The pancreas is uncommonly injured in blunt trauma. However, pancreatic trauma has a high morbidity and mortality rate.

On this page:

Epidemiology

The pancreas is injured in ~7.5% (range 2-13%) of blunt trauma cases 1,3,7. Motor vehicle accidents account for the vast majority of cases. Penetrating trauma constitutes up to a third of cases in some studies 7.

Clinical presentation

The classic triad of fever, raised white cell count, and amylase is rare. Serum amylase or lipase are elevated in ~80% of cases 1 but distinguishing between a raised amylase or lipase as an acute phase reactant or resulting from a pancreatic injury is difficult.

Non specific clinical signs are a seat belt sign or flank hematoma.

Pathology

The pancreatic body accounts for two-thirds of injuries with ~10% occurring each in the head, neck, and tail 1. Due to its retroperitoneal location and oblique course, it is prone to compression against the vertebral column 1-3,7.

Due to the course of the main pancreatic duct, it may be injured in trauma to any part of the pancreas.

Terminology

Various terminology may be employed 1-3,7:

pancreatic contusion: indistinct region of parenchymal edema

laceration: discrete linear or branching partial thickness tear

pancreatic transection: full-thickness tear

pancreatic comminution (fracture): shattered pancreas

pancreatic hematoma

For the AAST grading system of injuries, the proximal pancreas is defined as the gland to the right of the SMV-portal vein axis whereas the distal pancreas is to the left of the axis.

Grading

See main article: grading of pancreatic injuries.

Associations

It is uncommonly (<10%) an isolated injury and other organs that are also injured include (in decreasing order of frequency 7):

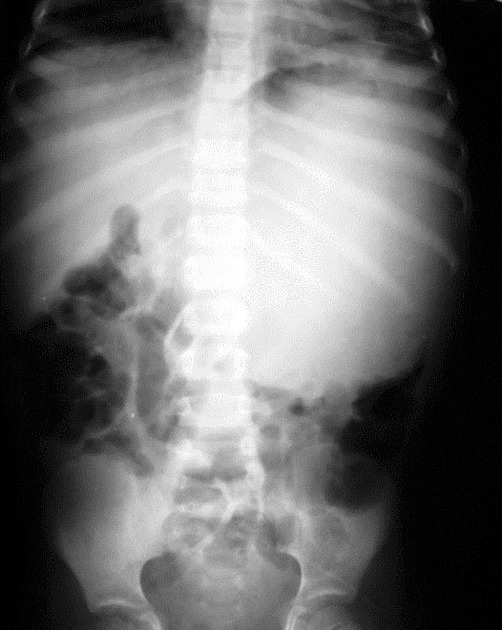

Radiographic features

Fluoroscopy

ERCP can be used to image the pancreatic duct and any associated injury, although its main role is to provide access to stent the pancreatic duct when injury is confirmed by MRCP

