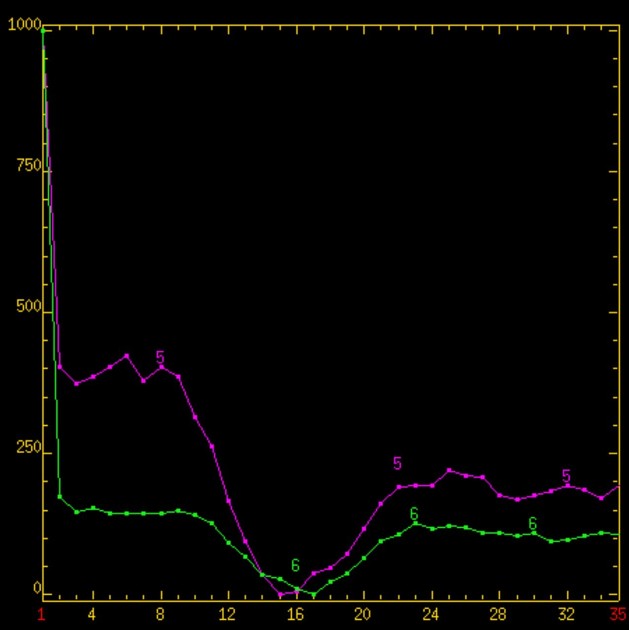

MR spectroscopy

-

typical spectroscopic characteristics include

choline: increased

lactate: increased

lipids: increased

NAA: decreased

myo-inositol: decreased

-

PET

PET demonstrates the accumulation of FDG (representing increased glucose metabolism) which typically is greater than or similar to metabolism in grey matter.

Radiogenomics

A number of features are seen to correlate with molecular marker status, such as MGMT promoter methylation, which typically demonstrates:

high ADC values

limited surrounding edema

low CBV

This has a sensitivity of 79% (95% CI, 72-85%) and specificity of 78% (95% CI, 71-84%) 19.

Radiology report

When reporting a new diagnosis of a mass that is likely a glioblastoma, it is useful to include:

-

morphology

size in three dimensions

presence and degree of central necrosis

non-enhancing tumor involving cortex, deep grey or white matter: look at ADC for lower values

-

relationship to/involvement of

major white matter tracts

large vessels

-

extension

across midline

into brainstem

subependymal spread

CSF dissemination

Treatment and prognosis

Surgery

Maximal safe resection remains an important first step, not only debulking the tumor and reducing symptoms of raised intracranial pressure but also providing tissue for formal diagnosis and assessment of molecular features.

Traditionally the focus of resection has been removal of all enhancing tissue. This has been shown to result in improved survival 25. More recently, there is increased interest in "supramaximal resection" whereby not only is the component that is contrast-enhancing resected, but also adjacent non-enhancing tumor 25.

More complete surgical resection can be aided by the use intraoperative MRI and 5-ALA fluorescence-guided surgery 26.

Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy

Following surgery, postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy (temozolomide) is the most common treatment (Stupp protocol). Other, often second-line, therapies include lomustine (in combination with temozolamide in patients with MGMT methylated tumors), antiangiogenesis agents (e.g. bevacizumab), immunotherapy, and CAR-T cell therapy 28,29.

Although in individuals less than 70 years of age a standard Stupp protocol is usual, in older individuals the optimum treatment regimen is less well established 15,21. This is particularly the case in the very elderly or those with significant comorbidities 21. In such cases, surgical resection has less marked survival benefit. Radiotherapy is usually administered as a shorter course (e.g. 25-40 Gy in 5-15 daily fractions, rather than 60 Gy over 6 weeks), but even in this setting adding temozolomide significantly increases survival, especially in MGMT methylated (inactive) tumors 15,21.

Prognosis

Despite substantial advances, even in the best-case scenario, glioblastoma carries a poor prognosis with a median survival of <2 years 15.

Negative prognostic factors include:

increased necrosis 10

greater enhancement 10

deep location (e.g. thalamus)

MGMT not-methylated

increased age

lower pre-diagnosis functional status (e.g. ECOG performance status)

TERT promoter mutation (controversial) 31

EGFR amplification 30-32

combined chromosome 7 gain/chromosome 10 loss 30,32

Follow-up

Glioblastomas should be followed up closely with MRI.

Immediate post-operative imaging

Generally a scan is obtained within 24-48 hours of surgery to assess residual disease. Early scanning is necessary to avoid post-operative enhancement that can make interpretation difficult. It should be noted, however, that some post-operative enhancement can occur within the first day post surgery 22 and therefore it is essential that these scans are interpreted alongside the pre-operative scan.

Ongoing imaging

Although timing and frequency will vary between institutions and treating surgeons/oncologists typically scans are obtained every 8 to 12 weeks. In individuals who have no residual macroscopic disease and remain stable for a protracted time, the frequency of follow-up imaging can be gradually decreased. In contrast, sometimes it is worthwhile performing an earlier scan to problem-solve ambiguous imaging features.

The primary aims of on-going follow-up are:

identify tumor progression and complications

distinguish tumor progression from pseudoprogression

distinguish pseudoresponse from tumor progression

Response assessment criteria

Glioblastomas have been the subject of close trial scrutiny with many new chemotherapeutic agents showing promise. As such a number of criteria have been created over the years to assess response to treatment. The response assessment in neuro-oncology (RANO) criteria are most widely used. Other historical systems are worth knowing to allow the interpretation of older data. These systems for response criteria for first-line treatment of glioblastomas include 9:

RANO criteria (most commonly used today)

History and etymology

The original term glioblastoma multiforme was coined in 1926 by Percival Bailey and Harvey Cushing; the suffix multiforme was given to describe the various appearances of hemorrhage, necrosis, and cysts.

Differential diagnosis

General imaging differential considerations include:

-

astrocytoma, IDH-mutant WHO CNS grade 4

may appear very similar/indistinguishable

generally younger patients

T2/FLAIR mismatch sign is common and highly specific 23

-

may look identical

both may appear multifocal

metastases usually are centered on grey-white matter junction and spare the overlying cortex

rCBV in the "edema" will be reduced

-

should be considered especially in patients with AIDS, as in this setting central necrosis is more common

otherwise usually homogeneously enhancing

-

central restricted diffusion is helpful, however, if glioblastoma is hemorrhagic then the assessment may be difficult

presence of smooth and complete SWI low-intensity rim 6

presence of dual rim sign 6

-

can appear similar

often has an open ring pattern of enhancement

usually younger patients

-

subacute cerebral infarction

history is essential in suggesting the diagnosis

should not have elevated choline

should not have elevated rCBV

-

especially in patients with AIDS

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.