Ovarian dermoid cyst and mature cystic ovarian teratoma are terms often used interchangeably to refer to the most common ovarian neoplasm. These slow-growing tumors contain elements from multiple germ cell layers and can be assessed with ultrasound or MRI.

On this page:

Terminology

Although they have very similar imaging appearances, ovarian dermoid cyst and mature cystic ovarian teratoma have a fundamental histological difference: a dermoid is composed only of ectodermal elements, whereas teratomas also comprise mesodermal and endodermal elements.

For the sake of simplicity, both are discussed in this article, as much of the literature combines the two entities.

Epidemiology

Mature cystic teratomas account for ~15% (range 10-20%) of all ovarian neoplasms. They tend to be identified in young women, typically around the age of 30 years 1, and are also the most common ovarian neoplasm in patients younger than 20 years 7.

Clinical presentation

Uncomplicated ovarian dermoid tend to be asymptomatic and are often discovered incidentally. They do, however, predispose to ovarian torsion, and may then present with acute pelvic pain.

Pathology

Mature cystic teratomas are encapsulated tumors with mature tissue or organ components. They are composed of well-differentiated derivations from at least two of the three germ cell layers (i.e. ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm). They, therefore, contain developmentally mature skin complete with hair follicles and sweat glands, sometimes luxuriant clumps of long hair, and often pockets of sebum, blood, fat (93%) 10, bone, nails, teeth, eyes, cartilage, and thyroid tissue. Typically their diameter is smaller than 10 cm, and rarely more than 15 cm. Real organoid structures (teeth, fragments of bone) may be present in ~30% of cases.

Location

They are bilateral in 10-15% of cases 1,2.

Variants

struma ovarii tumor: contains thyroid elements, however, sometimes these are separately classified as specialized teratomas of the ovaries

Radiographic features

Plain radiograph

May show calcific and tooth components within the pelvis.