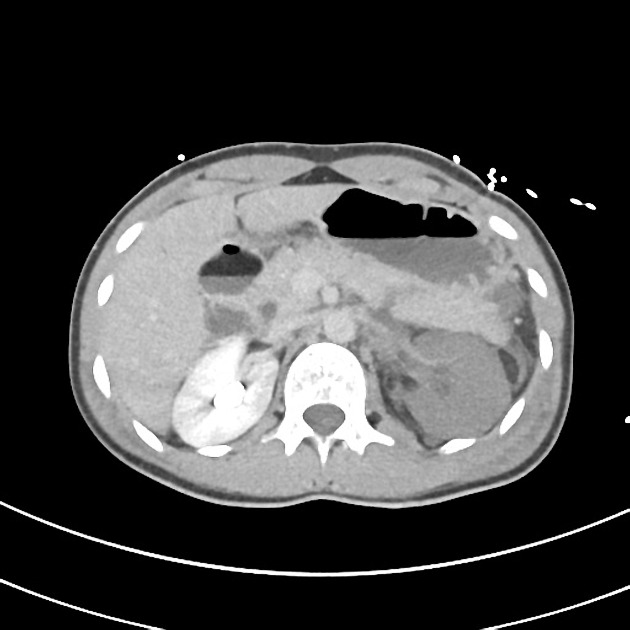

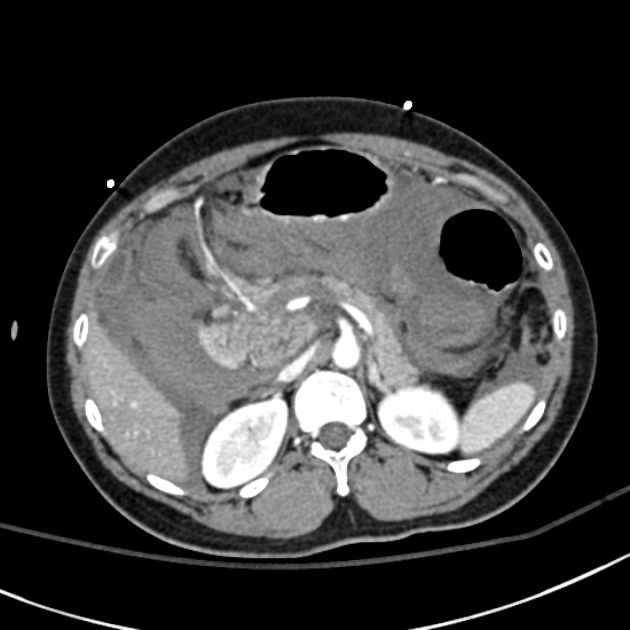

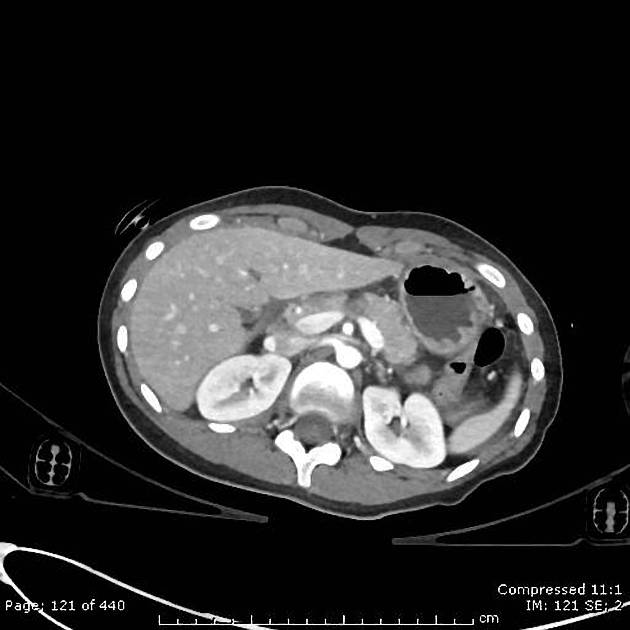

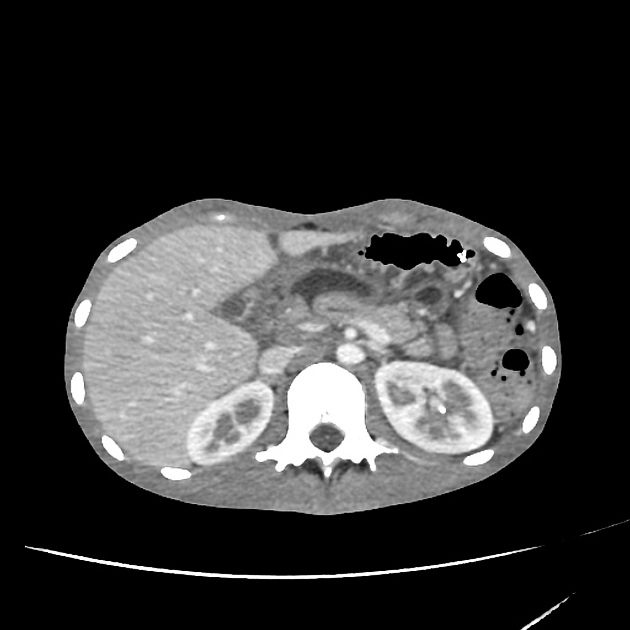

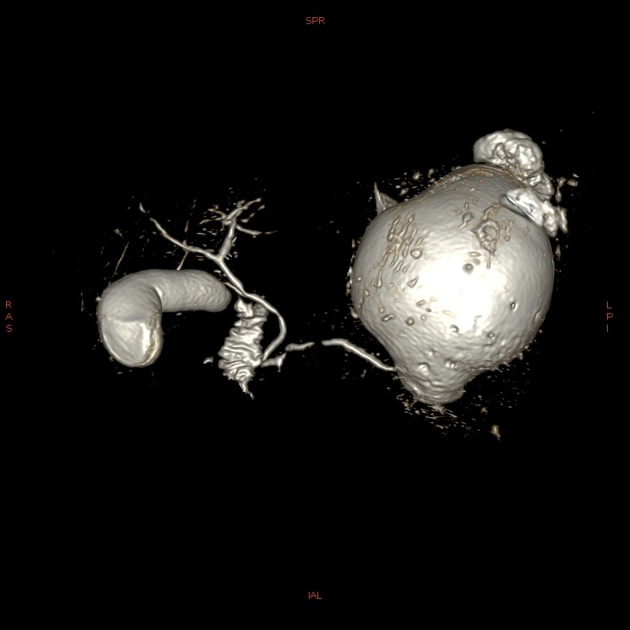

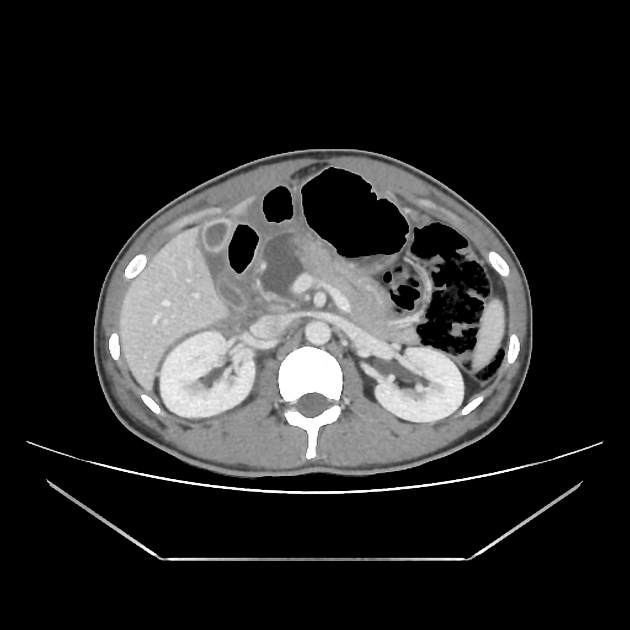

CT

CT is the initial modality of choice in assessment of injuries to the abdomen. The portal venous phase is most commonly used however some trauma centers advocate for an additional arterial phase 7.

-

direct signs 1,2,7

hypodense laceration or comminution of the pancreatic parenchyma

transection

heterogeneous parenchymal enhancement

enlargement of the pancreas

hematoma

fluid collections (pseudocyst or abscess) communicating with the pancreatic duct

-

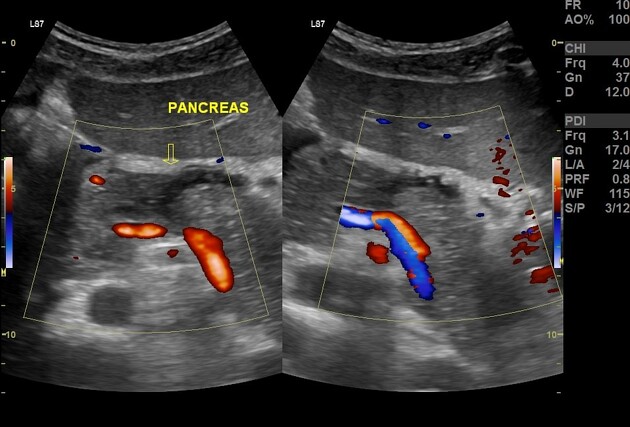

secondary signs

peripancreatic fat stranding, fluid or hematoma between the pancreas and splenic vein 1,2

thickening of the anterior pararenal (Gerota) fascia

peripancreatic retroperitoneal fluid

intraperitoneal fluid, especially in the lesser sac

adjacent injuries e.g. spleen, liver, biliary, and duodenum

injury to the pancreatic duct may not be seen directly but is inferred by the grading of the injury 1

Low monoenergetic (monoE) reconstruction on spectral scanners has been shown to increase injury diagnostic accuracy 7,8.

MRI

MRCP can be used to image the pancreatic duct and any associated injury

Treatment and prognosis

Delayed diagnosis raises both the mortality and morbidity of traumatic pancreatic injuries, both of which are high, with a mortality rate of up to 20% 3.

Injuries with pancreatic duct disruption are more likely to undergo endoscopic stenting whereas surgical intervention such as wide drainage, and distal pancreatectomy is preferred for grade III to V injuries 1,9.

Complications

Complications of pancreatic trauma occur in up to 20% of patients and are more likely in higher grade injuries. Complications include:

pancreatitis: occurs in ~7.5% (range 6-10%)

fistula (more common with pancreatic duct disruption)

abscess and sepsis (more common with pancreatic duct disruption)

-

hemorrhage

from the pancreas

from a pseudoaneursym (e.g. splenic or gastroduodenal artery)

Differential diagnosis

pancreatic clefts which are most prominent at the junction of the body and neck 6

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.