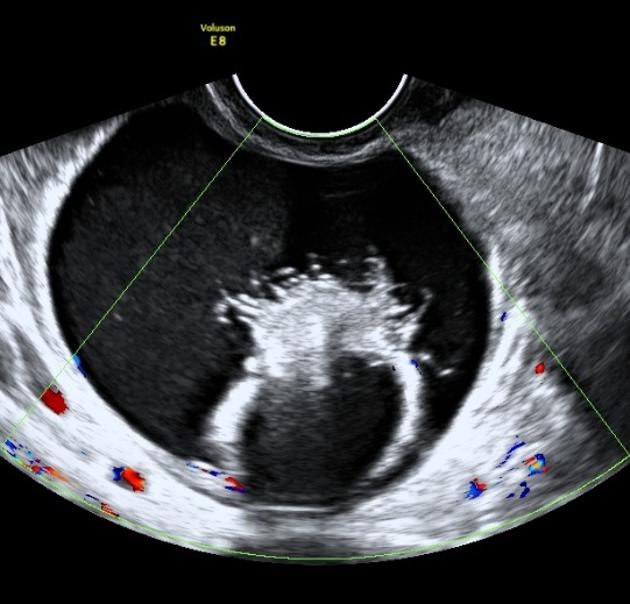

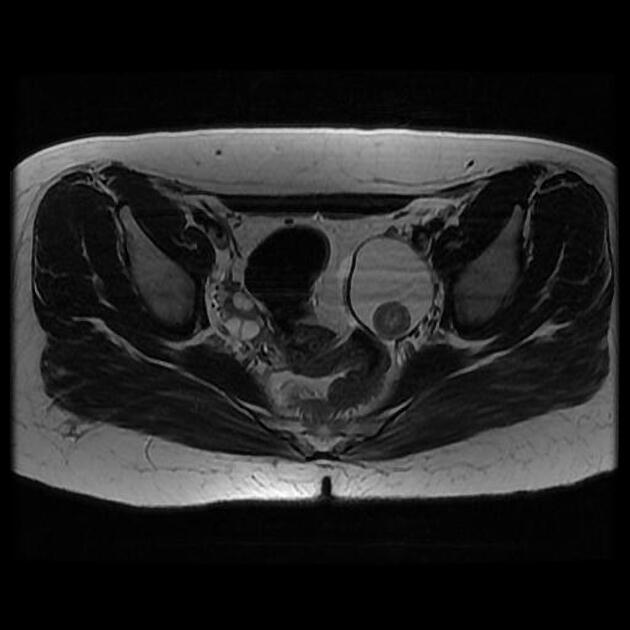

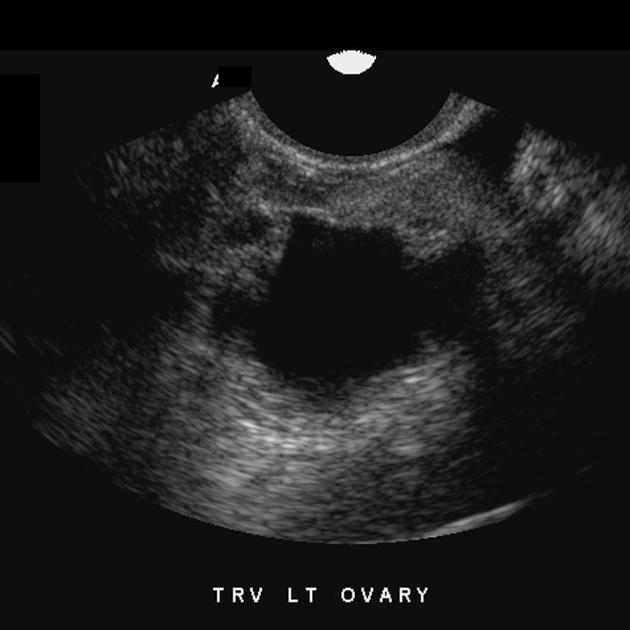

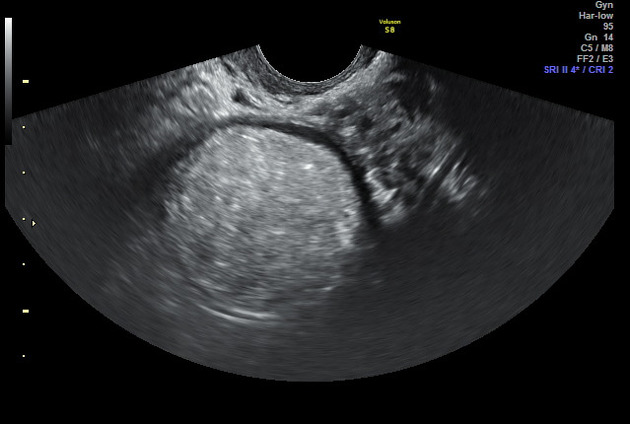

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is the preferred imaging modality. Typically an ovarian dermoid is seen as a cystic adnexal mass with some mural components. Most lesions are unilocular.

The spectrum of sonographic features includes:

-

diffusely or partially echogenic mass with posterior sound attenuation owing to sebaceous material and hair within the cyst cavity

an echogenic interface at the edge of mass that obscures deep structures: the tip of the iceberg sign

mural hyperechoic Rokitansky nodule (dermoid plug)

echogenic, shadowing calcific or dental (tooth) components

the presence of fluid-fluid levels 5

multiple thin, echogenic bands caused by the hair in the cyst cavity: the dot-dash pattern (dermoid mesh)

-

color Doppler: no internal vascularity

internal vascularity requires further workup to exclude a malignant lesion

intracystic floating balls sign is uncommon but characteristic 9

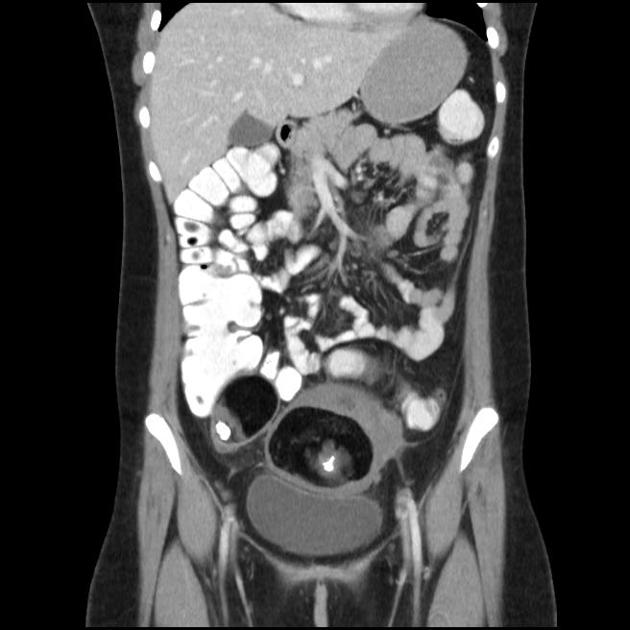

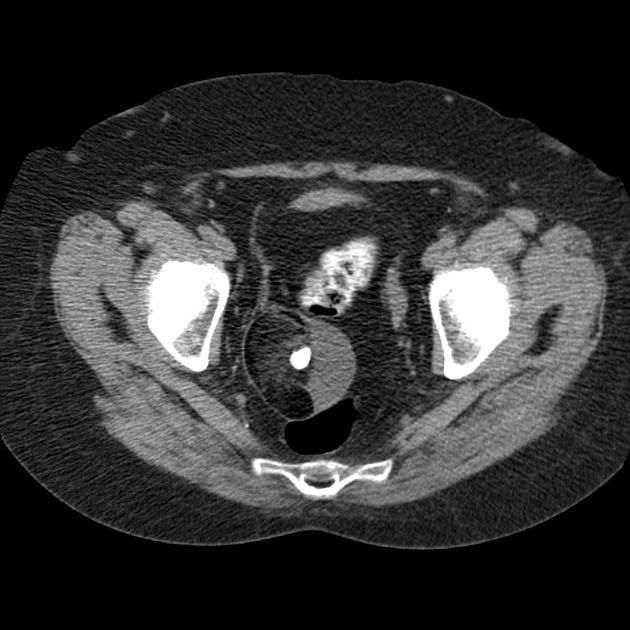

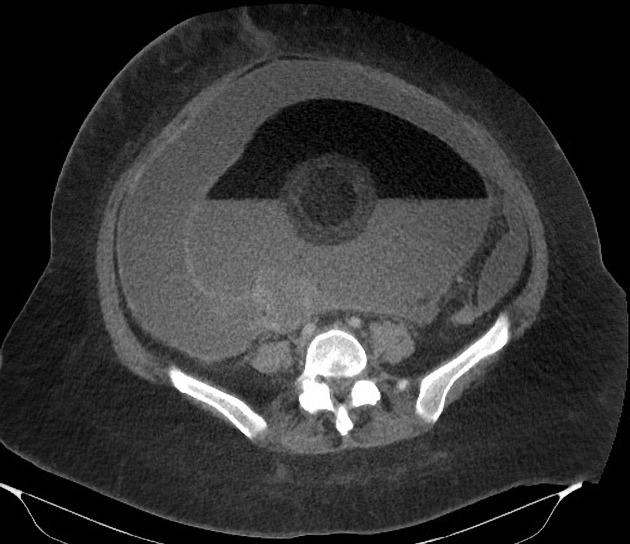

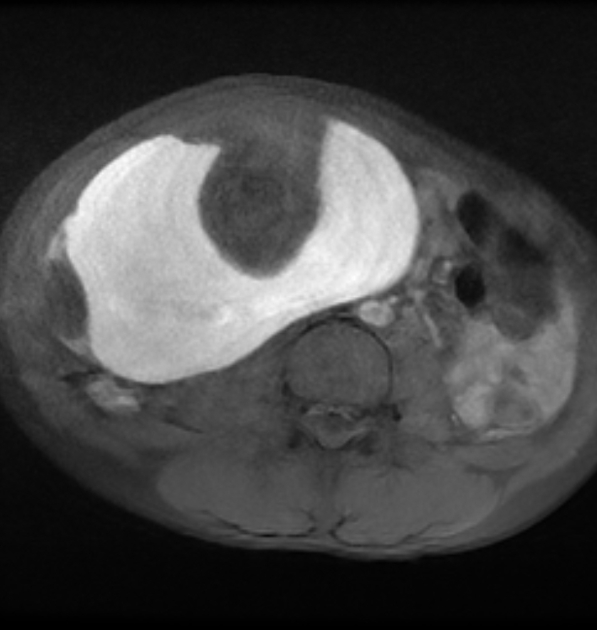

CT

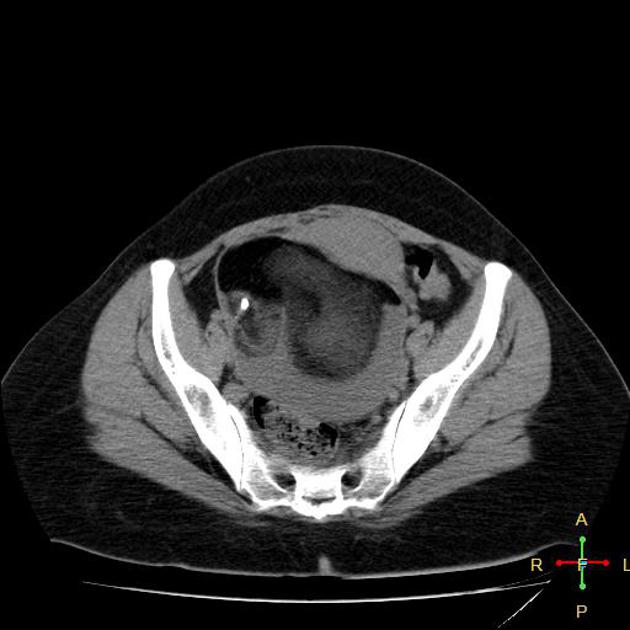

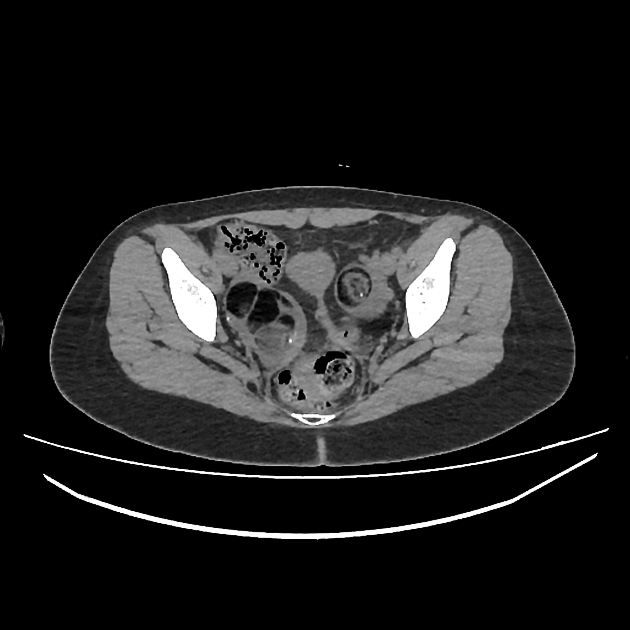

CT has high sensitivity in the diagnosis of cystic teratomas 6 though it is not routinely recommended for this purpose owing to its ionizing radiation.

Typically CT images demonstrate fat (areas with very low Hounsfield values), fat-fluid level, calcification (sometimes dentiform), Rokitansky protuberance, and tufts of hair. The presence of most of the above tissues is diagnostic of ovarian cystic teratomas in 98% of cases 5. Whenever the size exceeds 10 cm or soft tissue plugs and cauliflower appearance with irregular borders are seen, malignant transformation should be suspected 5.

When ruptured, the characteristic hypoattenuating fatty fluid can be found as anti dependant pockets, typically below the right hemidiaphragm, a pathognomonic finding 2. The escaped cyst content also leads to chemical peritonitis and the mesentery may be stranded and the peritoneum thickened, which may mimic peritoneal carcinomatosis 2.

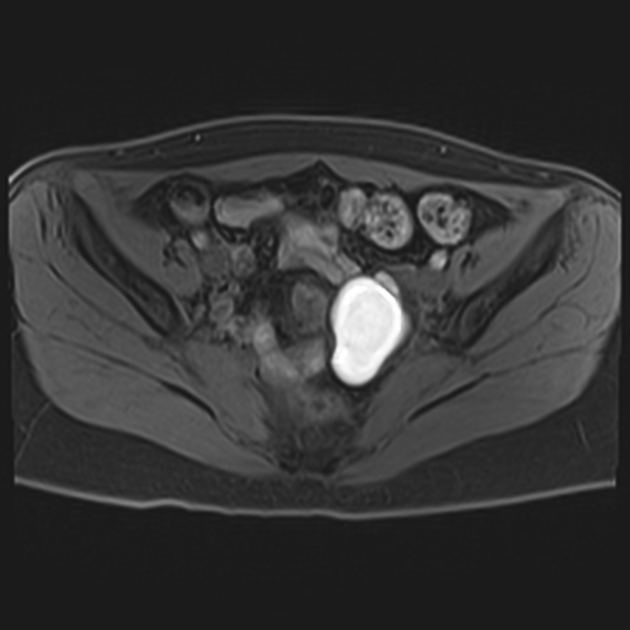

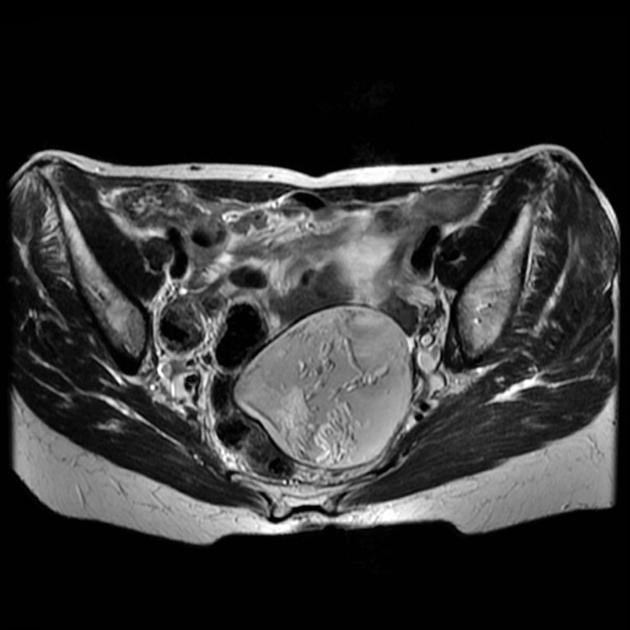

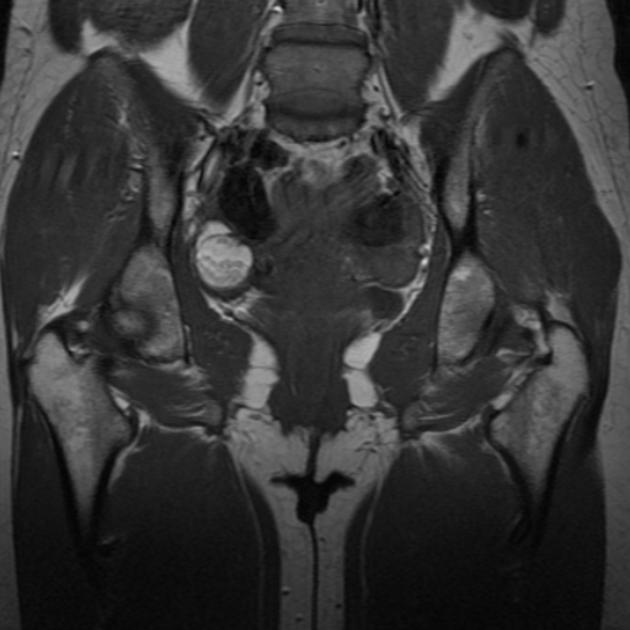

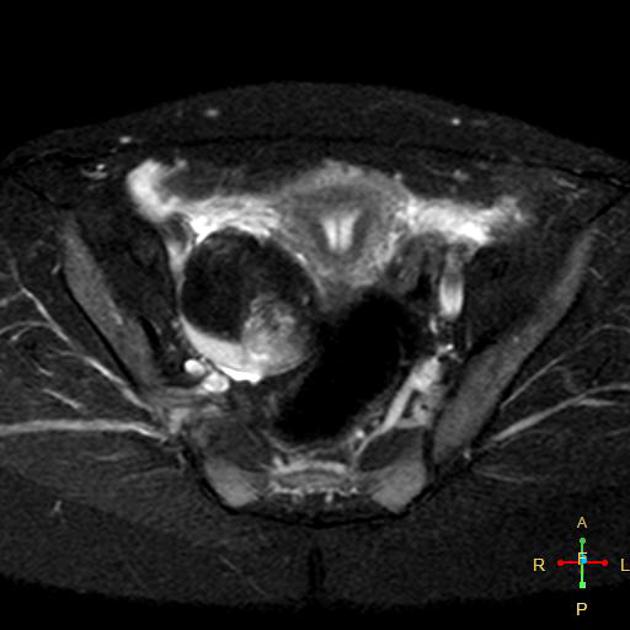

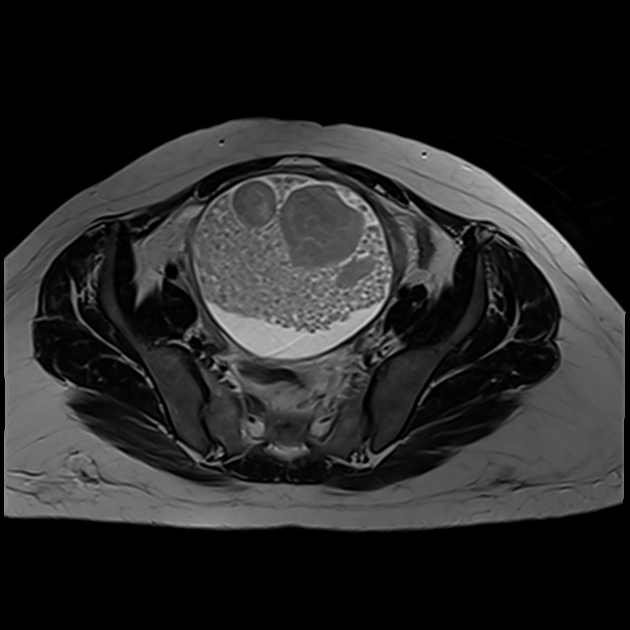

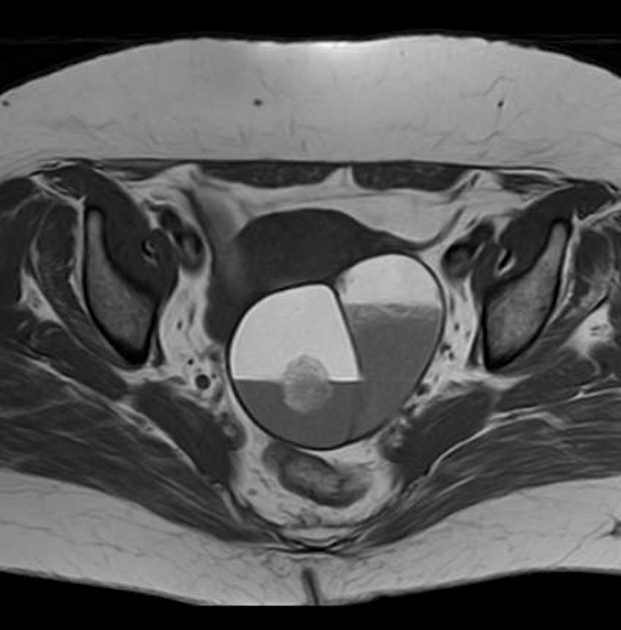

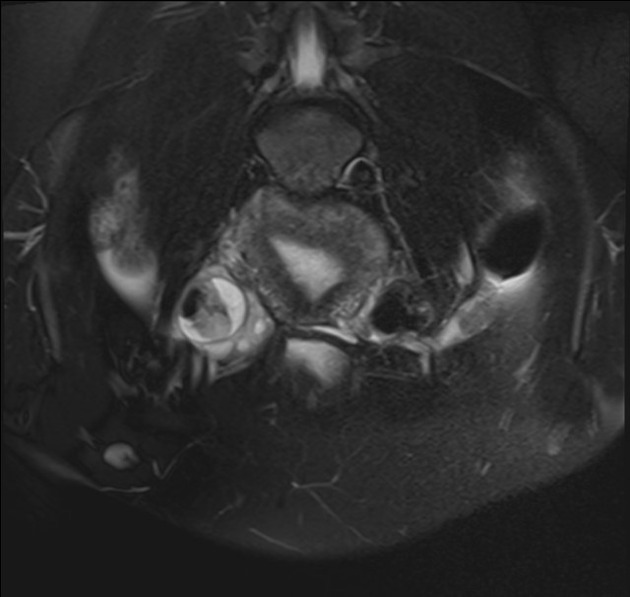

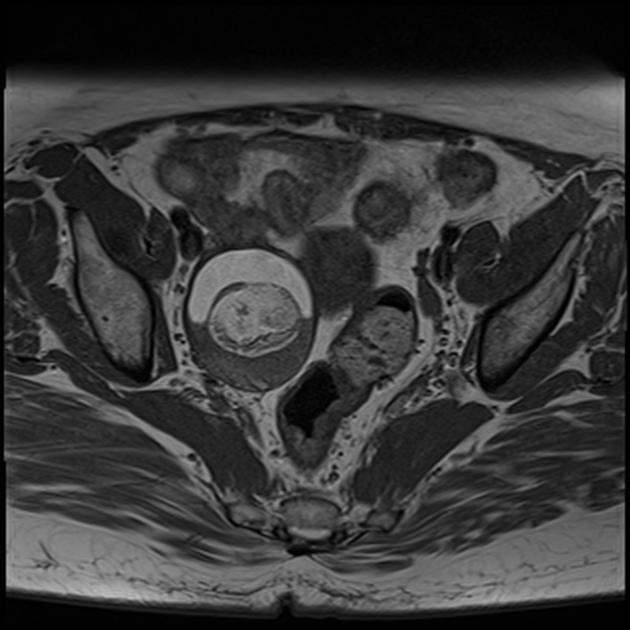

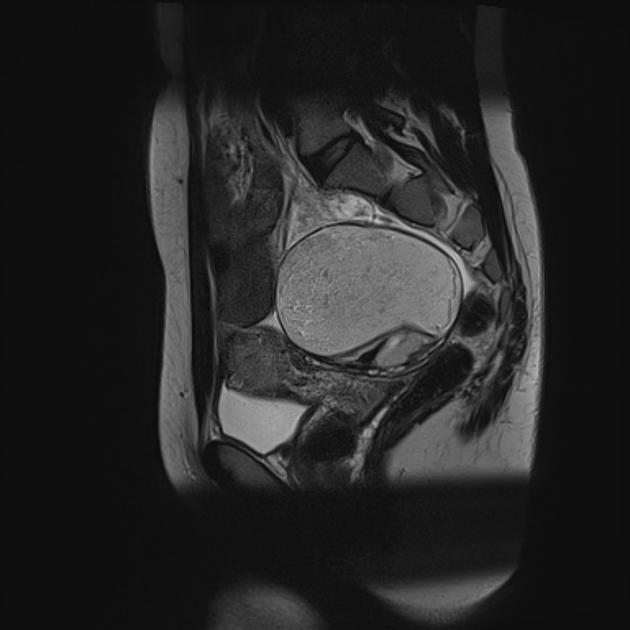

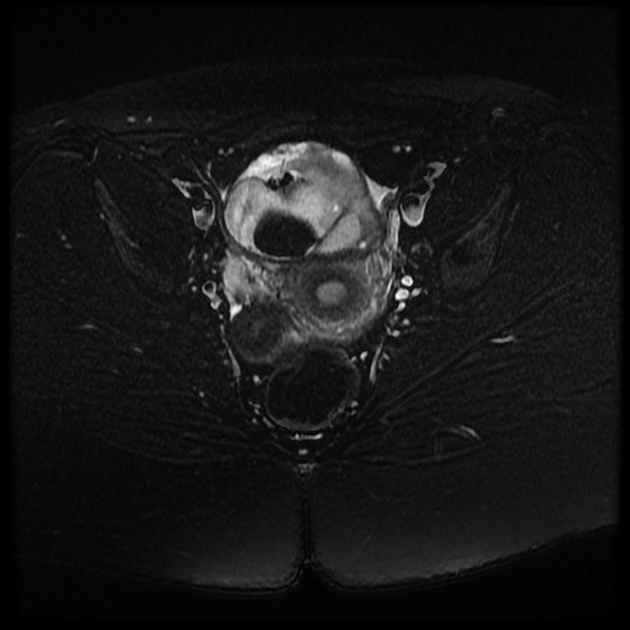

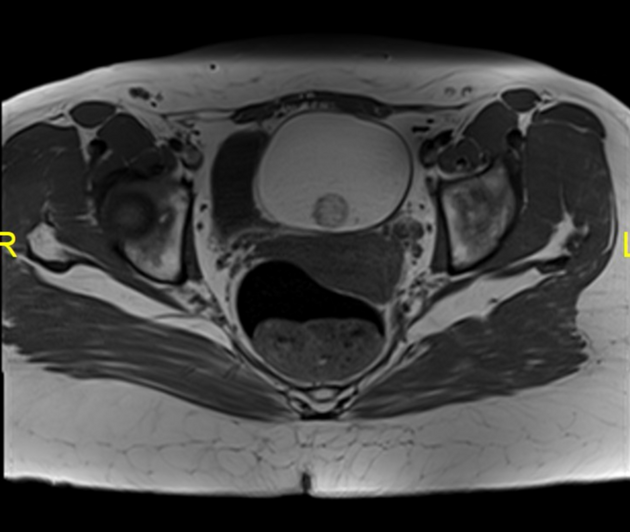

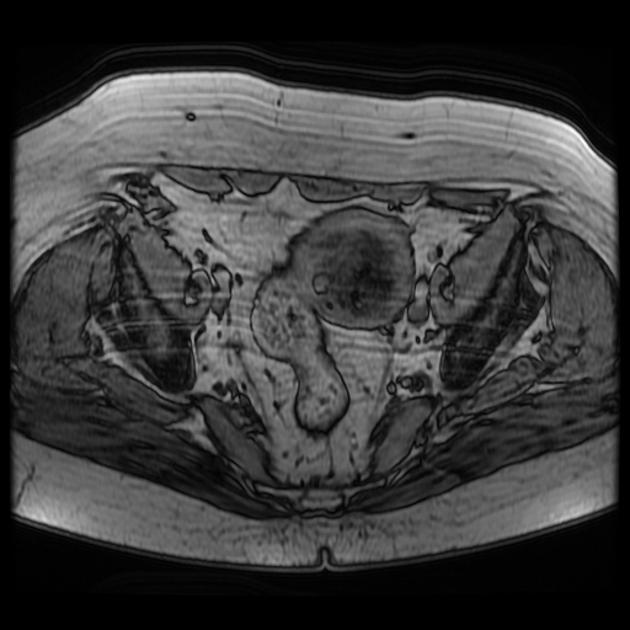

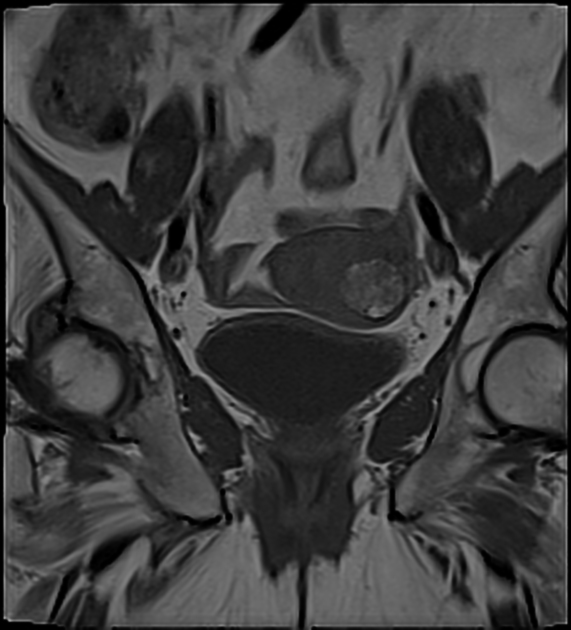

MRI

MR evaluation usually tends to be reserved for difficult cases but is exquisitely sensitive to fat components. Both fat suppression techniques and chemical shift artifact can be used to confirm the presence of fat.

Enhancement is also able to identify solid invasive components, and as such can be used to accurately locally stage malignant variants.

Treatment and prognosis

Mature ovarian teratomas are slow-growing (1-2 mm a year) and, therefore, some advocate non-surgical management. Larger lesions are often surgically removed. Many recommend annual follow-up for lesions <7 cm to monitor growth, beyond which resection is advised.

Complications

Recognized complications include:

ovarian torsion: ~3-16% of ovarian teratomas, in general: considered the most common complication

rupture: ~1-4%

malignant transformation: ~1-2%, usually into squamous cell carcinoma (adults) or rarely into endodermal sinus tumors (pediatrics)

superimposed infection: 1%

hyperthyroidism (in struma ovarii only)

carcinoid syndrome (rare)

paraneoplastic anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (anti-NMDA receptor) associated limbic encephalitis (uncommon) 8

gliomatosis peritonei: is a rare condition characterized by metastatic glial tissue on the peritoneum, omentum and lymph nodes

Differential diagnosis

General differential imaging considerations include:

-

a high T1 signal that does not suppress with fat saturation

-

pedunculated lipoleiomyoma of the uterus

can be traced back to the uterus

-

ovarian serous or mucinous cystadenoma/cystadenocarcinoma

this is usually only a serious consideration if typical features of mature cystic teratoma are absent (i.e. fat is absent)

tend to occur in an older age group than dermoid cysts

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.